A mix of confusion and frustration swam through her mind as Samone Senevoravong sat in the middle of an outlet mall in Annapolis, Maryland, waiting for her boyfriend and children to finish shopping without her.

Senevoravong had been waiting months for this family vacation, looking forward to eating fresh crabs and enjoying her favorite pastime at Saks Off Fifth and Neiman Marcus — stores they didn’t have in Cleveland, Ohio, where she lived. As she sat in excruciating pain that kept her from even walking around the mall, Senevoravong wondered if she had eaten something bad the day before or pushed herself too hard in a workout.

At no point did she consider the purple caplets of the dietary supplement OxyElite Pro she had begun taking two months before.

__________

What Senevoravong and many other consumers don’t know, however, is that unlike prescription medications, the FDA does not test the dietary supplements sold at GNC, CVS, Whole Foods, Target and on the internet.

Under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA), dietary supplement producers only have to notify the FDA if they are using “new ingredients,” or those not used in dietary supplements before 1994.

The FDA only steps in to remove harmful products from the market after consumers report adverse events. Such events can range from minor discomfort like stomach aches and rashes, to hospitalization and organ failure in extreme cases.

DHSEA also prevents the FDA from regulating the information printed on dietary supplement labels before the products are sold.

Steven Novella, a medical doctor and neurology professor at Yale School of Medicine and editor of the website Science Based Medicine, said these lax regulations allow companies to make “pseudo health claims” for supplements without any scientific evidence.

“We’re back to the age of patent snake oil medicines,” Novella said.

“We’re back to the age of patent snake oil medicines.”

– Dr. Steven Novella

Dietary supplement use in the United States

While dietary supplements originated in the United States in the 1930s and ’40s, these products were intended as a means of addressing nutrient deficiencies in particular populations, such as sailors who did not have access to fruits and vegetables, Erin Brodwin wrote in a November 2017 Business Insider article.

Over the last 50 years, dietary supplement usage has increased as these products became a method of self-improvement and most recently self-care. Dietary supplement usage in the United States has more than doubled since the 1970s, according to the most recent data on long-term trends in Nutrition Journal.

As of 2015, “about half of U.S. adults used at least one dietary supplement in the past month,” and “out-of-pocket expenditures on these products is estimated to be about a third of what people spend on prescription drugs,” Ariana Eunjung Cha wrote in a October 2015 Washington Post article.

Dietary supplement use is common among all age groups, according to data from the Council for Responsible Nutrition, a dietary supplement advocacy group.

A Pepp Post survey of 53 Pepperdine University students found that 75% have purchased a dietary supplement or vitamin in the last year, with 47% agreeing or completely agreeing that dietary supplements are important for a healthy lifestyle. Of this group, 62% disagreed or completely disagreed with the idea that dietary supplements can be dangerous.

Senevoravong chose the dietary supplement OxyElite Pro based on the recommendation of her workout buddy, who promised increased energy and reduced appetite.

As the pain she felt in the mall eventually passed, Senevoravong shrugged it off. At 33, the single mother regularly exercised and ate healthfully, so she didn’t think anything serious could be wrong with her. She certainly didn’t worry that the “natural” diet product she had purchased from a reputable retailer was actually filled with unapproved and fraudulently-used chemical extracts, according to a federal indictment.

Current issues

Unfortunately for Senevoravong, dietary supplement regulation is vastly different from that of prescription medication or even over the counter drugs, said Sunnie DeLano, a registered dietician and Pepperdine nutritional science professor.

While producers are required to notify the FDA of any ingredients which were not in use before DSHEA was enacted, the FDA does not test supplements to see if ingredients match those listed on the label or whether the supplement has potential interactions with prescription drugs, Brodwin wrote.

Additionally, the FDA does not check dietary supplements for contaminants or impurities, which can include lead, mercury, or other vitamins and minerals not listed as ingredients, and in some cases prescription medications, Brodwin wrote.

The FDA currently only has “post-marketing surveillance” abilities, said Edwin Ramos, director of Regulatory Compliance at the FDA. Since the FDA can only regulate products after they have reached the market, some companies may get away with using unapproved ingredients as long as any negative effects go unreported.

“There is no ‘magic number’ of complaints or events that triggers FDA scrutiny,” Lindsay Haake, FDA health communication specialist, wrote. “In some cases, one adequately concerning report can be enough to prompt further investigation; in other cases, it may take multiple data points before a connection begins to appear.”

There could be thousands of adverse impacts before the FDA takes action, said Carol Haggans, a registered dietitian and scientific and health communications consultant in the Office of Dietary Supplements at the National Institutes of Health. One problem the FDA faces is proving cause and effect. Each adverse event report could be attributed to multiple issues outside of the dietary supplement itself.

“[You] need to look at the larger trends and aggregate of adverse event reports to see if there is truly a problem with the supplement that needs to be investigated,” Haggans said.

Regulation and enforcement

Even when there are adverse effects, enforcement may be an issue, Ramos and others said.

When Congress passed DSHEA, the dietary supplement market was significantly smaller. In 1994, “600 supplement companies were producing about 4,000 products for a total revenue of about $4 billion. Today, close to 6,000 companies pump out about 75,000 products,” Brodwin wrote.

The FDA has only 26 people and a budget of $5 billion to regulate those 75,000 products, Brodwin wrote. This gap will only continue to increase in the coming years, according to Statista data from business consulting firm Grand View Research.

Without more resources, Ramos is forced to pick and choose which companies his regulators can succeed in bringing to heel.

“My time is valuable,” Ramos said. “I go for those products that cure AIDS, cancer, diabetes, COVID-19, flu, … the ones that are going to be really critical.”

When the FDA sees a pattern of adverse event reports, Ramos said, it issues a warning letter to the company and publishes this letter on the FDA website. The FDA issues on average 80 warning letters per year.

Some 80% of companies respond right away, fixing mislabeled products, meeting with FDA agents or hiring consultants to bring their products or manufacturing into compliance with FDA regulations, Ramos said.

FDA agents then re-inspect facilities or products. For companies who comply, the FDA issues a warning letter closeout, a document publicly stating that the dietary supplement producer is back in the FDA’s good graces, Ramos said.

For those companies who refuse to comply, however, the FDA can take “enforcement actions,” including recalls or seizures of products and funds. The FDA can also create “consent degrees,” which are legal agreements that list actions the company pledges to take to bring its product into compliance with FDA regulations. Such actions can include sterilizing machines between supplement batches or removing banned ingredients from product formulations.

For particularly egregious behaviors, the FDA can escalate its regulation and secure injunctions, judicial orders that prevent producers from making or selling supplements.

“The FDA only moves for more public actions when the situation necessitates it,” FDA spokesperson Nathan Arnold wrote in an email. “Injunctions are a step that typically occurs when a firm has a history of violations, and has promised correction in the past, but has not made the corrections.”

Both seizures and injunctions are rare due to the limited resources, Ramos said. Although most firms want to do the “right thing,” some companies need extensive handholding to ensure compliance, Ramos said, a luxury the FDA lacks the resources to provide.

__________

A week after her visit to the mall, Senevoravong again exhibited unexplainable symptoms. Running around a local park with her friend, Senevoravong suddenly felt the need to go to the bathroom; in her embarrassed shock, she felt like she needed to vomit, urinate and have diarrhea simultaneously. She began having hot flashes and sweating profusely.

After leaving the restroom, she went home to rest. As the pain faded, Senevoravong let the incident fall to the back of her mind, focusing on the daily grind of parenting and work.

Another week passed before Senevoravong’s coworkers at a market research firm began voicing concerns.

“You don’t look good. You look yellow,” they pointed out.

“I’m fine,” Senevoravong replied, but she made a doctor’s appointment for the next Tuesday just to be safe.

“You look like you’re about to die TODAY,” they urged.

Senevoravong demurred and finished her Thursday at work.

Later that day, the workout buddy who had initially proffered the OxyElite Pro also told Senevoravong she looked yellow. Senevoravong called another friend, a nurse, who immediately knew Senevoravong was in danger and rushed her to the ER.

It was the first of three hospitals she would visit before doctors discovered the true cause of her illness.

__________

Negative impacts of dietary supplements

Senevoravong’s visit to the ER is unfortunately not uncommon.

At least 23,000 people per year are admitted to emergency rooms suffering from “heart palpitations, chest pain, choking or other problems after ingesting dietary supplements,” according to a 2015 New England Journal of Medicine study.

Read more here on how consumers can protect themselves.

While some emergency room visits involved elderly and juvenile patients choking on dietary supplements, the majority was made up of young adults admitted for non-choking conditions. About 2,000 of these visits resulted in longer hospitalizations, many with cardiac symptoms similar to those seen with caffeine overdoses. These symptoms may be attributed to the weight loss and energy supplements often used by adults in the 20 to 34-year-old range, Cha wrote.

Dietary supplements that are contaminated with prescription drugs or dangerous chemicals, those with untested ingredients, or those with abnormally large doses of otherwise safe ingredients can all cause adverse effects.

Drug interactions

While many consumers may not experience adverse effects from dietary supplements, they may be lessening the effectiveness of their other medications, including birth control, antibiotics and antiretroviral drugs for the treatment of HIV.

Drug interactions, or changes in the effectiveness or actions of prescription drugs, are common when combined with herbal remedies, Haggans said. For example, even at standard doses, Vitamin K can interact with blood thinners, preventing them from working properly.

Additionally, Vitamin B6 can interact with Advil, Motrin, and medications prescribed for anxiety or Alzheimer’s disease, and can cause blood pressure to decrease dramatically, Brodwin wrote.

Vitamin overdose

In addition to drug interactions, the lack of consistency in labeling and the FDA’s inability to impose clear requirements on measurements and daily allowances can put consumers at risk for vitamin overdose, Novella said. Even if supplements are labeled, consumers may not bother to read, or may not be unable to understand, the daily allowance percentages and dosages.

The doses of active ingredients in dietary supplements can vary widely, with one tablet of Vitamin C by one brand equivalent to five of another, Brodwin wrote. This makes it difficult for consumers to ingest the correct dose and for medical professionals to diagnose adverse effects in dietary supplement consumers.

Novella agreed that the lack of standardization among brands and products can be problematic and adds that some supplements are simply too high of a dose to be safe.

“The product Airborne, which is just a bunch of vitamins, right?” Novella said. “I mean, it’s not gonna keep you from getting a cold on a plane, but if you take as directed, you actually get an overdose of Vitamin A. … It’ll kill you.”

Increase susceptibility to/exacerbate certain conditions

Probably the most surprising fact about dietary supplements is that rather than preventing long-term health problems and increasing one’s longevity, as many consumers believe, supplements can actually exacerbate certain conditions or increase users’ susceptibility to certain illnesses.

At the 2015 American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting, Tim Byers, a medical doctor from the University of Colorado Cancer Center, shared a meta-analysis of 300,000 patients and 20 years of data, which found that dietary supplements with more than the recommended daily amount of certain vitamins can lead to increased risk for certain cancers.

For instance, increased ingestion of beta-carotene, often associated with improved immunity and long-term vision, can result in a 20% increased risk for lung cancer and heart disease, Byers wrote.

Additionally, increased consumption of Vitamin E can increase the risk of prostate cancer in men, while too much folic acid can increase the risk of developing breast cancer and colon polyps in other patients, Byers wrote.

Contamination

As Senevoravong and many others have discovered, sometimes supplements can be contaminated with unknown or banned ingredients, or even prescription medications or steroids, Brodwin wrote.

This was the case with OxyElite Pro, the supplement Senevoravong took. In 2015, the U.S. filed criminal charges against USPLabs, the Texas dietary supplement producer of weight loss and muscle building products “Jack3d” and “OxyElite Pro.” According to the indictment, the supplements contained synthetic DMAA, a stimulant manufactured in China but banned in the United States because it had been linked to strokes, heart failure and sudden death.

In the indictment, the U.S. alleged USPLabs had Chinese manufacturers create fraudulent certificates of analysis stating the synthetic chemicals they were importing were actually a natural plant-based extract or “geranium flower powder.”

Additionally, the indictment alleged that after the FDA issued a 2012 warning letter about the company’s products being adulterated and having adverse effects, the producers switched from DMAA to new chemicals, aegeline and cynanchum auriculatum. At no point did USPLabs conduct clinical tests of these new ingredients or submit them to the FDA for new ingredient approval as required under DSHEA.

“If I wanted to kill myself, then I would have took street drugs. I don’t do street drugs because I want to remain healthy.”

– Samone Senevoravong

In 2013, following the addition of these two chemicals to OxyElite Pro, several consumers developed jaundice and other liver-related symptoms, with several needing life-saving liver transplants as a result of using the product, according to the indictment.

In Hawaii, more than 40 people were hospitalized after taking OxyElite Pro, Julia Belluz wrote in a 2015 Vox article. Some had acute liver failure and hepatitis, and two needed liver transplants, Andrew Zaleski wrote in an October 2019 Medium article. Anne Andrews, the attorney representing several of the Hawaiian victims, did not respond to requests for interviews.

The two supplements netted the company $400 million in sales between 2008 and 2013, Belluz wrote.

As of 2019, five executives of USPLabs and Sk Laboratories, which helped produce the supplements, pled guilty to multiple felonies, including “introducing misbranded food into interstate commerce with the intent to defraud or mislead,” Josh Long wrote in a March 2019 Natural Products Insider article. Sentencing is scheduled for 2020, Zaleski wrote.

USPLabs did not respond to multiple emails and phone calls requesting comment.

GNC, where Senevoravong and others purchased the supplement, also agreed to pay $2.25 million to avoid federal prosecution for selling OxyElite Pro after the recall, according to a United States Department of Justice statement.

GNC did not respond to multiple emails and phone calls for comment.

USPLabs isn’t alone in producing contaminated supplements.

In fact, other dietary supplements, especially those meant to treat sexual dysfunction, are often contaminated by actual prescription medications (including Viagra) or banned drugs, Brodwin wrote.

Of the 274 supplements the FDA recalled between 2009 and 2012, all of them contained banned drugs, Brodwin wrote. Even after the FDA issued recalls for these supplements, many were still being sold.

Overarching problems

As Senevoravong lay in a hospital bed, yellow with jaundice, she stopped mentioning the OxyElite Pro after the first doctor she mentioned it to appeared unconcerned.

“I never mentioned it because it’s nothing to be concerned about, right?” Senevoravong said. “I mean, it’s a dietary supplement; they treat it as food. It doesn’t have to be FDA approved because it’s not medication.”

As her jaundice continued to worsen, Senevoravong was transferred to two other hospitals. It was at the third hospital that doctors told Senevoravong her gallbladder would need to be removed.

It wasn’t until the night before her surgery that Senevoravong met with a new liver specialist.

“He came to my side and he asked me all the questions,” Senevoravong said. “And he said, ‘Name everything you ate in the last week. Anything that you put in your body, name them all.’ He literally took the time. He said, ‘I want to know everything that went through your body in the last week or two.’”

Senevoravong decided to bring up the dietary supplement again since he had asked her to list everything she had ingested.

“Right when I said it, he started Googling it,” Senevoravong said. “And right when he Googled it, he found that two days ago somebody had liver damage from it, so it was on the web that somebody in Hawaii had liver damage.”

__________

Senevoravong’s case demonstrates one of the overarching issues with the lack of presale regulation of dietary supplements: It leaves medical professionals as well as consumers unaware of potential side effects and interactions.

The FDA’s current lack of regulatory authority further allows supplement retailers to escape culpability for the products they sell, Natasha Singer and Peter Lattman wrote in a March 2013 New York Times article. For example, if the supplements sold at GNC are contaminated, the producer is held responsible, not the retailer.

It’s unclear whether retailers vet the products they sell.

Theresa Kroog, product information specialist at The Vitamin Shoppe, wrote in an email that although the company thoroughly vets its own brand-named products, she could not speak to the quality of the other brands carried in the store.

GNC, Target, CVS, Walgreens and Lloyd’s Pharmacy did not respond to multiple emails and phone calls for comment on how they vet products.

Reasons for FDA limitations

Senevoravong was surprised to find out how little power the FDA has to prevent dangerous products from hitting the shelves or to remove them once they are discovered.

In 1990, Congress passed the Nutrition and Education Labeling Act, which was meant to give the FDA the power to restrict the sale of dietary supplements whose health claims were unsupported by “significant scientific agreement,” whether written on the label or implied by the product’s brand name, Bruce Silverglade wrote in “The Vitamin Wars – Marketing, Lobbying, and the Consumer.”

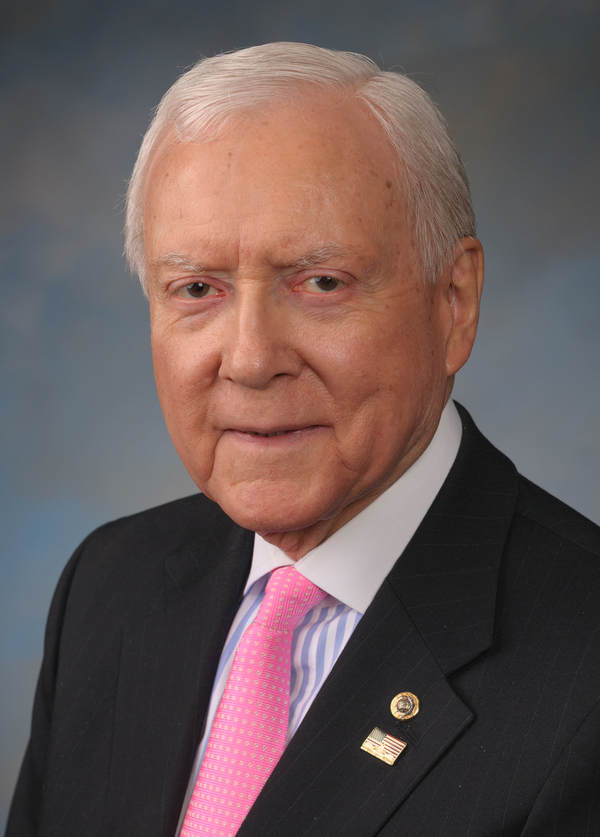

Before the restrictions could be enacted, however, the dietary supplement industry, led by Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch, began actively lobbying Congress for exceptions. Hatch, who represented Utah, where many dietary supplement producers are headquartered, “accepted hundreds of thousands of dollars in campaign contributions from the industry and repeatedly intervened in Washington to quash proposed legislation that would toughen the rules,” Anahad O’Connor wrote in a 2015 New York Times article.

Hatch and the other pro supplement politicians engaged in a propaganda war against the FDA, telling consumers and natural health retailers the government agency was trying to eliminate all sales of dietary supplements, Silverglade wrote.

Congress received hundreds of thousands of calls and letters from concerned customers, and more than half of Congress eventually cosigned DSHEA, Silverglade wrote.

Calls to Orrin G. Hatch, his son Scott Hatch, the lobbying firm of Walker, Martin & Hatch, and to the pro-supplement lobbying groups the Alliance for Natural Health and the Consumer Healthcare Products Association, all went unreturned.

Critics of DHSEA argued that the dietary supplement industry lobbying created a scenario where producers can act without impunity.

“So, what this does is it sets up supplements to really have a kind of ‘I’m gonna do this ‘til I get caught’ type of scenario,” DeLano said.

Current regulation also creates few barriers for new producers.

“You could create a supplement factory in your garage,” DeLano said. “You could make a supplement, put whatever you want in it, sell it on the internet, and the only way that it’s gonna get pulled is if someone reports that they had a side effect from it.”

People took advantage of the lax regulation to make a lot of money, DeLano said.

“These rules [DSHEA] were written by the dietary supplement industry, and they still keep violating them,” Novella said.

__________

Senevoravong’s doctor immediately reached out to the doctor treating the Hawaiian patients and confirmed they too had taken OxyElite Pro.

After a week and a half in the hospital and legions of tests, including a liver biopsy, Senevoravong received news that she would not need a liver transplant or a gallbladder removal; however, her way of life would never be the same. The inflammation in her liver was reversible, but she would need to limit her consumption of certain foods and alcohol and be vigilant about medications and dietary supplements which could have deleterious impacts on her liver.

“They put me on prednisone, but there was nothing really they could do for me or give me. … My liver has just got to, I guess, you know, regenerate itself,” she said.

__________

Advocates for dietary supplements

Advocates for dietary supplements argued that vitamins and minerals created following good manufacturing principles are safe and effective.

“Dietary supplements can address issues in a way that lifestyle sometimes is unable to or can augment or target certain issues that somebody might be experiencing,” said Lise Alschuler, naturopathic doctor and professor of Clinical Medicine at the University of Arizona Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine.

Alschuler explained that there is actually a large body of research on various dietary supplement ingredients that demonstrate effectiveness and safety, but that most of that research is being conducted outside of the United States.

“In the United States, it costs millions of dollars typically to research something from start to the end,” Alschuler said. “And with a dietary supplement, if I were to do a clinical trial on the use of Zinc to prevent common colds and my trial was successful, there’s no way for me to reap any kind of benefit from that trial financially because I can’t patent zinc.”

Even with the lack of clinical research, however, Alschuler said the current regulations are enough to protect consumers of dietary supplements.

“The strengths of DHSEA are that they set forth very clear requirements for how dietary supplements need to be manufactured and marketed in the U.S.,” Alschuler said. “When companies follow those regulations, they produce excellent quality, very reliable supplements.”

While there may be some unscrupulous actors, Alschuler said most companies want to comply with FDA regulations.

“As an industry, it’s in their best interests to be a safe industry and to gain public trust,” Alschuler said.

Scott Watkins, salesperson for Shaklee, a direct to consumer vitamin and dietary supplement company, said consumers should research the history of supplement producers as well as their track record of adverse event reports, which can be found through FDA CAERS (Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) Adverse Event Reporting System).

Watkins explained that reputable companies like Shaklee actually adhere to standards higher than those recommended by the FDA and that customers willing to pay for higher quality supplements can find trustworthy companies.

“The dietary supplement industry as a whole engages in a lot of self-policing efforts to identify bad actors,” Alschuler said.

Alschuler identified the Council for Responsible Nutrition and the Natural Products Association as industry watchdogs. CRN and NPA did not respond to multiple emails and phone calls for comment.

Needed changes

FDA officials hope to institute product listing requirements for dietary supplements and vitamins to better protect consumers.

“To be able to make those choices with respect to dietary supplements, consumers need to have access to safe, well-manufactured, and appropriately labeled products,” FDA spokesperson Haake wrote.

Having basic information about each product, including its name, ingredients and product label, would allow the FDA to prioritize how it uses its resources, enabling it to take “more effective, risk-based enforcement actions,” FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, a medical doctor, said in a February 2019 statement.

“One of our top goals is ensuring that we achieve the right balance between preserving consumers’ access to lawful supplements, while still upholding our solemn obligation to protect the public from unsafe and unlawful products, and holding accountable those actors who are unable or unwilling to comply with the requirements of the law,” Haake wrote.

Alschuler said the FDA needs more resources to achieve these goals, since the agency currently does not have enough employees to audit every company. Melissa Halas, registered dietician and media representative for the California Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, also advocated for increased government funding for clinical research of dietary supplements.

The advocacy group Alliance for a Stronger FDA also promotes increased funding for the FDA, according to a group representative.

Others think that the FDA should have the power to approve dietary supplements before they reach the market and to bring more substantial criminal and civil charges against unethical dietary supplement producers.

Anti-supplement advocates like Novella said DSHEA needs to be completely removed and the whole regulatory system redone.

“Australia and Canada have better regulation than we do. … Our system is set up to benefit the [dietary supplement] industry,” Novella said.

Some states have begun more closely regulating dietary supplements within their borders, including New York, which began DNA barcoding (or genetic testing) of dietary supplements to make sure what was listed on the label was actually in the jar. This testing resulted in major lawsuits against Target, GNC, Walgreens and Walmart, Long wrote.

“It’s naive to think it [the dietary supplement industry] will self-regulate; poor people will die; rich people will prosper.”

– Melissa Halas

California also has specific regulations for dietary supplements, including that all businesses which manufacture or distribute dietary supplements formally register with the California Department of Public Health in the Processed Food Registration (PFR) program prior to operating, wrote Ronald Owens, media relations representative for the department.

Novella recommended consumers advocate for enhanced regulation within their own states in addition to pressuring the FDA and Congress for stricter national policies.

“It’s naive to think [the dietary supplement industry] will self-regulate,” Halas said. “Poor people will die; rich people will prosper.”

__________

“I think they’re worse than drug dealers because they’re making so much money off of this, and on top of it they’re lying and saying that it’s good for you. You know, if drug dealers are going to jail for 20, 25 years, why not them?”

– Samone Senevoravong

Although Senevoravong was lucky enough to survive her encounter with tainted dietary supplements, she is still on the liver transplant list just in case.

She still wonders how the deadly, untested ingredients got into her pills anyway.

“I don’t know why the FDA doesn’t approve it,” Senevoravong said. “They shouldn’t be able to sell it over the counter like that. It’s like, if I wanted to kill myself, then I would have took street drugs. I don’t do street drugs because I want to remain healthy.”

Zaleski reported that the makers of OxyElite Pro may serve anywhere from three to six years in prison. Senevoravong thinks that’s not enough.

“I think they’re worse than drug dealers,” Senevoravong said. “Because they’re making so much money off of this, and on top of it, they’re lying and saying that it’s good for you. You know, if drug dealers are going to jail for 20, 25 years, why not them?

Yasmin Kazeminy completed the reporting and writing for this story under the supervision of Dr. Christina Littlefield in Jour 590 in Spring 2020.