Smart. Silent. Submissive.

These are just a few of the stereotypes individuals promulgate about the Asian American community at Pepperdine.

A Pepp Post poll of 51 Asian-American students at Pepperdine found that 70 percent of Asian Americans feel a cultural divide between Asian Americans and the white community. The poll included students of Filipino, Taiwanese, Korean, Chinese and Japanese descent. Interviews show Asian Americans feel stereotyped as so-called model minorities.

“It’s insidious —this part of the stereotype being quiet and submissive,” Sociology Professor Rebecca Kim said. “That you are going to be collegial and accommodate to white culture instead of speaking up saying and saying ‘what about our rights?’”

Asian Americans make up 11 percent of the undergraduate population at Pepperdine. Whites dominate the cultural and racial norms. Existing stereotypes, an institutionalized silence among the Asian American community and cultural and generational differences, all create issues that maintain the racial divide between the white majority and Asian-American community.

Lack of identity in the Asian-American community

Rebecca Kim said Asian-American students’ lack of involvement in politics on campus reveals the silence that is characteristic of the Asian-American community.

Rebecca Kim, who is Korean American, is currently co-authoring a book on Asian-American and African-American religious leadership styles.

“When Pepperdine had its ‘Black Lives Matter’ protest, I noted very clearly that no Asian Americans or Asians showed up,” Rebecca Kim said. “So I talked with the dean and asked ‘Why do you think Asian Americans aren’t present?’ to which she said ‘They have yet failed to articulate their voice.’”

Rebecca Kim said this captured a lot and made clear that part of being Asian American at Pepperdine is general silence. This general silence creates a lack of identity for the Asian-American community.

This silence has also bred a reality where the white majority is unaware of the racial divide that exists between the Asian-American minority and the white majority.

Susan Bousman, director of Student Activities at Pepperdine, said she was caught off guard by questions about the divide as she wasn’t aware that there was any sort of tension present.

“It’s funny because there’s so much more focus on black and white tension,” Bousman said. “There’s barely any attention put on Asian American-white tension which is why I was caught off guard a little.”

Stereotypes and obstacles Asian Americans face at Pepperdine

Additionally, there is an even split within the Asian American community, as roughly 47 percent of Asian American students said they have experienced more racism at Pepperdine than where they grew up while roughly 47 percent said they experienced less.

The poll also revealed that 45 percent of Asian Americans tend to mostly hang out with other Asians and 35 percent mostly hang out with mixed ethnicities.

Echo Zn, a senior business administration major and a Chinese American, said she was often dismissed and ignored in the class setting because of her ethnicity.

“In group chats for group projects, whenever I suggested something or asked to meet up, no one ever responded — only for me,” Zn said.

Other students said the stereotypes they know to exist have left them feeling dismissed by the majority population and has impacted their decisions.

Katie Kawachi, a senior political science major, said that when she first came to Pepperdine, she struggled with combatting stereotypes she knew were put on her because she was Asian American.

“The reason why I didn’t want to hang out with other Asians my freshman year was because I didn’t want to be the stereotypical little Asian girl who only hangs out with other Asians,” said Kawachi, who is Filipino, Japanese and Chinese.

Korean American Gina Myung, a senior public relations major, said observing responses to international students makes her fearful of what others assume of her before she is able to get to know them.

‘When a loud, large group of Asian people walk by, people will look toward them as ‘there goes the international kids’ and it’s not a positive response,” Gina Kim said. “And I guess knowing this, it makes me think about how other people are judging me based on how I look just based off Asian stereotypes.”

Myung also added that there are microaggressions that take place on a daily basis, even in the classroom setting.

“There are so many times where even my professors asked if I could speak English and assumed I was an international student,” Myung said.

How the white norm cultivates silence

Rebecca Kim said the model minority myth put upon the Asian-American population plays a huge factor in why the Asian American community doesn’t speak up.

“Asian Americans are stuck in the limbo between the white-and-black divide,” Rebecca Kim said. “They are categorized as the model minority because they’re not contentious with the white majority.”

Whites first coined the term model minority to describe the Japanese Americans who had succeeded in society even in spite of the Japanese internment and alienation they underwent, Rebecca Kim said.

Model minority is also used to indicate the reason for Asian American success is because they are submissive and assimilate easily to the white majority, Kat Chow reported in an April 2017 National Public Radio podcast.

David Humphrey, dean of Student Affairs, Diversity and Inclusion at Pepperdine, said the model minority myth is problematic because it fails to account for real issues present within the Asian American community.

“It gives us the ability to generalize things across a large, very diverse group of people when there are unique issues to each subgroup of a population,” Humphrey said.

Rebecca Kim added that Asian Americans feel less motivated in speaking up about racial issues because of this notion of the model minority.

“I figured out that Asian Americans are pretty rational about racial order,” Rebecca Kim said. “They know they haven’t been the ‘bad’ minority because they don’t speak up against the white majority.”

Mina Kim, senior public relations major, agreed.

“Even if someone says something offensive, I don’t speak up,” Mina Kim, a Korean American, said. “It’s easier not to have to create that awkward tension in a conversation when someone says something somewhat offensive or insensitive to you.”

Rebecca Kim adds that in the few cases where Asian Americans have voiced their opinions on frustrations in the racial divide, they faced major backlash from both the Asian-American community and the white community.

“There is a lot of racial pushback from the white community because the reason why we were allowed to succeed was mainly because we were submissive,” Rebecca Kim said. “Then we also receive pushback from the Asian American community for speaking up instead of enduring for the whole group.”

How Asian culture cultivates silence

Asian culture is deeply seeded in a collectivist mindset that originates from ancient ideologies and sayings such as the Confucian ideal that “the nail that sticks out gets hammered,” Marcia Cartaret wrote in an April 2013 Dimensions of Culture article.

In other words, it’s normal and almost expected of Asian Americans to sacrifice their voice and opinions if it means overall progress for the group.

Rebecca Kim said that because of the culture she grew up in, it influenced her decisions in speaking up.

“Because my Asian American background values harmony and maintaining peace, it wasn’t and isn’t all that difficult for me to hold my tongue in a group setting when someone says something uncomfortable to me,” Rebecca Kim said.

Additionally, senior law major Philip Cai said culture is nuanced with each generation. First generation Asian Americans will experience different cultural differences than second generation and first generation international students and so on and so forth.

Cai said as a second generation Chinese American, his culture is focused primarily on succeeding and doing well in academics because of the obstacles his parents had to overcome.

“Before Pepperdine, so much of my life was focused around academics because my parents went through the American dream and worked really hard, so there’s a high pressure to succeed,” Cai said. “So all my relationships were built around trying to succeed together in class. When I came to Pepperdine, I wasn’t really used to the relaxed attitude that my white friends had at first.”

Furthermore, Rebecca Kim said the Christian aspect of Pepperdine adds another layer to this silence.

“Being a conservative Christian campus, it doesn’t make it easier because if you’re a Asian American Christian, you just want to get along,” Rebecca Kim said.

Creating a Solution: Awareness out and within

Rebecca Kim said the first step in resolving the racial divide is simple: proving that this racial divide exists by speaking up and calling it out.

“First, we need to articulate the problem,” Rebecca Kim said. “Articulating the problem — that’s huge. I don’t think that whites know that this is happening. Being viewed as submissive, the position we are put in, the frustration.”

Kawachi agreed and said there must be mutual effort from both the minority and majority group to engage in dialogue.

“I think it’s an even two-way street,” Kawachi said. “They have to want to listen.”

Cai said both groups need to break past their comfort zones and learn to accept other points of view.

“Both sides need to make an effort to understand people from different backgrounds and try to see other perspectives and also try to hang out with people that aren’t the same color as you,” Cai said.

Rebecca Kim said the next step is for Asian Americans to become self aware of the background and culture they come from and reconcile that with choosing to speak up and use their voice.

“Awareness helps a lot,” Rebecca Kim said. “Where do you come from, your background, culture that makes you not want to speak up? But also recognizing that because you are silenced, you need to speak up.”

Humphrey said Pepperdine has been and is currently working to create an environment that feels inclusive and safe for every ethnicity on campus.

“My goal is to help continue to create a space that is culturally responsive, sustained and inclusive to communities of color,” Humphrey said.

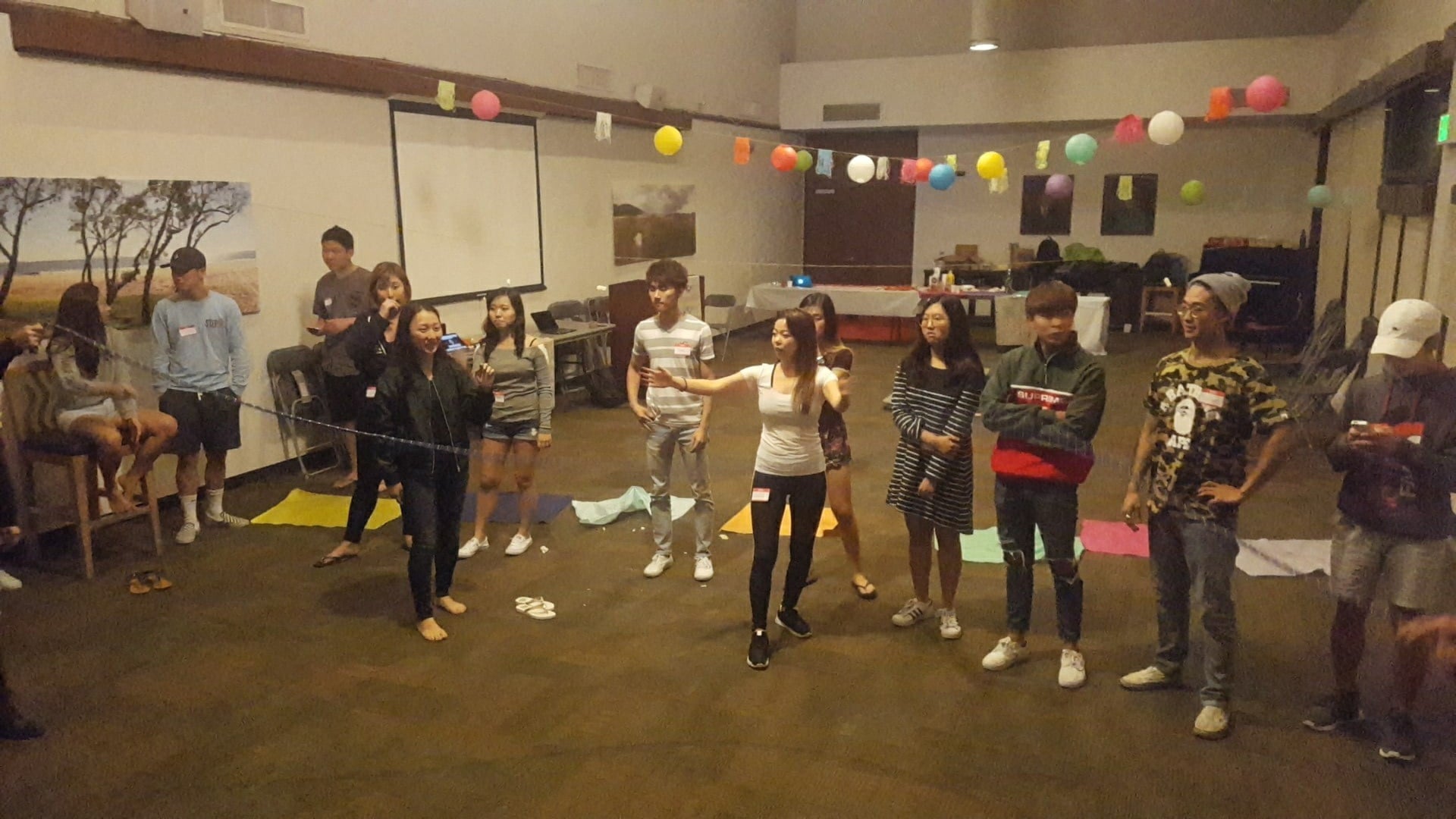

Pepperdine’s cultural clubs play a role in educating and sharing their respective cultures.

Myung, Kawachi and Zn are all leaders in Korean Student Association, Filipino Student Association and Chinese Student Association respectively.

Kawachi said Pepperdine is working very hard to make sure that cultural clubs are truly using their voice authentically.

“For our Filipino Club, Intercultural Club Council will always make sure that the image that is put out for our culture through our club is authentic and true and they really devote themselves to making sure they get it right and I think that’s awesome,” Kawachi said.

Kawachi said that being part of FSA has allowed her to feel supported and connected to those who share the same cultural values as her.

“I’m Catholic and a lot of Filipino students in the club are also Catholic and I think that just being surrounded by others who look like you and who understand your culture is nice,” Kawachi said.

April Chung completed the reporting for this story under the supervision of Dr. Christina Littlefield and Dr. Theresa de los Santos in Jour 241 in fall 2017. Dr. Littlefield supervised the writing of the web story.