A priest.

Or a doctor.

Salvador Hernandez did not know which one he wanted to be. All he knew was that he wanted to help others. His passion for studying medicine was strong, just like his faith.

So, he left it up to God.

“I struggled with many things, but God was always there,” Hernandez said. “Reading scripture and praying always got me an answer by being straightforward with God. So, I said, ‘God, if I’m supposed to be a priest, don’t let me into med school.’ ”

The decision was harder because he was surrounded by religious figures at church and at home – his uncle is a priest, and his family is all religious. But he also craved the economic stability that would come with being a doctor and the ability to travel on medical mission trips.

“I needed to listen to what he was telling me,” Hernandez said. “Was it me wanting to choose a path or me listening to what he called upon me? My father was the most devout, but he wholeheartedly supported me September to March of 2009 as I waited to see what he (God) wanted of me in regard to school.”

He got into the University of Guadalajara. And he took it as a sign from God. The road to becoming a doctor, however, was a complicated path.

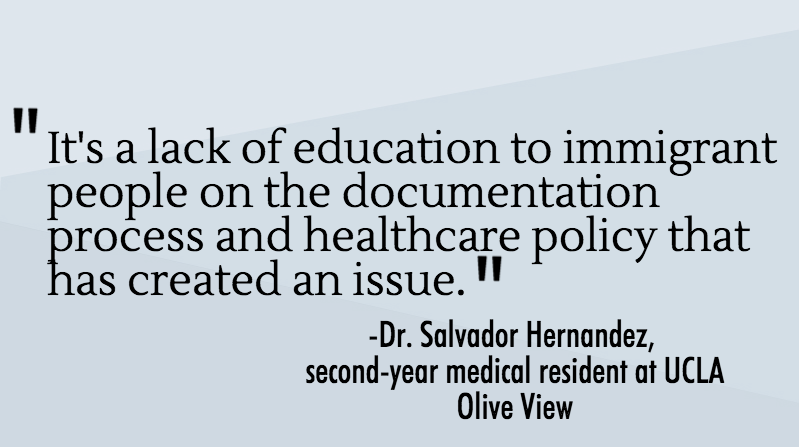

Hernandez, now 32 and a second-year medical resident at University of California, Los Angeles Olive View Hospital, said he was fortunate medical school was even an option.

“I grew up with two younger sisters, my dad and mom, and my parents were very advanced in their minds and way of thinking,” Hernandez said. “My dad owned land in Mexico, so, when I was growing up, out of my friends, I was one of the only ones who got to go to school and my family allowed me to attend university.”

His family also had U.S. citizenship. His grandfather had left Mexico to look for work in the U.S., and never came back. His father, also named Salvador Hernandez, followed in his father’s pathway and left young Hernandez and the rest of his family to look for work in California.

***

Hernandez graduated with his medical degree as Doctor of Medicine and Surgery from the University of Guadalajara in 2009. Unbeknownst to him, his own father needed medical attention.

Hernandez was just about to start his medical residency in Guadalajara when he received a worried call from his mother, Rosa Lopez, who was 53 at the time.

It was about his father. The man who had inspired him to help others, who always made him think twice and ask, “What would my dad do in this position?”

***

His dad – then 75 – was sick, very sick. Sick enough to trade his home in Mexico permanently for good health care in the U.S.

It was multiple myeloma, which causes cancer cells to accumulate in the bone marrow, where they crowd out healthy blood cells, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Hernandez said it was common for his father to vacation to Santa Barbara for a yearly physical.

“My dad would say, ‘They treat you like royalty in the hospitals there.’” Hernandez said.

However, one year Hernandez’s father stayed over two weeks and he attributed his extended stay to high cholesterol.

“I wasn’t as emerged in the U.S. medical field at that time, so I didn’t catch the red flag at first,” Hernandez said. “But then I called the clinic and asked for my dad’s records and I found out this way that he had cancer. He had said to the doctors that he didn’t want treatment, and I had to tell my mother.”

In time, Hernandez’s father gave-in to his mother’s pleas and began chemotherapy. For six months, his mother and sisters, Monica, 10, and Rosa,13, stayed in Santa Barbara with the senior Hernandez during treatment.

And then, Hernandez received the call that no child wants to ever endure.

“Salvador, if you do not come to Santa Barbara now, you may not get to say goodbye to your father. He is dying,” his mother told him.

He spoke with his residency program and decided to take an immediate leave.

“I requested three months time off initially to visit with my dad and before I even left Mexico, I got a call from my mom who said that I needed to drop everything and go,” Hernandez said.

***

The doctors could only help with his father’s pain level and nothing more.

“It was hard,” Hernandez said. “My dad was incubated and it was really painful for him. Intense and hard for all of us. It was hard for him to even hug us, to lift his arm. He passed away four days later.”

Culturally, Hernandez said he quickly learned that the U.S. is very different from Mexico.

“Time is the difference and the biggest challenge,” Hernandez said. “No emergency visa can be generated quicker than three weeks, so no other family members could come to support us or my mother. We are U.S. citizens, so we could stay, but other family from Mexico couldn’t even come to the funeral.”

Hernandez said his mother and sisters became very depressed, and that his mother lost her jobs working in a factory and cleaning houses because she was too depressed to work. He lost his residency spot and moved to San Fernando with a distant uncle to stay close to his mother and sisters who stayed in Santa Barbara.

***

Hernandez has been living in California now for more than six years. He’s had citizenship for 10. But he still best identifies with his Hispanic background.

After his father died and his family decided to relocate permanently to California, he needed money to support his family. Thankfully they were citizens and had access to health insurance, but they still needed income. Hernandez said he would do anything for quick cash in order to support his mother and sisters. He went to clothing stores, restaurants, catering places – anywhere looking for work.

But it was an emotional time, and work was sparse.

It was his continued faith that led him to his own guardian angel.

***

“I’m Catholic and through my church group, I met Jenny,” Hernandez said. “She took me under her wing.”

Jenny Rosales, 75, is a registered nurse working at Olive View who Hernandez said is like a loving grandmother to all those she meets.

“Through Jenny I got connected with Olive View, she connected me to people to interview with, and I quickly learned how important health insurance in the U.S. is,” Hernandez said. “I saw the struggle of my people without insurance at Olive View. You know, the county can only do so much.”

Before meeting Jenny, Hernandez didn’t know much about Chagas, a disease which mainly affects Hispanics. Now, he is one of the main researchers on the disease. Olive View is the main place for Chagas research and treatment in LA, and the hospital opened the first clinic in the U.S. for the diagnosis and treatment of Chagas disease in 2007.

According to the World Health Organization, Chagas is a potentially life-threatening illness caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. It is found mainly in endemic areas of 21 Latin American countries.

Symptoms start mild, including swollen eyelids, fever, enlarged lymph glands and stomach pains or swelling. If the disease goes untreated, the parasites nestle mainly in the heart and digestive muscles, which in later years can lead to sudden death, according to WHO.

“It’s a lack of education to immigrant people on the documentation process and healthcare policy (of immigration) that has created an issue,” Hernandez said.

Since Chagas can be treated if caught in its early stages, Hernandez said Olive View aims to help those who may not even know about the disease.

Hernandez said he saw a patient diagnosed with Chagas who had primary care and was simply looking for someone to help her, so she went to see Hernandez at Olive View.

The woman was a U.S. citizen and Hispanic, like himself. But for more than 11 years she had been looking for someone to help her with her illness. She finally found Hernandez’s team at Olive View and they were able to treat her.

“It’s portrayed as an exotic disease, but I’ve treated over 300 cases of Chagas,” Hernandez said. “It’s a reality here.”

Jalal Dufani, a second-year resident who works with Hernandez at Olive View, said Hernandez is a vital member of the Olive View team due to his understanding of the Latino language and culture.

“He grew up in Mexico so he knows how to deal with the patients,” Dufani said. “All the cardiology department in the hospital loves Salvador, honestly he always has the best relationships with the patients out of us all.”

***

Now Hernandez is in residency at Olive View as an internist and Chagas expert. His family is still located here, throughout California.

Hernandez has a new-found desire to continue onward in his studies to eventually become a cardiologist, which he credits to Dr. Sheba Maynandi, the director of the Chagas program at Olive View. Hernandez said Maynandi donates her time to the Chagas cause, even though she is not of the Hispanic culture and is a full-time cardiologist.

“When I see the huge passion in her for helping poor people not of her country, I want to do more for my own community,” Hernandez said. “Seeing others interested in my original community makes me want to do more too – do more for Chagas and other health needs.”

“She saw a major need within my community and didn’t wait for others to take responsibility – she saw a need to act,” Hernandez continued.“She went ahead and just did it.”

Hernandez wishes that somebody out there had been looking out for his father regardless of his community origin.

“If I can bring people of all backgrounds new happiness through my knowledge, while really learning more through them, then that’s what makes me happy,” Hernandez said, smiling.