Ida B. Wells-Barnett was an African American woman, journalist, abolitionist and feminist who led an anti-lynching crusade in the United States in the 1890s. Wells-Barnett transformed the lives of many African Americans by starting the first African American kindergarten in Chicago and being amongst the original founders of The National Association for the Advancement of Colorful People (NAACP).

Yet only about 14 percent of students surveyed are confident they know who she is.

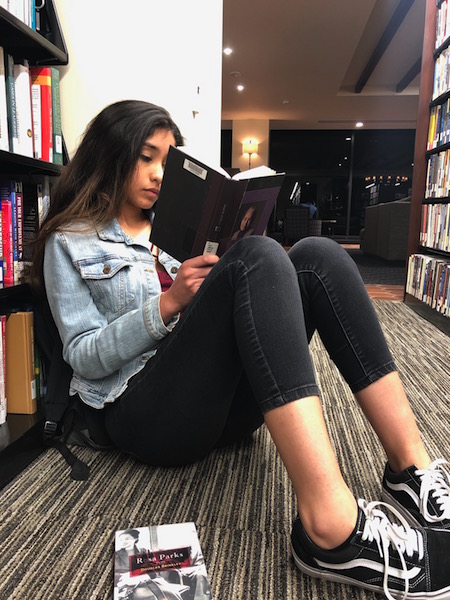

A Pepp Post poll of 56 students found that while many students haven’t heard of women such as media mogul Oprah Winfrey or Civil Rights activist Rosa Parks, about 73 percent of students had no knowledge of a woman named Anna J. Cooper, one of the most prominent scholars of U.S. history known for promoting black liberation and feminism.

“I think it’s important to learn about everyone; I think it creates a better understanding of different people,” junior business major Temuulen Uranbayar said. “It makes it so that anyone can relate and you’re not just learning about these white old dudes.”

The lack of awareness of ethnic female leaders stems mainly from the fact that history and literature classes focus on white males, professors said. Professors are working to bring more diversity into the curriculum.

Ignorance on influential women

The poll surveyed students as to how well they know influential female figures. Only celebrities and Rosa Parks ranked highly.

However, nearly 78 percent of students think it’s important to know about these influential figures and half wished they knew more.

Exactly 55 percent of students believe that in order to advance the equality of women, all college students should be taught about influential women, past or present. Only 5 percent believed that Pepperdine professors were currently doing a quality job of teaching about important female figures in their discipline.

“My classes barely covered minorities and when we did, it was usually for a cultural month like Black History Month,” junior psychology major Victor Haynes said.

Successful film writer and producer Shonda Rhimes is an African American woman who broke through barriers to create one of the most successful medical dramas, “Grey’s Anatomy,” along with other well-known TV shows. Yet, roughly 24 percent of students have never heard of her despite her advancements as a black woman in the television industry.

African American activist Tarana Burke started the “Me Too” movement, which gives voice to individuals who’ve been sexually abused or harassed. Burke encouraged many people to share stories about their sexual abuse to help others affected. About 70 percent of students had no idea who Burke is.

Feminist activist Lucretia Mott advocated for women’s rights and the ending of slavery but only 7.1 percent of students know who she was.

About 4 percent of students know of Phillis Wheatley, the first African American female poet whose legacy proved that blacks could be both intellectual and artistic.

Nora Ephron is known for her successful romantic films, winning Academy Award nominations for best writing three times in her life. About 75 percent of students reported never hearing of Ephron and her impact on the film industry.

Global movement to diversify curriculum

Diversity in curriculum has been a constant and global struggle between universities and students.

When a group of students at the University of Cambridge called for more non-white writers to be included in their English curriculum, there was backlash, Harriet Swain wrote in the 2019 Guardian article, “Students Want Their Curriculum Decolonised. Are Universities Listening?”

“Lola Olufemi, who led the call, became the target of online abuse after one report wrongly suggested it meant replacing white authors with black ones,” Swain wrote.

Administrative leaders make it a point to outline what diversity means as it relates to education.

“This is not just about different ethnic groups but applies to gender, disability, and sexual orientation too,” Swain wrote. “It’s driven not just by universities’ sense of fairness but also by political and legislative pressures.”

Diversity is important in education because it helps to build understanding of various cultures and allows people to make educated opinions and judgements, Mina Huang wrote in the 2015 article “Diversity Matters: The Beauty and Power of Difference.”

English Professor Julie Oni said she makes it a point to have a global perspective when bringing in authors and examples.

Oni brings in influential figures such as Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Jamaican British novelist Zadie Smith and Mexican American poet Jimmy Santiago Baca.

“Every semester, I bring in stories from people all around the world,” Oni said. “My dad is from Nigeria; I’m really interested in a lot of Nigerian stories.”

Junior psychology major Vanessa Orona emphasized that men are viewed as the superior group in society, which results in their contributions superseding those of other influential figures.

“It’s just a reflection of how society is now,” Orona said. “I would like there to be more discussion about minorities because there’s also a big role that we play.”

Professors responsible for diversifying curriculum

Teachers have a particular responsibility to recognize and structure their lessons to reflect student differences, Matthew Lynch wrote in the 2018 article “4 Reasons Why Classrooms Need Diversity Education.” This encourages students to recognize themselves and others as individuals.

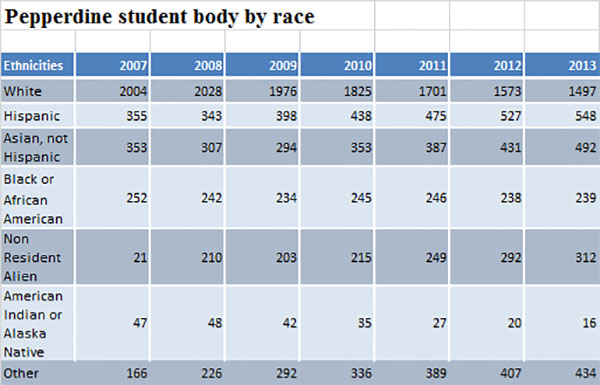

Seaver’s student body population is about 60 percent female and only 40 percent male, according to 2018 fall semester enrollment data from the Office of Institutional Effectiveness. Just over half of the student body is non-white.

Students come from all different backgrounds, which means it’s important for their differences to be understood and respected so that students are taught about what they are interested in, Oni said.

“Even if the student body here is not super diverse, there’s still a lot of interest in young people nowadays with different kind of living and way of life experiences,” Oni said. “We have a responsibility to engage and inspire that in the classroom.”

Female voices should always be an important factor incorporated in curriculum in every classroom, professors said.

“A lot of college classrooms have more female students than males, and if you’re trying to reach students and what their actual identity is, then it only makes sense that you would have half of your readings be from women if that’s who you’re actually speaking to,” Oni said.

Raelene Mendieta, junior sports medicine major, said it’s important for professors to implement more diversity in the curriculum.

“They always say that history repeats itself but obviously we would want it to repeat itself in a better light,” Mendieta said. “If you want women to surmount to the women in the past doing incredible things like starting movements and organizations that are still here today, I think it’s important that females and males today are well aware of what’s happened in the past so we can only benefit from it and have a more balanced society.”

Haynes touched on the importance of incorporating women in history classes.

“I do believe professors should do a better job of talking about influential female figures because they are history,” Haynes said. “If you’re teaching a history class and talk about all the men but not the women, then your history class is biased.”

Pursuing diversity through SEED

Kendra Killpatrick, mathematics professor and senior associate dean of Seaver College, said she was adamant about the importance of diversity in students’ curriculum before and after she became one of the administrators in charge of SEED, which stands for Seeking Educational Equity and Diversity. Killpatrick was in charge of the faculty training program for the last two and a half years before changing positions.

The SEED program assisted Killpatrick in adding more modern-day issues surrounding different ethnic groups in her curriculum.

“Trying to bring in more context about how math can be used in the world in terms of social justice,” Killpatrick said. “And also just to greater awareness of really the whole identity politics going on behind math coming to the forefront.”

Sarah Stone-Watt, divisional dean of Communication, reflected back to how SEED helped her understand the different perspectives students may have.

“It helped me get a better sense of how other people react to it because I think when you teach a topic or read about a topic a lot you tend to think that everyone thinks about it the way that you do,” Stone-Watt said. “What SEED did for me was help me to see the very different ways that people from different disciplines and backgrounds interacted with that content.”

Stone-Watt said the Communication Division has worked to bring in diversity to the classroom.

“The discipline has been working really hard to change whose voices get heard,” Stone-Watt said. “Talking about racial issues, gender issues, class issues; they’re not in the canon, stuff everyone thinks you have to read but they should be, so we’re reshaping that and thinking, ‘How do we put these different perspectives in conversation with one another?’”

English Professor Julie Oni updated her syllabi to include Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (left). History Professor Loretta Hunnicutt includes student learning objectives in syllabi that describe what groups of people will be taught in her History 204 class (right).

History Professor Loretta Hunnicutt said she constantly tries to update her syllabi, especially recently as she has realized that students are hungry to know about how history informs today, which has been a huge focus of hers over the last two years.

“The first thing I do in most classes I teach is say, ‘One of my main goals is to not put white men at the center,’” Hunnicutt said. “And I say, ‘That’s not because I’m trying to tell you they don’t matter — that’s not the point. I’m trying to say that everyone does.’”

Hunnicutt said she was doing what SEED calls professors to do beforehand because history essentially guides in that direction.

“Phillis Wheatley — I definitely talk about her,” Hunnicutt said. “I spend like 10 minutes or 15 even talking about her and Ida B. Wells for sure.”

Professors understand the power dynamic that flows throughout the curriculum as far as who students are being taught about.

“In teaching on powerful people, I am not privileging powerful people,” History Professor Stewart Davenport said. “I’m not saying that their story is the only story; power is unfair.”

Davenport makes a point to discuss a woman by the name of Harriet Beecher Stowe, an American author who wrote “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” which helped fuel abolitionist sentiment toward the Civil War. That work of fiction translated into cultural power, Davenport said.

“I don’t give a lot of attention to literature in my classes,” Davenport said. “Phillis Wheatley had an important voice but it didn’t have as much of an effect on people.”

Challenges to implementing diversity

Communication Professor Robert Ballard has led the SEED program for the last three years. Ballard is knowledgeable about the goal of the program and how it shaped his curriculum personally.

“The challenges come from, historically it’s been predominantly white, predominantly male voices that dominant the research,” Ballard said. “The challenge is always, ‘How do you find the voices that have the weight and the credibility and to be able to talk about that in counterpoint to hundreds of years of writing and research?”

The lack of open-mindedness from faculty raises a challenge in this movement as well, professors said.

“We assume that that’s the one way to think about a concept when in reality there are lots of different roads to a concept,” Stone-Watt said. “I always want to push back against the assumption that there’s only one way that people should know a piece of information or an experience.”

Oni emphasized that modern technology allows students to have access to female stories today that professors didn’t have access to in the past.

“It’s something about these historical women being isolated outside of social media sphere that almost makes them feel more legendary,” Oni said. “It’s like we don’t totally know everything about them because we just get photographs and not their social media posts or whatever we would have today.”

Haynes said he finds it challenging to think beyond who professors taught him to care about to influential individuals he should also be aware of.

“I unnoticeably catch myself being biased and would only talk about male figures or white male figures instead of knowing my own culture,” Haynes said. “Women are very important, and to know what they’ve done in this world is very important as well.”

Tahte’Ana Nelson completed the reporting for this story under the supervision of Dr. Christina Littlefield and Dr. Theresa de los Santos in Jour 241 in Spring 2019. Dr. Littlefield supervised the web story.