It was just a normal day of practice.

Pepperdine’s Men’s Volleyball Team was preparing for the spring 2017 season when junior psychology major Jack Cole jumped up for the ball.

He came down wrong, tearing a ligament in his knee. Just one moment, one wrong move, and he was out for the entire season.

“It was so incredibly frustrating,” Cole said. “I have no words to describe the combination of anger and sadness I felt on a daily basis.”

Athletes like Cole dedicate their life to playing a sport. When athletes are injured, the focus is on recovery, both physically and emotionally. Coaches and trainers help athletes prevent injuries through proper conditioning, but when the inevitable happens, Pepperdine tries to help athletes get back in the game.

Injury prevention

Injuries among college athletes are inevitable.

“If we could prevent injuries before they happened, we would not have injuries,” Athletic Training Director Matt Young said.

The American Academy of Pediatrics believes that time off, strength and flexibility can reduce the chance of injury. Pepperdine follows similar beliefs.

Young works with all athletes before, after and during the season to condition and strengthen their muscles in order to prevent injuries beforehand.

Beach Volleyball Coach Nina Matthies said she relies on trainers like Young because they help the team take a preventative approach.They pre-screen an athletes’ whole body the first year to check for weakness.

Her team has been lucky and has not had any serious injuries.

“We have the time do some diligence with research and make sure each kid is taking care of themselves physically,” Matthies said. “By the time January (season) comes we are pretty good to go.”

Men’s Volleyball Coach David Hunt also puts faith in the prevention process.

“I listen to the strength conditioning people and the trainers,” Hunt said. “I emphasize to the guys the importance of those two people.”

Athletics Director Steve Potts works with athletes on injury prevention. One of Pott’s biggest concerns is watching out for concussions. His goal is to make sure all athletes are up-to-date on concussion protocol.

“We’re certainly mindful of concussions these days,” he said. “ We spend a lot of time in concussion education and concussion monitoring.”

Diagram shows the typical injuries Pepperdine athletes face.

The injury

Each sport is more prone to certain injuries. Young said he sees more serious injuries in contact sports.

The most common sport injuries are sprains, strains and knee injuries, according to Medlineplus, the National Institute of Health’s online medical library that provides information on diseases, conditions and wellness issues.

Potts said it usually takes one chronic injury or several damages to become career ending.

“We’ve had student athletes that have had multiple knee injuries and multiple surgeries on their knees,” Potts said. “You just get to a point where you can’t perform anymore.”

Hunt said the most common injuries in men’s volleyball are ankle injuries, dislocated fingers, torn hip and torn rotator cuffs.

Baseball Coach Rick Hirtensteiner said the ones they watch out for the most are elbow and shoulder injuries. The team is dealing with additional injuries as well. First-year player Dane Morrow is suffering with an abdominal injury.

The aftermath

When an athlete is injured, they face more than just the physical effects. Pepperdine coaches and trainers make it a priority to help their injured athletes recover mentally and physically.

Sports Psychologist Cooper Casey, who has a doctorate in counseling psychology, said she approaches severe injuries from a Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder perspective.

“It is a major trauma,” she said. “It is not just a setback or a roadblock. It can be a threat to identity.”

Casey works with athletes daily and said they often use their sport as stress management.

“Not only are they blocked from participation and training, their sport is also their coping skill for everyday ups and downs,” Casey said.

Hirtensteiner said it’s important for teammates to come together and support an injured player. It can be hard for an injured athlete to go to practices and games and not be able to participate.

“We absolutely have them come to practice and we make them do something,” Hirtensteiner said. “While they can’t practice, they can feed a machine or be apart of some drill that they can participate in.”

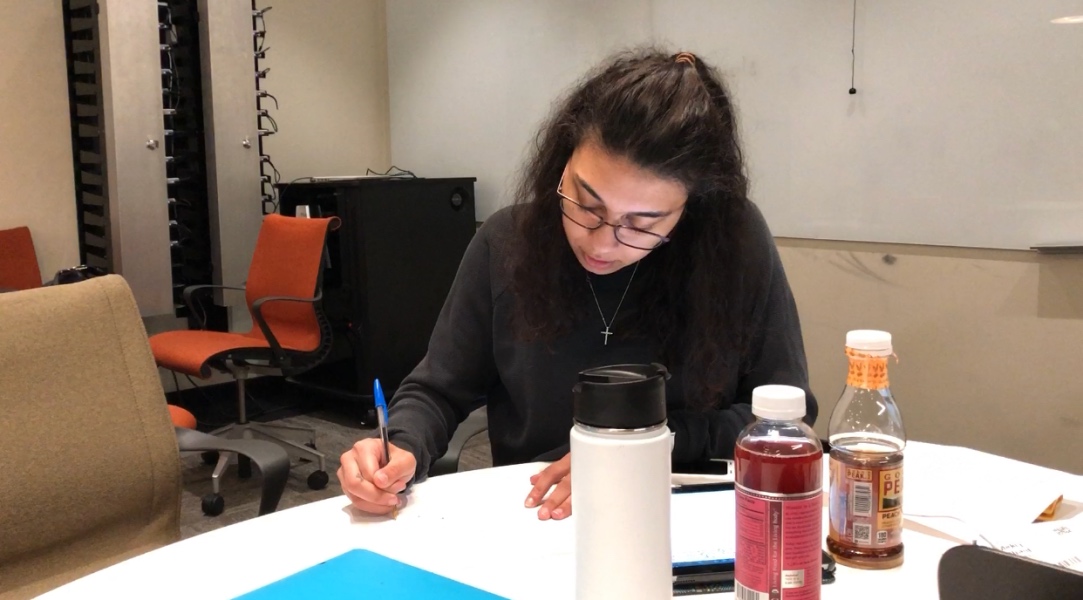

Morrow, who is undeclared, said he still struggles with the emotional impact that comes from being injured and not being about to play. Injured athletes spend most of their time studying the ins and outs of their game.

“You want to be out there playing and getting better, but you can’t,” he said. “Everything you’re doing is mentally practicing.”

Morrow has to be careful with how hard he throws now, because his torn oblique could come back. His teammates who have been through this before have advised him not to rush it, take it easy and let him know that he has time before the season starts in the spring.

“The athletic trainers are really good about making sure we come back slow and easy,” Morrow said.

For his recovery, he does ultrasound therapy, stem therapy and oblique stretching.

After spending a full year recovering reconstructive knee surgery to repair his meniscus tear, Cole said he looks back at that experience as a miserable time.

“Your life is flipped upside down,” he said.

Apart from the mental recovery, the physical part was just as challenging. Cole said it affected every part of his life.

“It was so tender for so long that when I moved in my sleep I would wake up,” he said. “For five months I barely slept.”

Caroline Archer, a track athlete and first-year undeclared major, suffered from an inflamed tendon in her foot. The gradual injury occurred at the beginning of the 2017 track season. Her trainers benched her.

“I had to stop running completely for a month,” she said. “It was pretty disappointing because I wanted to prove that I had a reason to be on the team.”

Potts said athletes face rehabilitation and sometimes surgery, along with working through the emotional baggage of not getting to play the sports they love.

“There’s the emotional challenge of just how hard they’ve worked to prepare for the season,” he said. “Now that’s all gone.”

He said athletes will always wonder is they will be able to come back stronger or as good as they were prior to the injury.

Cole is dealing with the same thoughts as he begins playing volleyball again. He said he cannot jump as high anymore, but is training to get back to where he was. He felt joy when he was able to be back in the game.

“I almost cried,” he said. “I am not much of a crier but I was pretty close.”

Pepperdine’s role

Pepperdine works with their athletes to try and make the recovery process a little easier for them.

Potts said when an athlete is hurt, they never consider taking away their scholarship. They do their best to work with the athlete so that they can get to a point of competing again. In the rare case that an injury would be career ending, their scholarship would not be affected.

Hunt said they look out for their athletes and want the best for them.

“The standard is a little bit higher here,” he said. “I think that’s a good thing.”

Pepperdine athletes also have the advantage of having skilled trainers and doctors to provide the best services. Dr. Gary Green is Pepperdine’s physician and has been with the school for 20 years.

“Dr. Green is the medical director for Major League Baseball,” Potts said. “He is certainly qualified to deal with our student athletes.”

Pepperdine’s campus is not an easy place to get around when injured. Potts said the Department of Public Safety works with injured athletes to help them get to their classes.

There is still work that can be done to make it easier. Cole complained that DPS could not arrive quickly enough for him to make it to class on time. He suggests that Pepperdine should add more elevators and work with the professors so everyone is on the same page.

“There are 57 steps from the bottom of Lovernick to the top of the floor,” he said. “I still remember it.”

Meghan Payton completed the reporting for this story under the supervision of Dr. Christina Littlefield and Dr. Theresa de los Santos in Jour 241 in fall 2017. Dr. Littlefield supervised the writing of the web story.