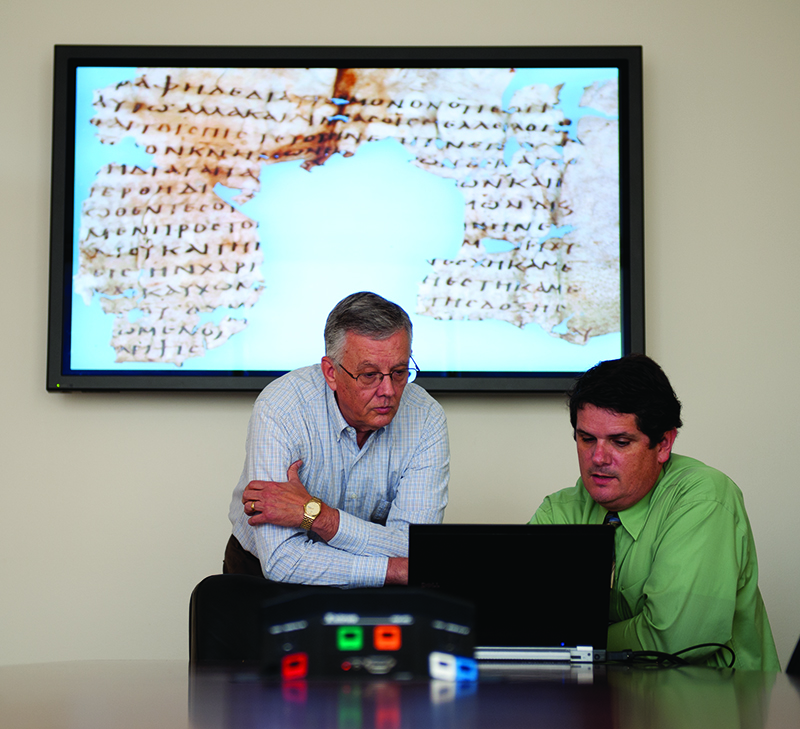

Pepperdine’s religion professors walk a tightrope when instructing students in Religion 101, 102 and 301.

With approximately 78 percent of undergraduates adhering to Christian denominations, many people in Pepperdine’s mandatory religious GEs said they feel like they are relearning information they grew up learning in church. For the 22 percent that aren’t Christian or only nominally so, Religion 101 and 102, which cover the Old and New Testaments, may be the first time they’ve studied the Bible.

“Religion GE classes present a number of challenges, the first of which is that most students resent having to take them and don’t see them as having any utilitarian purpose,” said Ira Jolivet, a religion professor teaching the Rel 102 and 301 GEs. “Also, my classes are usually comprised of Atheist, Agnostic, Buddhist, Muslim, Jewish, as well as Evangelical Protestant and Catholic-Christian students.”

Religion professors must be members of the Churches of Christ, Pepperdine’s own Christian heritage. Professors strive to teach religious material without coming off as proselytizing, said Timothy Willis, chair of the Religion Division and an Old Testament professor.

“We hold up as paramount two of the affirmations attached to Pepperdine’s mission,” Willis said. “‘That truth, having nothing to fear from investigation, should be pursued relentlessly in every discipline.’ And ‘That spiritual commitment, tolerating no excuse for mediocrity, demands the highest standards of academic excellence.’”

Religion professors think about this challenge in two ways: as members of one denomination speaking to members of other denominations, and as followers of one religion speaking to those who are not followers of that religion, Willis said.

This means that the goal is not the same as the goal at church, to bring people to salvation, Willis said. The academy might be a stepping-stone on the road to the goal of a church, but not necessarily so.

“If you talk about religion as something simply to be examined, then you leave out the personal commitment and allegiance that is so important to believers,” Willis said. “It seems like you are not fully honoring the religion. So the university has to walk a fine line between activities that expect full ‘buy in,’ and those that require only a consideration of facts and possibilities.”

Hence, religious students can feel disappointed by talk about religion in an academic environment, Willis said.

A fall 2013 survey of 50 participants found roughly 80 percent of students believe professors walk the tightrope well and do not push religious beliefs on students when teaching Rel 101, 102 or 301.

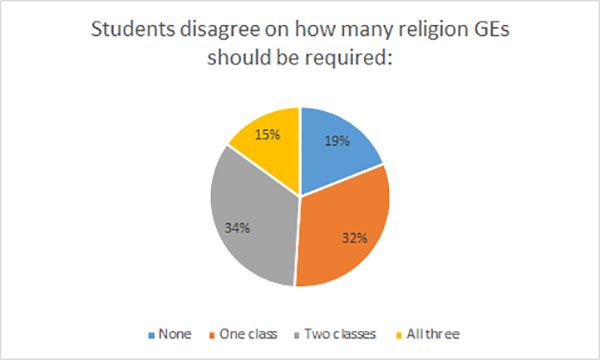

The survey also showed that most students would keep at least one religion GE. Only 19 percent said they would get rid of the requirement altogether, 32 percent said one class would be sufficient, 34 percent said two and 15 percent said three. Frustrations, however, abounded for both religious and non-religious students.

“As someone who has read the entire Bible, and has learned extensively about bibliology, theories of authorship, translations, and historical authenticity, and was always taught both sides of the issue and allowed to choose for myself, Rel 101 disgusted me,” said junior Jessie Ruzich, a Christian who leads a club convocation and Bible study.

“I was incredibly frustrated that my Christian university couldn’t start with the presupposition that the Bible is the inerrant word of God,” Ruzich continued. “The textbook was written from the perspective that Israel was just another ancient, cultic, theocratic society. There was no acknowledgement that any of it was true.”

Pepperdine’s tradition supports the Bible’s inspiration by God, but not its infallibility, professors said.

Ruzich said she desires a class where professors preach the Gospel. But Willis said that “is not the educational mindset that we find to be appropriate in a liberal arts setting such as Pepperdine’s.”

Although the religion GEs may not be ideal for those with religious backgrounds, the fall 2013 survey showed that 62 percent of Christian students believe their religious background aids them in the classes.

The poll also showed that 65 percent of students with no religious background felt hindered in the religion GEs.

“As someone with a limited knowledge of biblical history prior to freshman year, I appreciated that the curriculum covered in Rel 101, 102, and 301 was taught from an academic perspective,” junior Steven Lesky, a Christian, said. “Faith is open to interpretation for each individual person, and if the courses were taught from a spiritual perspective they would inherently contain subjective biases.”

Professor Ronald Cox, who teaches Rel 102 and Rel 301, agreed.

“The academic approach to teaching scriptures is helpful,” Cox said. “It ideally gives everyone a seat at the table to discuss the New Testament; though students may not share my faith or agree with my convictions regarding it, we all usually agree about the methods we are using, usually the same that you find in history, social sciences, art history and other classes.”

Many non-Christian students said they do not like the required religion GEs.

“Religion classes should only be required for religion majors, and otherwise should be offered as electives,” Michael Sweat, a junior and an atheist, said.

He said the classes made him feel like people were forcing their views upon him.

Junior Lauren Mock, a Roman Catholic, said she found Rel 101 and Rel 102 to be “heavy on the biblical context” and “too intense.”

Despite many non-Christian students disliking religion requirements, professors and Christian students said the religion GEs come with the Pepperdine experience, and should be expected and accepted. Yet, professors must deal with those in disagreement.

“(Students) don’t have to be religious if they come here,” said Gary Selby, professor of communication and director of Pepperdine University’s Center for Faith and Learning. “In fact, I would argue that they will be treated with a unique level of care and hospitality … But obviously, they need to be aware of Pepperdine’s ethos before they come.”

The religious diversity is why religion professors are often more careful not to come off as preaching than professors in other disciplines, Selby said.

“Of course, we want faith to be part of the conversation,” Selby said. “But we are always mindful that not every student who walks through our door shares that faith.”

Cox said he works from three main convictions.

“First, that students have freely chosen to come to Pepperdine, a Christian school, so teaching on the seminal documents of Christianity should not be a surprise to them, whatever their religious commitment,” Cox said. “Second, ‘hospitality’ is fundamental to Christianity … to create a hospitable atmosphere in the classroom where all are welcome and all can participate. Third … teaching Rel 102 is the highest honor I have at Pepperdine … to share a set of writings that I treasure with students and to hopefully inspire them to see for themselves how beautiful and meaningful those books are and how relevant they are today.”

Professors said they have wrestled with how much to share and when.

“I struggled with sharing my personal faith in class for a few years before I came to the conclusion that I owe it to my students to be honest with them,” Jolivet said. “I don’t mind telling them my story if and when I feel it is appropriate to do so without being ‘preachy’ about it or by supposing that any of them will follow the same path that I did.”

Religion professors said they bring their Christianity to the table in class in different ways.

“I fail as a follower of Christ if I don’t embody his message in my life and words,” Cox said. “But that does not mean I use my Rel 102 class to convert people. The class is about becoming aware of and investigating the New Testament. The lectures I provide … are not designed to tell students what to think, but to model for them how to think about Scripture, giving them tools to take Scripture seriously … and to appreciate what it means for themselves.”

Ultimately, Cox and other professors said their desire is to show students the love of Christ.

Teaching people from many faith backgrounds is a “wonderful opportunity,” Rel 301 Professor Dyron Daughrity said.

“I pray in class at times,” Daughrity said. “I also try to show Christian compassion and concern for my students; faith is a part of the human condition.”

The primary challenge is getting students with no religious experience in their background or those who have chosen not to accept the claims of Christianity to see the relevance of religion, Willis said.

“We try to show them how religion affects the ways we view ourselves as human beings, the ways we interact with one another, and how those views have shaped the past and present,” Willis said.

In the survey, 68 percent of students said religion GEs have not affected their faith or lack thereof.

Low motivation or apathy prevents non-religious or non-Christian students from learning to appreciate aspects of religions different than their own, Religion Professor Danny Matthews said. He views his Rel 101 class as “a chance to bear witness to the students about the religious significance of the Old Testament and the meaning for faith today.”

Some schools feel coercive in the way they approach faith and learning, while some Christian schools assume or even require that everyone subscribe to the faith to which the school is connected, Selby said. Pepperdine occupies a unique position on the landscape of higher education.

“Pepperdine is attempting to be in the middle — to be true to its Christian mission, that of nurturing Christian spiritual formation as well as intellectual and social formation, while also being welcoming of people who represent a broad range of beliefs,” Selby said.

Some students said they do see the relevance.

“While I still don’t connect well with the gushing #soblessed side of Pepperdine, I have been beyond challenged, refreshed, amazed and enriched by it,” Ruzich said. “It’s the best thing that has ever happened to me.”

Lauren Kerns completed this story in Dr. Christina Littlefield’s fall 2013 Jour 241 class.