The goal of every single collegiate athletic program is simple — to win a national championship.

But the universities competing for those titles couldn’t have a great team — or even a team at all — without recruiting, the process of identifying the high school athletes that college coaches want in their programs, and convincing those athletes to choose their particular school.

Even at a mid-major school like Pepperdine University, recruiting is a non-stop national, and sometimes international, search for talent with the future success of the program hanging in the balance.

“Finishing second in recruiting doesn’t help you at all,” Pepperdine Athletic Director Steve Potts said. “We have to finish first as often as we can.”

While Pepperdine players, coaches and administrators alike describe recruiting as cutthroat and pressure-packed, the process also allows players to build meaningful relationships with coaches and teammates, grow both in and outside their sport, and fulfill their dreams of becoming Division I student-athletes.

Ahead of the curve

To identify the best student-athletes, coaches cast a wide net.

For his women’s volleyball program, Head Coach Scott Wong scouts “thousands upon thousands of kids” per year, with the end goal of getting three or four to commit.

But when just under 8 million kids play high school sports nationwide, according to a National Federation of High School Associations figure, how do you find the right ones for a certain program? Coaches agree: it’s all about who you know.

“In this game, you can’t be everywhere,” Delisha Milton-Jones, women’s basketball head coach, said. “So you need connections. You need to have people that you trust that understand what you’re looking for.”

For some sports, such as soccer and volleyball, coaches look to younger players to get a head start, often recruiting seventh and eighth graders.

Despite it being an industry standard, Women’s Soccer Coach Tim Ward called recruiting middle schoolers “not smart.”

“You’re gambling a lot,” Ward said. “We don’t need great 15 and 16-year-olds. We need great 19, 20 and 21-year-olds.”

Katy Byrne, a senior sport administration major and soccer player, agreed, even though she was recruited in middle school.

“It’s weird, just because you’re so young that you don’t know what you want in a college yet,” Byrne said. “It would just shock me how the college coaches would make such big offers to players at such a young age when you have no idea how they’re going to develop.”

But in other sports, that’s part of the secret. While coaches can potentially gain an advantage by being the first to make an offer to a particular recruit, nothing binds the school’s offer until the recruit has locked themselves in by signing it.

Colbey Ross, a sophomore sport administration major and basketball player, thought he had four Division I offers after his sophomore year of high school but after his junior year, they had all been rescinded.

“Once you get offers, then you get confidence when you’re playing, things start to come easy,” Ross said. “But once you get late in your junior or senior year and you don’t have those offers, it’s crunch time. It’s like … I gotta prove myself and do whatever it takes to get people’s attention.”

The mental game

Yasmine Robinson-Bacote, a senior liberal arts major and basketball player who was recently named the West Coast Conference Player of the Year, thought the pressure to perform for recruiters had a psychological impact.

“It’s a very cutthroat business,” Robinson-Bacote said. “You’re only as good as your last game. So that’s a lot of pressure on you. Every game feels like a championship game.”

On the other hand, Reese Alexiades, a redshirt sophomore media production major and baseball player, didn’t mind the eyes on him.

“If you know someone’s watching you, then everything’s locked in,” Alexiades said. “You kind of just need to play and do what you need to do. Honestly, for me, I feel like I do better.”

Still, Alexiades acknowledged the difficulty of getting a big break.

“You have to get lucky to get your name out there and get recruited, because there’s so many players and so little opportunities for coaches to see you,” Alexiades said. “And they could see you and you could strike out three times, and they’d just say ‘See ya.’ You could be a great player and they won’t know it.”

Sales pitches go both ways

Given how hard it can be to stand out in the crowd, many recruits take matters into their own hands.

Ward estimates his program staff receives 3,000 emails a year from recruits trying to pitch themselves. Wong estimates his program gets 100 per day, and that “maybe one” of those kids could conceivably play at Pepperdine’s level.

Those long odds don’t stop many from trying to get noticed, however.

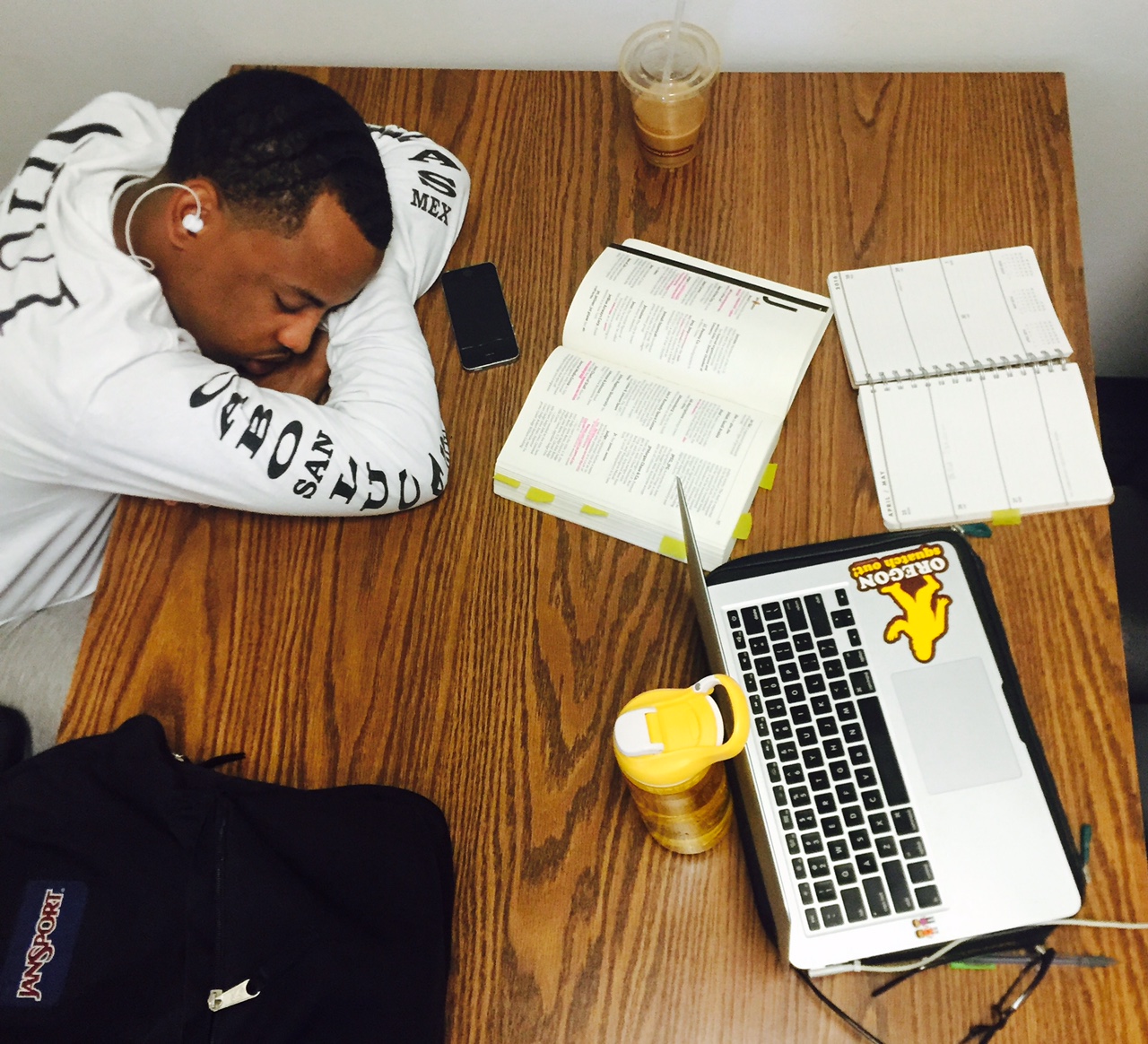

Darnell Dunn, a senior intercultural communication major and basketball player, was left without basketball options after a year at a Division II college. Dunn said he sent emails to over 30 colleges introducing himself along with his GPA and high school statistics but that only a few responded.

Although he thought about going to a school where he would “just be a regular student and get my degree,” Dunn’s reasoning for reaching out to those schools was simple.

“I wanted to keep playing,” Dunn said. “And I believed in myself.”

Dunn was able to land at Miami-Dade Junior College and transferred to Pepperdine after a successful season there.

Following the rules

Recruiting is a heavily regulated activity. The NCAA Manual chapter on recruiting alone is 65 pages of rules.

But since the stakes for recruiting are high, with championships and sometimes jobs on the line, rules are bent or broken frequently.

While the Washington Post has covered big-time scandals like the one involving the Ole Miss football program and CBS Sports outlined the current college basketball corruption investigation involving the FBI, the reality is that smaller violations with much smaller consequences are a regular occurence.

“A sign of a healthy compliance office is a healthy number of violations,” Amanda Kurtz, Pepperdine associate athletic director for Compliance, said. “When you have a manual that thick, and there are some pretty nitpicky rules, you cannot be perfect all the time.”

The vast majority of violations are Level III, which have direct and minor consequences. For example, if a coach contacts a recruit outside a permitted period, then they would be unable to speak with that recruit for a determined amount of time, NCAA Faculty Representative Don Shores said.

When a program commits serious Level I violations, more drastic actions are taken, such as vacating wins, postseason bans or scholarship reductions.

In 2012, Pepperdine self-reported Level I violations that involved giving illegal academic scholarships to athletes on top of the allowed athletic aid. The NCAA Committee on Infractions ruled that Pepperdine failed to monitor its athletics program properly and enforced a scholarship reduction across five sports, vacated wins for three sports, and placed the entire athletics department on a three-year probationary period.

The reason this was even possible as a violation is that not every student-athlete is on a full scholarship. While that is the case for major sports like football and basketball, the majority of college sports are called “equivalency sports,” which means they have a limited number of scholarships that can be chopped up in any way and distributed.

Soccer has the equivalent of 14 scholarships for 26 to 28 players. Baseball has 11 scholarships to spread around 35 roster spots.

So for coaches of these sports, the added recruiting wrinkle is determining how much of a scholarship a certain player is worth. Schools with a higher tuition rate, like Pepperdine, could potentially be at a disadvantage if families are needing to pick up most of the tab.

Sealing the deal

Wong said that “the core of recruiting is relationships.”

Building a relationship is a vital part of the recruiting process. Programs want to feel like a family, both inside and outside the sport.

This is particularly true with Pepperdine, as a smaller and community-oriented school.

“Relationship means everything to us,” Milton-Jones said. “If we’re not able to talk to them as much as we would like to, then that hurts us. Alabama or USC could come in late in the recruiting process with all the amenities, and glitz and glamour, and just swoop in and take a kid.”

A poll of 40 Pepperdine student-athletes shows that, for the most part, college coaches were in frequent contact with them as high schoolers.

“It’s almost like speed dating,” Robinson-Bacote said. “I know that sounds weird, but it’s like … these random people are calling your phone, and you have ‘x’ amount of time to get to know them, as well as to decide if there’s a ‘second date,’ or a second phone call. I would say it’s the most intense speed dating a person could ever experience.”

At the end of the day, the recruit will choose what’s best for them based on what’s important to them, and Ward said that’s the way it should be.

“We don’t want a recruit of ours to settle for us,” Ward said. “If you’re excited by a facility they have that we don’t, maybe you should go there. But what I can promise you here is you’re going to be loved, you’re going to be respected, and we’re going to help you grow.

“So it’s funny, it’s almost the counter-recruit,” Ward continued, “but I say when the dust settles, if you’re in love with Pepperdine, the reason we invited you on this campus is because we think you can be exceptional here but we don’t want you here unless you’re in love with us.”

Recruiting doesn’t end after freshman year

Since the player/coach relationship is often a huge factor in commitments, entire rosters can be upended when there is a coaching change.

When Pepperdine fired former Men’s Basketball Coach Marty Wilson at the end of the 2017-2018 season and hired Lorenzo Romar, the players braced for a shakeup.

“It definitely scared us all a bit,” Dunn said. “The guys that brought you here are no longer here, so you expect the new staff to come in and want their own people.”

Ross took the news hard.

“I was bawling,” Ross said. “(Wilson) was my guy. He trusted me.”

Ross’s bond with Wilson, the coach who recruited him, was so strong that he initially wanted to transfer to whatever school Wilson ended up at.

Multiple talks with Romar eventually convinced Ross to stay but it was a gradual process.

“I’m thinking, I want to stay,” Ross said, “But … not to say I can’t trust you but I haven’t built the relationship yet.”

Although four players from the 2017-2018 team did transfer, Ross remained at Pepperdine, and set school single-season records for assists and made free throws during the 2018-2019 season, in addition to being named to the all-conference team.

Ross now considers Romar “definitely one of the best coaches I’ve ever had.”

“I think Lorenzo is the best recruiter in the country,” Potts said.

Romar did not have time to be interviewed for this story.

Ross’ experience proves that the skill and need for recruiting never stops, even when the athlete is committed and on campus.

“You have to make sure your student-athletes that you’ve worked so hard to get here have the kind of experience that makes them want to stay here,” Potts said.

Why Pepperdine?

The poll found academics and the coaching staff were the two primary factors for why student-athletes choose Pepperdine.

“To get the Pepperdine education is a big deal,” Dunn said. “Hands down, compared to the other schools I had, it’s just something I couldn’t pass up.”

Coaches and players agreed that Pepperdine is a special place.

“At Pepperdine, the fiber of this university and the way the athletic department is structured is incredibly unique,” Adam Schaechterle, men’s tennis head coach, said. “We don’t shy away from the fact that Pepperdine is different, we celebrate and sell that.”

No days off

The most underrated aspect of recruiting is how much of a sheer “grind” it is.

Wong split the weekend before he was interviewed between Las Vegas and Kansas City for two separate tournaments, pulling 13-hour days in a convention center that held 120 volleyball courts.

Milton-Jones visits and watches recruits play in games while on road trips during the season for her team.

When Schaechterle became the tennis coach in May 2018, he visited six European countries for recruiting within his first month on the job.

“People that don’t fully get what we do say ‘Hey, you’re just in-season for the fall,’” Wong said. “‘What do you do the rest of the year? It must be a great job just hanging out in Malibu.’… They don’t get it. Recruiting is non-stop. If a recruit needs to call at 10 p.m., I need to be able to take a call at 10 p.m.”

All the long hours and long days come with the goal of seeing and connecting with as many people as possible, in the hopes that the perfect few will lead the program to success several years down the line.

“Every coach we have has to put that kind of effort into recruiting,” Potts said. “If we don’t, then we’re not going to get better.”

Paxton Ritchey completed the reporting for this story under the supervision of Dr. Christina Littlefield and Dr. Theresa de los Santos in Jour 241 in Spring 2019. Dr. Littlefield supervised the web story. Dr. de los Santos supervised the video package.