Every night Alejandro gets to work at 11 p.m. and prepares himself for the long night ahead. While everything else in Los Angeles is beginning to close, the Los Angeles Wholesale Produce Market is preparing to open.

Alejandro, who refused to give his last name for privacy reasons, chats with the vendors around him and checks his phone for customer requests and product reviews while he waits for his produce shipments to come in. By midnight, the trucks are finally starting to arrive. The market is buzzing with semi-trucks moving in and out, loaded with flats of tomatoes, avocados and strawberries. While others around the city are catching up on their sleep, a crew pushing dollies and driving pallet movers unload the produce and begin to stack the flats in front of the stands.

Alejandro has been selling produce at the Los Angeles Wholesale Produce Market for 34 years. His produce comes from Mexico and Arizona as well as California’s Coachella Valley.

For less than $20, you can purchase nearly 15 pounds of avocados — about $1.30 per pound. About $13 will buy you 10 pounds of strawberries.

The Los Angeles Wholesale Produce Market has provided local restaurants with fresh produce at the lowest possible cost since 1984. While these low prices benefit the restaurant owners, at what price does it come to those who supply the produce?

Interviews with nonprofit advocates and other experts suggest it is a hefty one, as low produce prices are often the result of unfair wages and work conditions on the backs of immigrants.

“They are treated like disposable goods,” said Jorge Cabrera, the coordinator for the Southern California Council for Occupational Safety and Health. “When they get injured they get deported.”

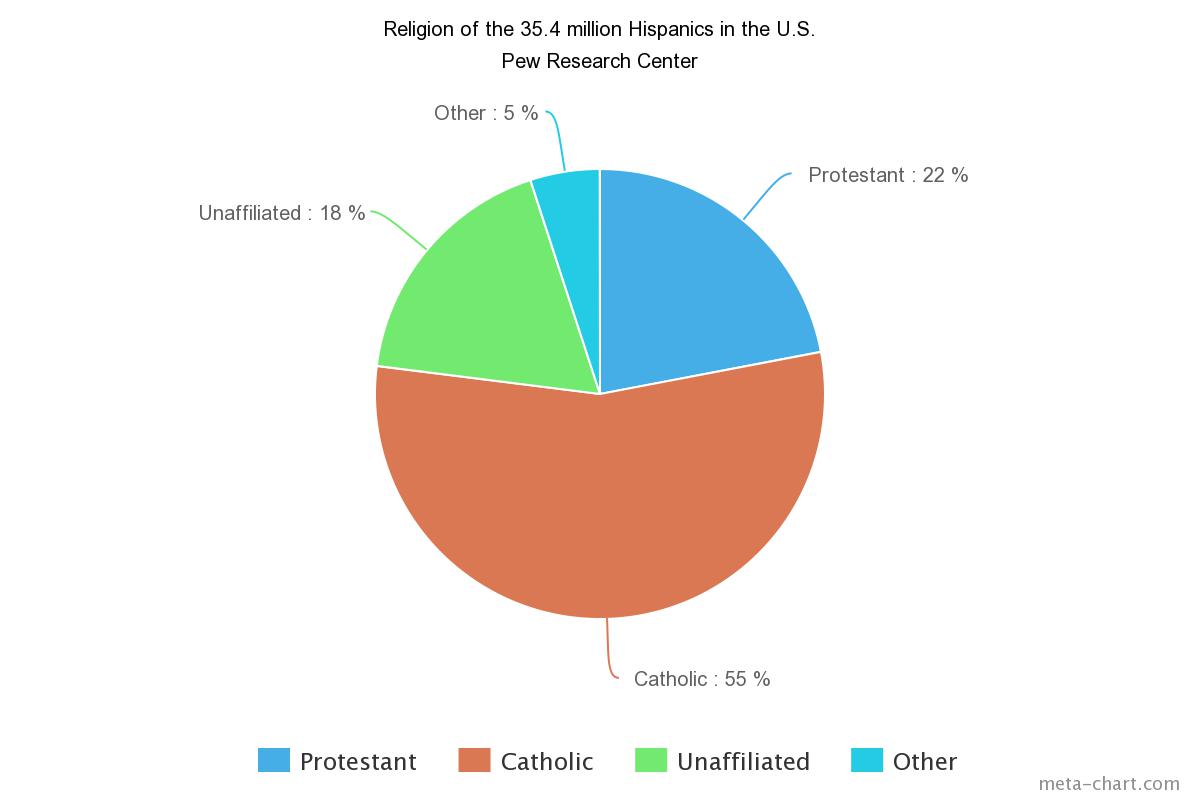

According to a 2012 study by the Pew Research Center, 26 percent of farmworkers are undocumented with California having the second highest amount of undocumented laborers at 9.4 percent. This same study also found that the average household income for undocumented workers was $36,000. Other studies have put the percentage of undocumented workers far higher and their salaries far lower — indicating how hard it is to calculate a population in the shadows.

Foreign-born workers are more likely than native-born workers to work in low-skilled, low-education jobs. 2010 U.S. Census data shows that 25.1 percent of immigrants work in service, 13 percent in construction and 15.5 percent in the production/transportation industry. These are the industries in which immigrants most commonly get mistreated, interviews with Cabrera and other experts suggest.

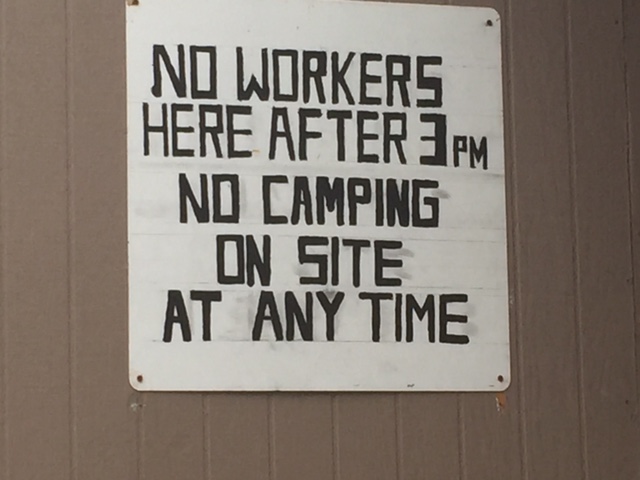

Federal law has tried to help ensure employers meet safety standards and work conditions. Congress passed the the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act in 1983. It calls on farm owners to take responsibility for worker safety. The act protects temporary workers that work through farm labor contractors. According to the Farmworker Justice Organization, before Congress established the act, some growers classified farmworkers as “independent contractors” instead of “employees” to avoid taking responsibility for them.

The wages and working conditions for most workers who produce the nation’s fruits and vegetables are still inadequate, according to a 2014 report from the Farmworker Justice Organization. The report indicates many farmworkers continue to experience wage theft, dangerous housing and transportation, and other illegal employment practices as a result of employers maneuvering through the system.

The report claims that many growers still escape responsibility under employment and immigration laws by claiming that their farmworkers are employed solely by outside contractors.

Some 70 percent of farmworkers are immigrants, according to the Farmworker Justice Organization. Their status means they are hesitant to speak up when they aren’t being paid properly, are suffering on the job or get injured, interviews with experts suggest.

In a 2002-2004 National Agricultural Workers Survey, surveyors asked farmworkers about injuries they had within the last year while working on a U.S. farm or traveling to or from a U.S. farm.

The most common types of injuries reported were muscle injuries, categorized as a sprain, strain, torn ligament, or traumatic rupture (39 percent). Next were cuts or lacerations (24 percent), and finally broken bones or fractures (13 percent). These injuries impacted the ability of immigrants to work and required first aid or other medical treatment.

Roberta “Bobbi” Ryder, the president and CEO of the National Center for Farmworker Health, wrote in an email that most immigrants that come to the U.S. arrive healthy.

“The males who come to United States to work in agriculture are very healthy and ready to work,” Ryder wrote. “Backbreaking labor and use of ladders and knives and exposure to the elements and sometimes rodents all create a less than ideal living arrangement.”

In addition to injuries, undocumented immigrants may also have higher health needs than documented immigrants. Undocumented female immigrants face back pain, vision problems, dental problems, flu/cold and allergies at higher rates than documented female immigrants, according to a 2005 study done by Dr. Khiya Marshall, who specializes in social and behavioral sciences and community health at the University of North Texas. The only category of health in which documented immigrants scored higher was high blood pressure.

Low income, substandard housing, inadequate or unsanitary living facilities, limited formal education, ethnic segregation and discrimination, poor nutrition and stress all contribute to health concerns, according to a study by Patrick Rivers, a professor of health care management at the University of North Texas, and Fausto Patino, who holds a doctorate in economics from the University of Minnesota.

Nonprofit organizations are often the only means of relief for undocumented workers hurt on the job, as they don’t often have access to worker’s compensation rights. For the many undocumented workers who have no access to health insurance, nonprofit clinics or emergency rooms are their only option as well, where quality and cost of care range widely.

The Southern California Council for Occupational Safety and Health and the CARWASH Campaign are two such organizations that help.

The CARWASH campaign works to provide immigrants with healthy work conditions and fair wages by organizing immigrants in the carwash industry. In doing so they provide safer, humane and quality working conditions for carwash workers.

SoCalCOSH is the Southern California division of the National Council for Occupational Safety and Health. COSH organizations around the U.S. are committed to promoting worker health and safety through training, education and advocacy.

“Undocumented immigrants experience many different (problems) in their respective industries,” said Flor Rodriguez, the community organizer/worker and center coordinator at the CARWASH Campaign in Los Angeles. “Some aren’t able to get water during break, are exposed to chemicals and don’t receive work breaks.”

The chemicals that car wash employees are exposed to include detergents and cleaners but also substances such as hydroflouric acid, which can lead to burns, calcium break down in bones and cardiac arrest. Even inhaling hydrofluoric acid vapors allows the chemical to be absorbed into the bloodstream where it starts to break down calcium found in bones. This break down in calcium not only weakens bones but can eventually lead to cardiac arrest, according to a 2011 article entitled “Teaching Chemical Safety” from carwash.com by Debra Gorgos.

According to the article, ammonium bifluoruide is another dangerous chemical that can be used as a finish for cars in the carwash industry. According to Hill Brothers Chemical, an industrial chemical supplier, ammonium bifluoride can cause irritation to the skin and eyes. Prolonged exposure to the chemical can cause nausea, vomiting and fluoride poisoning, which can eventually lead to death. Fluorosis, which can also result from repeated high exposure to the chemical, causes the teeth and bone to break down, which can lead to pain and disability.

When handling both chemicals, the article recommends that gloves, aprons and goggles are used, but Rodriguez and Cabrera believe far too many carwash employees are denied these safety measures.

“Most of their eyes look as if they’ve been drinking all day,” Rodriguez said. “They’re really red from the chemicals, the sun, the dirt. They don’t have access to gloves or safety training.” In the farming industry, workers are at high risk for pesticide exposure. Field workers must be trained on pesticide use, according to the Worker Protection Standard. But pesticide exposure causes farmworkers to suffer more chemical-related injuries and illnesses than any other workforce in the nation, according to the Farmworker Justice organization. Another pesticide danger for farmworkers is the limited amount of information they receive about the pesticides they are exposed to, according to the National Center for Farmworker Health (NCFH). Often times they aren’t told which pesticides are being used and farmworkers have limited control over the amount of pesticides used. The center did a study of 300 North Carolina farms, where researchers found 75 percent of workers had access to water but only 44.3 percent were given soap to prevent pesticide absorption. In the same study, 34.8 percent of workers reported being given pesticide safety instructions by a supervisor and 14.8 percent of workers were provided with pesticide safety equipment. Farmworkers suffer serious short and long-term health risks from pesticide exposure. Short-term effects include stinging eyes, rashes, blisters, blindness, nausea, dizziness, headaches, coma and even death. Long-term effects include infertility, birth defects, endocrine disruption, neurological disorders and cancer. Workers often mistake these symptoms for the flu, according to the NCFH. As a result they don’t seek the care they need.

Many of these immigrants are so used to these conditions, that they don’t even identify dangerous work conditions as problems, Cabrera and Rodriguez said.

“I knew a worker that had a chronic cough all the time as a result of working from the factory,” Rodriguez said. “When he finally addressed the problem to his employer he was told his work wasn’t needed anymore.”

Many carwash workers take on second jobs within the restaurant industry where they are commonly mistreated, Rodriguez said.

“(When working at restaurants) they aren’t given lunch breaks and overtime isn’t being given,” she said. “They receive no health/safety training.”

Rodriguez and Cabrera said these poor working conditions are standard for undocumented immigrants within the service industry.

“People think that cheap workers don’t matter and that no one will advocate for them,” Cabrera said.

Low wages also make it difficult to better their lives.

“The lack of proper compensation leads to poverty because the cycle can’t be broken,” Cabrera said.

Mental problems also have a negative effect on the family.

“(Farmworkers) slip into some of the worst habits that we have taught them as a society which includes drug use and abuse,” Ryder said. “Loneliness for family members left behind also causes great distress, and while more psychological in nature can create very real medical issues.”

Poverty creates stress, Rodriquez said.

“Stress stems from not having enough to eat and the lack of sleep affects their ability to work,” Rodriguez said.

The victims of these labor conditions aren’t restricted to a certain country. Immigrants from all over the world are taken advantage of because of their ‘undocumented’ status, experts said.

“They are more diverse than people think,” Cabrera said.

Immigrants and their need for healthcare

Undocumented farmworkers and other immigrants rarely have access to health care insurance or the money to pay for regular health care needs. The most-utilized services/diagnosis by migrant health centers are oral exams, diabetes and health supervision for infants or children, according to a 2011 study of 903,933 farmworkers done by the U.S. Department of Health and Resources Services and Administration.

Most undocumented workers are excluded from the provisions of the Affordable Care Act. Some believe that since undocumented persons don’t pay taxes they should be excluded from taxpayer-subsidized health care.

However, according to tax specialist Mark Jason, many pay taxes with false security numbers. Only the cash economy workers do not. He’s trying to better capture that tax base to provide services for immigrants and bring them out of the shadows.

Local clinics are often the frontlines for access to health care, but the available care ranges widely. In a study of 212 clinics throughout California, the writers found 26 percent of clinics provided care primarily for women. Of a random sample of 42 clinics that were called, all said their clinic received more women than men as patients.

Only 18 percent of clinics provided free healthcare to their clients, with the majority of clinics, 68 percent, providing healthcare on a sliding-scale system. The sliding-scale system allows patients to pay for medical care based on their annual income. In order to qualify for this system, one must provide their three most recent paychecks or pay stubs. For many undocumented workers who are paid in cash, this makes qualifying for the sliding-scale system nearly impossible.

“St. John’s (hospital) will work with us,” Cabrera said of the carwash employees. “If we get an employer to sign a letter saying ‘I get paid this much’ then they can pay based on the sliding scale.”

Visiting a clinic is often as much of a burden as the cost. More than 64 percent of clinics were only open on weekdays, which would mean that visiting a clinic would mean missing a day of pay. For carwash employees, who are only allowed three sick days a year with proof of a doctor’s note, going to a clinic is unrealistic.

Clinics also have limited service. Of the 42 clinics called, none were unable to provide medical testing such as X-rays or blood work in house and had to refer clients to other testing facilities. While clinics are able to provide health checkups and care for those with mild illnesses, injuries are usually treated at the emergency room. When asked where patients should go if they didn’t have health insurance and needed immediate care, every clinic called said to go to the emergency room.

Poor access to health care is magnified by physically difficult jobs. Manual labor occupations such as agriculture, construction and housework put laborers at a much higher risk for physical injury than a white-collar job.

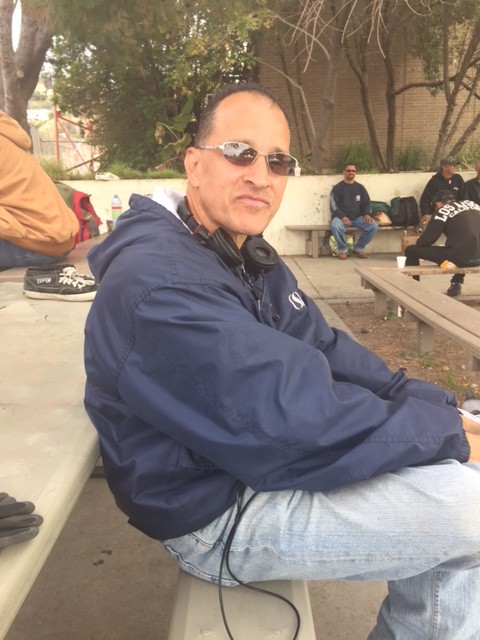

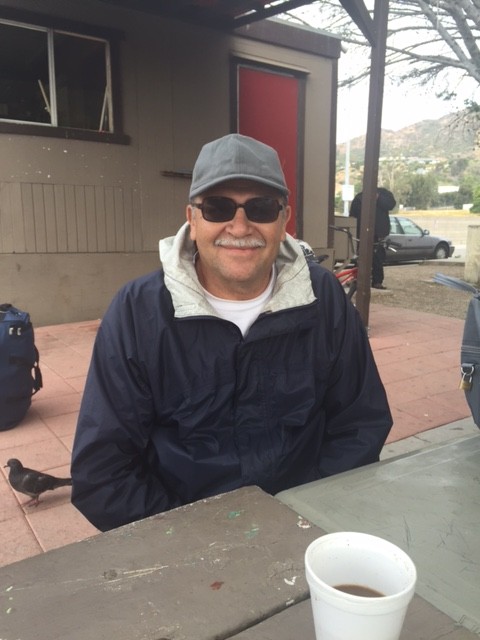

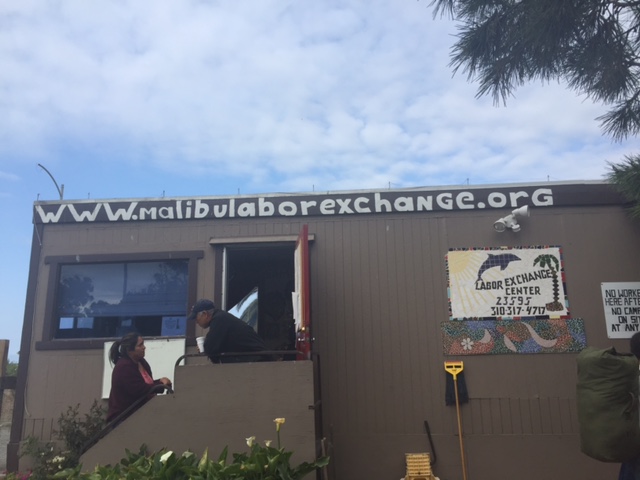

“I typically do all outside work and paint,” said Pedro, an undocumented immigrant who would only give his first name. “I do construction and gardening.”

Thankfully for Pedro, he had never been hurt.

“I’ve been coming here (Malibu Labor Exchange) four years and I’ve never been hurt,” Pedro said. “But if I did, I’d go to the hospital.”

|

|

|

Victor, who has recently started looking for work at the Malibu Labor Exchange, was born in Chihuahua, Mexico and came to the United States in 1992 at the age of 17 to find work.

‘“I did plumbing at first and then dyecasting,” Victor, who declined to give his last name, said. “Now I do painting and work as a handyman.”

Immediately before he became a handyman, Victor worked molding aluminum for seven years.

“It (the work) was very dangerous because it’s really hot,” Victor said. “Hot metal would hit my hand and arm and burn them.”

Victor rolled up his sleeve to show where the molten metal had hit him, some spots were up past the elbow.

While workplace injuries put many undocumented workers at risk, there are other health concerns that immigrants face that are less noticeable and much more deadly, health concerns that Victor knows all too well.

“Every three months I go to the doctor because I’m diabetic,” Victor said, patting his backpack which held several insulin shots.

The clinic that Victor attends is only 30 minutes away by bus and he is able to see the same doctor every time. Victor is thankful to have health insurance which means that he doesn’t pay for his trips to the doctor or for the life-saving insulin.

According to a 2012 study by the University of California, Los Angeles Center for Health and Policy Research, 9.2 percent of undocumented immigrants and 15.7 percent of documented immigrants had been told by a doctor that they had diabetes, compared to 6.7 percent of U.S.-born citizens.

Pairing poverty with higher risk jobs puts many undocumented persons at a much greater risk for health problems. Poverty alone has been linked to an increased risk of high blood pressure, high cholesterol and diabetes.

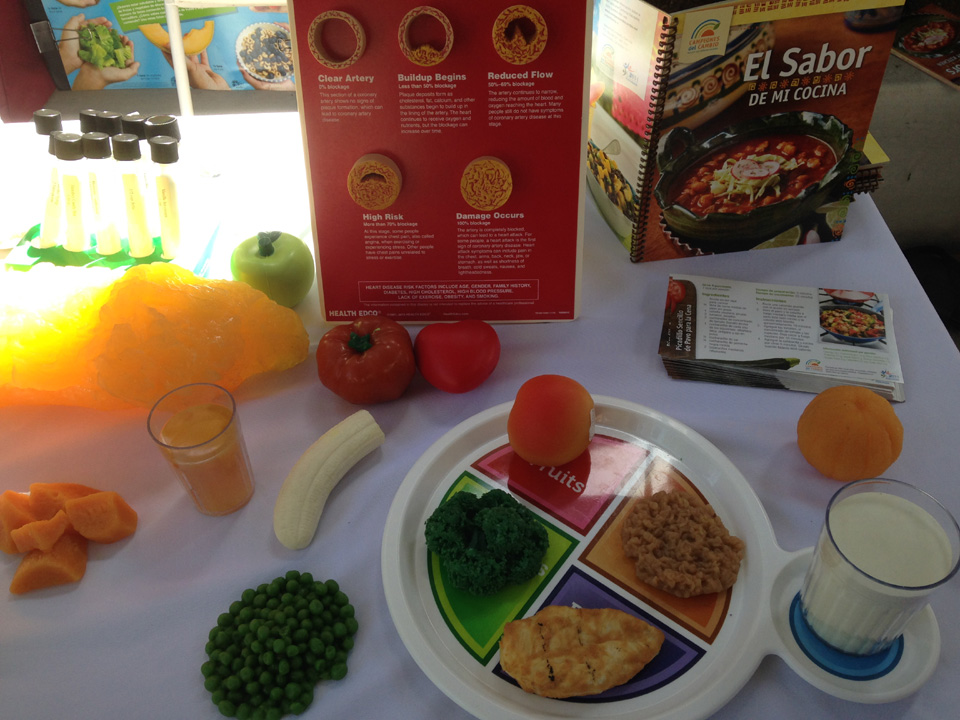

“Eating healthy has become a privilege,” Cabrera said regarding the carwash workers he represents. Cabrera said he’ll often see them eating chips, cookies and other high-processed foods.

Cabrera said many of the carwash employees don’t have access to a refrigerator at work which makes it difficult to keep healthier foods fresh.

For Victor, fruits and vegetables are almost void from his diet.

“Sometimes I buy papusas or tamales or burritos (from a truck),” Victor said when asked what he normally ate. “I eat everything. Chicken, fish, meat, tacos, enchiladas, all of it.”

For many carwash employees who arrive to work at 7:30 a.m. and have to leave their homes as early as 5 a.m., buying processed or fast food is often the easiest way to get lunch.

Poor diet paired with lack of access to preventative medical care can have dire consequences.

“Lots of diseases are preventable,” said Marisol, a volunteer with Providence Medical Center and a senior at UCLA who did not want to give her last name. “But most people don’t have access to a clinic.”

That is where services like the health fairs come into play. Providence Medical Group is one of many medical groups that help sponsor community health fairs in local churches. In addition to cholesterol and blood glucose testing, patients can undergo a bone density scan and mammogram.

Patients are first weighed and then measured in order to determine an approximate BMI. They are then handed a yellow sheet that outlines what a healthy diet consists of and what foods to avoid eating too much of. Outside are tables with representatives from different health organizations — the Alzheimer’s Association, the National Kidney Foundation, the American Cancer Society and more. Tables provide information in both Spanish and English about health problems that often go undiagnosed and untreated not only in immigrant communities but in minority communities across America.

But while eating more fruits and vegetables is good for one’s health, those responsible for getting the produce to America’s dinner plates, along with millions of other undocumented workers in the U.S., still remain at risk of unjust working conditions.

“It’s a matter of how the labor market is nowadays,” Cabrera said. “Health and safety is just not made a priority.”