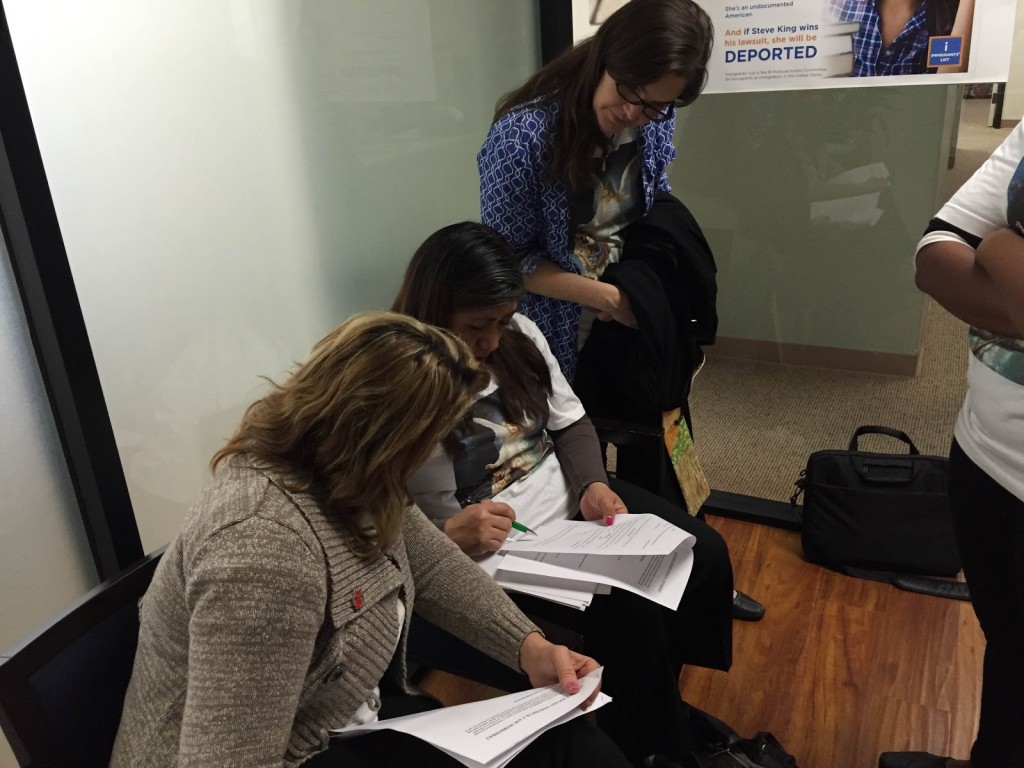

From left to right: Rev. Marta Moscoso, Rev. Maria Paiva and Rev. Heidi Worthen Gamble gather and review their notes from court afterward. The women are wearing the Guardian Angels T-shirts.[/caption]

The small courtroom was at the end of a short, gray hallway of the Los Angeles Immigration Court. The judge — the Honorable Frank Travieso — sat on his bench, a raised desk with a small microphone directly in front of him. At one point, he spoke in fluent Spanish to one of the children about school.

Since court proceedings must be in English, Travieso could not speak directly to them in Spanish during the official proceeding. To his left sat a translator, at a slightly lower level, leaning toward the small microphone on her desk. She often smiled at the children, and their parent or guardian if they had one present, as she translated the proceeding for them.

Travieso faced six rows of benches, three on either side of the small room. On these benches sat family members of the children — mothers, brothers, fathers and sisters — who were accompanying their loved ones.

In this courtroom, the only plaintiffs appearing for court cases that day were children — some in their early teens, others whose feet didn’t yet touch the floor from the wooden bench where they sat waiting.

A girl and a boy both had to miss school that day to appear in court. While most of the children spoke English, the hearing was held in their native language — only Spanish. The children wore large over-the-ear headphones that were wired to the woman translating Travieso’s words to Spanish.

A young girl showed up with her mother. The facts of her case had to be checked. The girl was in court that day with her biological mother, however the court records showed the name of another person as her custodian, a name that neither the girl nor her mother recognized.

This is the type of confusion that Guardian Angels watch out for when they go to court.

Guardian Angels is organized by a larger interreligious, interethnic organization called CLUE, which stands for Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice. The project trains volunteers to understand the legal process of immigration cases so that they can then sit in on court hearings and identify any possible violations and inconsistencies to the children’s rights.

Guardian Angels is one of many religious and nonprofit organizations fighting for the rights of the thousands of unaccompanied minors caught crossing the U.S. border in recent years who are now facing deportation. Many were fleeing violence in Central American countries, according to an April 2015 Migration Policy Institute report.

“Not once has a deportation been issued when a Guardian Angel is present,” said Rev. Heidi Worthen Gamble, a minister of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A). “We think this is because we are holding the courts accountable.”

Worthen Gamble sat in the courtroom that day with two other women ministers: the Rev. Maria Paiva and Rev. Marta Moscoso from the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. They all wore white shirts with screen images of a guardian angel.

These women come from different Christian denominational backgrounds. They take notes for each child and then send this information to the National Lawyers’ Guild for review and records.

“(The Guild) is using it for a legal suit with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) about providing legal representation to the children,” Rev. Alexia Salvatierra, a Lutheran pastor for the Southwest California Synod, explained.

Salvatierra and Paiva, the Hispanic Ministries director of the Southwest California Synod, founded the Guardian Angels project. While the Lutheran Synod is the parent organization collaborating with the National Lawyers Guild, now many different religious congregations participate.

By showing up at court cases always wearing the same shirt, volunteers seek to reach recognition from the judges who, with time, will know that Guardian Angels are visiting the hearings to make sure every child is treated fairly and equally.

“We have shared instances where a child was given shorter time than an adult would be in that context and where a child or adult was inappropriately threatened with deportation,” Salvatierra said.

Few children appearing in court that day had legal representation.

Representation Matters

Children without lawyers are much more likely to receive removal orders than children with lawyers, according to the Migration Policy Institute and data Syracuse University compiled.

The U.S. government has deported 90 percent of children without legal representation every year except 2013, according to the Migration Policy Institute report. This April 2015 report, “Unaccompanied Child Migration to the United States: The Tension Between Protection and Prevention,” discusses why unaccompanied minors are coming and the issues the surge has created for enforcing immigration policy.

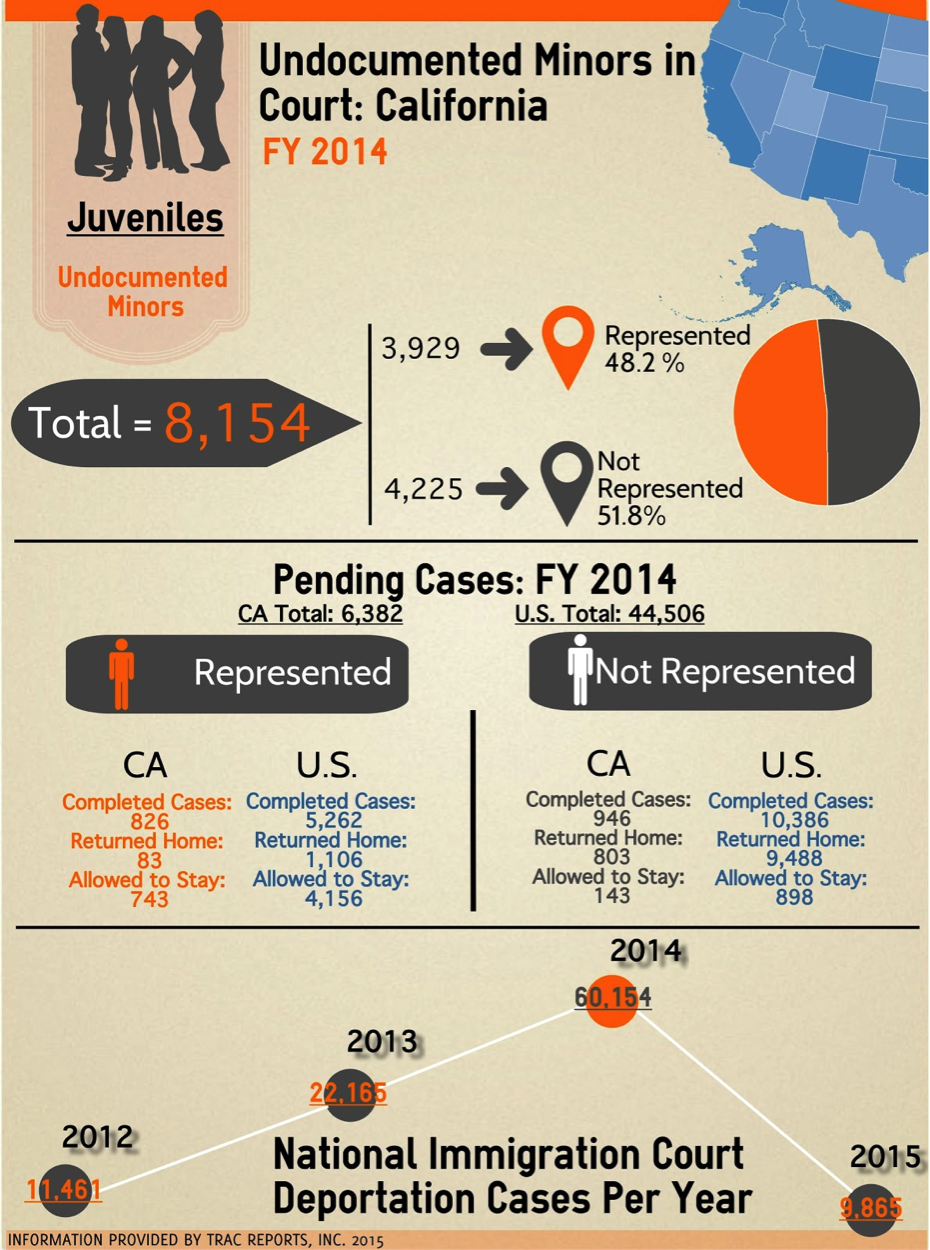

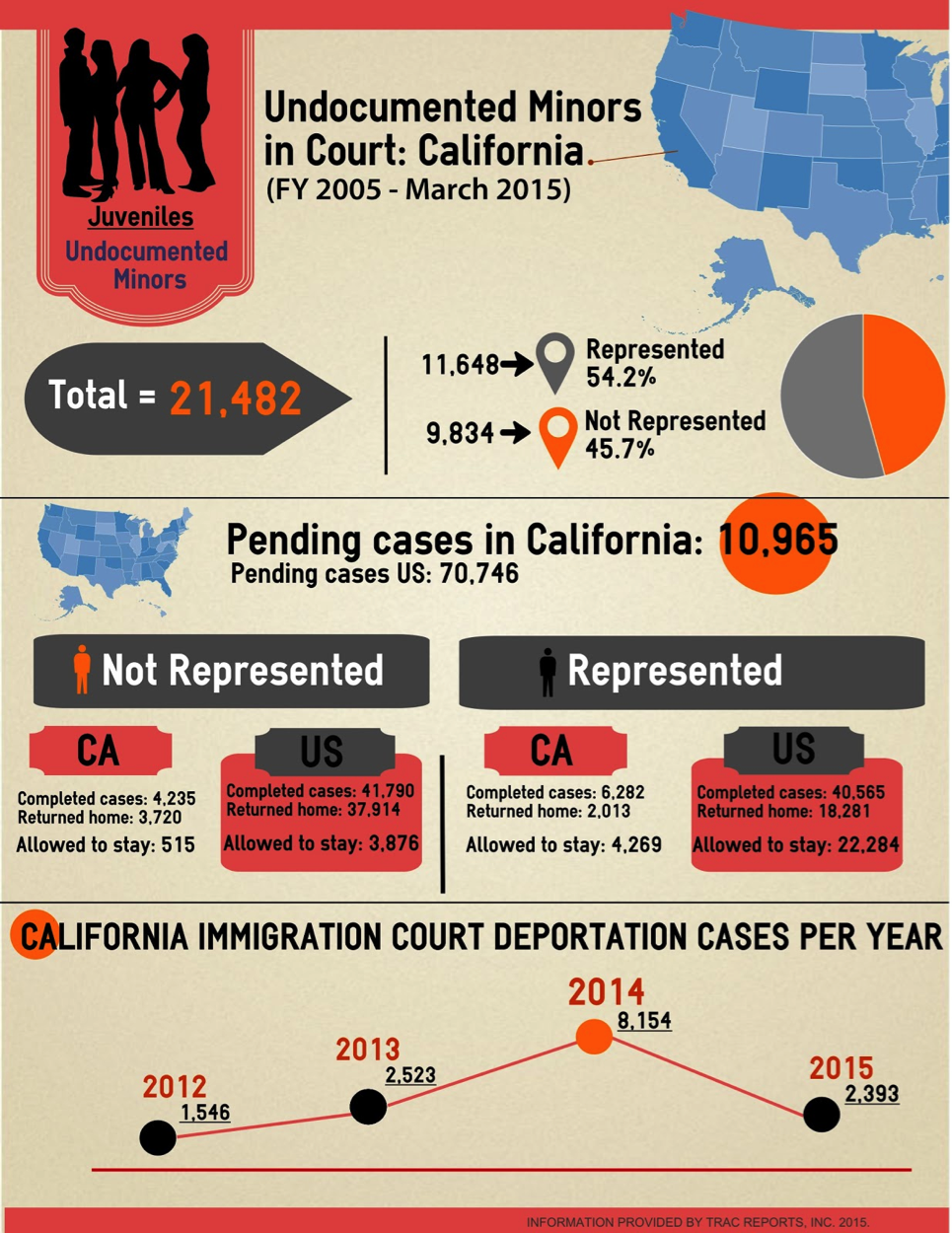

Roughly 8,154 minors underwent deportation hearings in California in 2014. More than 78 percent of the cases are still pending. Of the cases that judges decided, 50 percent either voluntarily returned to their home country or were given removal orders, according to Syracuse’s data. The government allowed the other half to stay.

When broken down by representation or no representation, the numbers are polar opposites. Roughly nine out of 10 kids with lawyers get to stay. Nearly that many without lawyers get sent home.

It looks bleak nationally too, where a total of 60,154 minors underwent deportation hearings in 2014. Of these minors, 21,966 have legal representation (36.5 percent) while 38,188 do not (63.5 percent). Roughly three out of four cases are still pending.

In the cases decided where the children had lawyers, judges ordered 780 minors removed, 326 departed voluntarily and 4,156 were allowed to stay. However, for those children without lawyers, a total of 9,215 were ordered removed, 273 departed voluntarily and 898 were allowed to stay.

That means children without lawyers are 4.3 times more likely to be sent or go home than children with lawyers.

Nongovernmental organizations advocating for UACS in court

The difference between being represented and not being represented for these children has led the American Civil Liberties Union to sue the federal government for failing to provide children with a fair trial and for lack of legal representation in immigration court proceedings.

The ACLU, along with the American Immigration Council (AIC), Northwest Immigrant Rights Project, Public Counsel, and K&L Gates LLP filed J.E.F.M. v. Holder in July 2014, according to the AIC website.

This nationwide class-action suit charges the U.S. Department of Justice, Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Department of Health and Human Services, Executive Office for Immigration Review and Office of Refugee Resettlement with violating the Fifth Amendment’s due process clause and the Immigration and Nationality Act’s provisions requiring a “full and fair hearing” before an immigration judge.

Their lawsuit calls for the federal government to provide legal representation so that immigrant children get a fair day in court.

Religious organizations, like Guardian Angels, are supporting this lawsuit as well.

“I don’t think that anybody should have to go through immigration court without an attorney and so that’s why I’m so very glad to be able to find children quality representation,” said Andrew Avorn, a litigator with K&L Gates in New York. “This is one of the most important civil rights issues that we’re facing in our country right now.”

Avorn’s law firm works with KIND, Kids In Needs of Defense, an NGO that partners with dozens of firms to provide pro bono representation to UACs. Avorn has been doing pro bono work for UACs since 2010.

Why They Come

Avorn said violence is the primary motivation for children to flee and make the dangerous journey to the United States.

Angelina Jolie and the Microsoft Corporation established KIND in January 2009 to help provide legal aid for the incoming children.

Communication Director for KIND Megan McKenna explained that the Northern Triangle — El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala — does not offer children much protection and have minimal child welfare systems.

“If these children are abandoned or fearing violence, there’s no where that they can go,” she said.

The United States may be to blame for causing the violence, gangs and drugs that are ravaging Central American communities and sending their children fleeing north.

The April 2015 Migration Institute Report (MPI) report titled “Unaccompanied Child Migration to the United States: The Tension Between Protection and Prevention” attributes the outpouring of violence in Central America to the United States’ involvement in arming these populations during the 1970s and 1980s, when civil wars broke out in the region. Following this, the U.S. government began to deport gang members to the same region increasingly in the early 1990s. Between 1993 and 2013, MPI’s report states, the U.S. government deported 254,752 criminals, sending thousands of convicted criminals directly to the Northern Triangle.

This history of civil war and criminal deportations has led to the violence and political and economic instability that is pushing UACs to the U.S. today.

Before the Guardian Angels visited court, they also attended a meeting CLUE hosted that met at the offices of the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles in Echo Park.

The honored guest at the meeting was a Roman Catholic Priest from Mexico, the Rev. Alejandro Solalinde, who flew in from Oaxaca to support the efforts of religious organizations advocating for undocumented Latino immigrants.

“Intervention of the United States in Central America has been disastrous,” Solalinde said through a translator. “The military dominance of the United States in Central America has created a lot of suffering.”

In countries like El Salvador, gangs have united and increased their influence and authority within the country so much that, even in developed regions, they have managed to threaten governmental authority and operations, Solalinde said in his speech before concerned clergy.

“The 13s and the 18s (Mara gangs) joined and today they collect more funds than the government itself,” Solalinde said.

KIND has heard the same stories from the children they represent.

“These are children who tell us how they’re being threatened by the gangs, they’ve had family members attacked or even killed by the gangs,” McKenna said.

The gangs have gained so much power and dominance in indigenous and impoverished regions of the Northern Triangle that many have outmaneuvered the weak police systems and managed to take control of entire communities. These gangs target the children in the community that refuse to join them.

“We’ve heard time and (time) again (the) saying … ‘we don’t have a choice, it’s flee or die.’” McKenna said. “So they see their only hope as coming to the United States.”

U.S., Mexican and Colombian drug policies have been central in creating the violence the children are fleeing from, Avorn wrote in an October The Blog post titled “Why They Come: The Real Reason for the Surge of Unaccompanied Children in the United States.”

***

McKenna also emphasized that gender-based violence is causing girls in particular, to flee to the U.S. in numbers unseen before the summer 2014 surge. She explained that the majority of girls fleeing to the U.S. are sexually assaulted on the journey, but are in such desperate conditions in their home countries that they are still willing to face the risks.

“That’s not the kind of thing you do for a job, you know, nobody undertakes a 60 percent chance of getting raped so they can go get a job somewhere, that’s absurd and it’s offensive when people suggest otherwise,” Avorn said.

To read more about Avorn’s work with UACs click here.

***

Avorn said that economically and political instability add to the rising violence.

“These are some of the most underdeveloped countries in the world,” Avorn said of the Northern Triangle.

Economically instability leads to political instability.

“Those countries don’t have governments like we have governments,” he said.

Without stable economies and governments, the violence will continue and children will continue to attempt the dangerous journey to the U.S., hoping for safety and security.

Children who flee to the U.S. typically already have parents or other relatives who have entered before them. At least 85 percent of Central American UACs that are apprehended at the border have parents or close family members in the U.S., according to the MPI report. These relatives send remittances back to care for the children. This money is often used to help fund their migration north.

KIND Abroad: Advocacy After Deportation

KIND is also working to help the children who do get deported back to unstable situations.

KIND launched the Guatemalan Child Return and Reintegration Project in 2010 as an experimental three-year program. It is still in existence today and KIND hopes to expand the work it is doing, McKenna said.

The Guatemalan program works to provide deported children with safety and opportunities in their home countries. They partner with The Global Fund for Children and other local NGOs, to provide skills training, counseling services and educational resources, McKenna said.

“Not all of them want to leave their home country — I think it’s a myth that they want to come to the United States no matter what,” she said. “There are a number of these kids that want to stay in their home country but they don’t feel safe.”

McKenna said the program has been very successful: “A large majority of children who we’ve worked with have stayed in their communities.”

She explained that part of their continuing advocacy work is to get the U.S. to fund more programs in the region, specifically that support child protection and welfare.

The MPI report regarded KIND’s Guatemalan program as one of the most promising programs in the Northern Triangle that is working to support and reintegrate UACs deported back to their home countries. It recommends that the U.S. monitor successful programs, like the Guatemalan program, and provide them with funding.

The growing tide of Central American UACs

MPI projects the continued tide of incoming UACs will be lower than the summer 2014 high, but still higher in comparison to previous years, based on data from the U.S. Customs and Border Control.

There were 52,000 UACs apprehended at the border who originated from the Northern Triangle in 2014, but MPI projects that only 39,000 children will be apprehended from all countries this year.

Religious organizations advocating for UACs in Court

Meanwhile, religious organizations try to make sure children have an angel in court, and that their congregants are informed.

One of the women representing Guardian Angels in court is the Rev. Marta Moscoso. Moscoso migrated to the United States about 20 years ago. She lost her family during the Guatemalan Civil War before fleeing to the U.S. She began her life anew in Los Angeles as a Lutheran pastor.

Moscoso’s church, Faith and Hope Lutheran, is in South Gate, a community that is 95 percent Latino and located 12 miles southeast of Downtown LA. Many of the residents are undocumented, Moscoso said.