Long or short hair.

Green or brown eyes.

Yes to tall guys.

Black but never Asian.

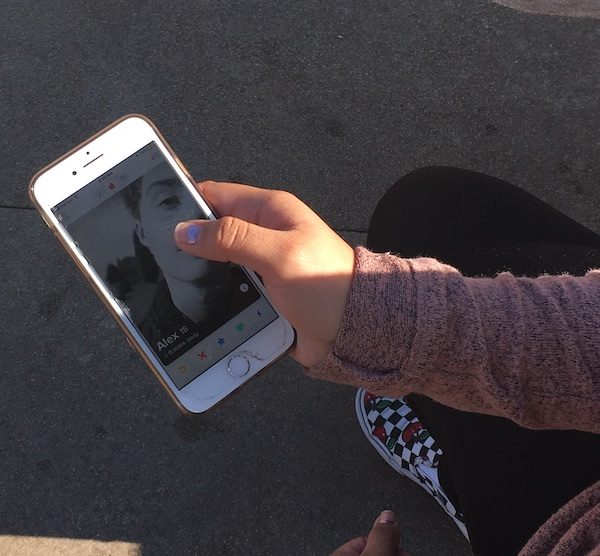

When it comes to romance, everyone has an idea of what characteristics they’re attracted to but when does having a “type” become racist?

Comments that are nonchalantly tossed around like “I don’t do Asian guys” or “Black girls just aren’t my type” reinforce the fact that many people evaluate potential partners solely based on race or ethnicity, rather than their whole person. These remarks and the sentiments behind them invite heated debate as to whether racial and ethnic preferences in dating are latent discrimination.

“There is such a big pressure to be politically correct in our society,” Interpersonal Communication Professor Sarah Ballard said. “The idea of taking a step back and considering, ‘Do I have any intrinsic biases?’ is such a threat to people.”

Several factors come into play when looking at racial and ethnic preferences in dating, including upbringing, cultural barriers, racial tension and stereotypes, as well as media representations of ethnic groups.

The situation at Pepperdine

Despite a somewhat diverse student body, as well as various intercultural programs, interracial or interethnic relationships seem to be a rarity on Pepperdine’s campus. Jaibir Singh, a junior film studies major, thinks that it is because people are too comfortable in the racial or cultural groups they identify with.

Likewise, Ballard said she’s noticed only a few interracial or interethnic relationships and that she’s talked to many students who have struggled to maintain these relationships. There are two main factors that Ballard said contributes to this: for one, Pepperdine is not the most ethnically diverse place and people tend to gravitate toward those like them, meaning cultural groups don’t mix enough. Ballard said a second factor is that while there have been strides to hire more diverse faculty, professors are still mostly white, meaning that students don’t see diversity modeled in the structure of the university.

A Pepp Post survey of 90 Pepperdine students found that slightly more than 67 percent have types to assess whether individuals are dating material. Of those that have a type, 48 percent have a type that takes race into account and roughly 41 percent think having a racial preference in dating is racial bias.

Upbringing and cultural differences shape perspective

Families significantly shape children’s views on race and relationships. Cultural and race distinctions are often passed down from generation to generation. Family is the first institution that people go through and learn values from, Ballard said.

“As a kid, I was taught that America is a giant melting pot and that was meant to be a good thing,” Ballard said. “But what that insinuates is that when you come to the United States, you have to melt; you don’t get to keep your own identity, rather, you have to mix. This idea alienates people and ignores that fact that color and culture matter.”

Certain ethnic communities, such as Korean or Indian cultures, exert immense pressure on individuals to date or marry within that community, demonstrating the significant role that family values play in how individuals choose partners.

“Coming from an immigrant family, I saw this with my own parents,” Intercultural Communication Professor Charles Choi said. “Their preference was certainly for me to marry a Korean woman. A lot of it had to do with wanting to have an addition to the family that didn’t present language or cultural barriers and allowed for a more cohesive experience.”

Growing up in an Indian household, Singh said it’s hard for foreigners to readily adapt to Indian society, which is very tight-knit. Because of this, he said his parents would oppose him marrying outside their culture.

Ballard said dating interracially or interethnically entails a different level of commitment because it requires an individual to like or love someone enough to fight for their right to date them amid pushback from family.

“You’re not just marrying a person, you’re marrying a family,” Choi said.

Sophomore English major Danielle Aro experienced this firsthand. Aro and one of her classmates began speaking and she could tell that he was interested in her. He eventually began acting different, so she asked what was wrong.

“In a nutshell, he told me that this — us — wasn’t going to work because of our cultural differences,” Aro said.

Despite Aro showing interest in his culture, he later told her that he would connect better with someone from his own culture.

“I’ve never experienced anything like it,” Aro said. “I’ve had relationships end but none of them were because of cultural differences. I felt hurt and offended.”

The poll showed that about 32 percent of students feel pressure from their community (e.g., friends, family, church, etc.) to date people within their ethnic group or race.

Because of the strong community influence that attaches itself to those from groups with strong identities, racial preferences are more apparent in long-term relationships than they are in short-term relationships or hookups, Elizabeth McClintock and Velma Murry wrote in a 2010 article published in the Journal of Marriage and Family. Students desire greater similarity in long-term relationships than in hookups because having a same-race or same-culture partner increases compatibility and acceptance among parents.

Ballard said that research on intercultural relationships highlights four primary ways couples can negotiate culture. When starting a family, a couple can choose to do one of the four: emphasize important aspects from each of their cultures, fully integrate their cultures, ignore cultural differences or unwittingly have one person’s culture dominate and overlook the other’s culture. Ballard said that some of these methods can be more difficult on one partner because they feel that they’re giving up a part of themselves to maintain the relationship.

Olivia Robinson, a junior integrated marketing communication major, grew up in an interracial family, so race and ethnicity in terms of who she dates aren’t points of contention for her family. She doesn’t think that cultural differences need to be as big of a barrier as people may think.

“It’s an opportunity for growth and cultural exchange,” Robinson said. “It doesn’t need to be a point that holds the progress of an entire relationship back.”

Robinson said interracial relationships are often looked at through a lens tainted by stigma based on institutionalized messages of exclusion and damaging tropes.

“Some people have a problem with interracial relationships because they think that birds of a feather should flock together but who says a bird can’t be multicolored?” Robinson said.

Long-held racial tensions and damaging stereotypes

In addition to family influences, certain cultural traditions and race relations are formed through historical conflicts between certain ethnic groups.

For example, despite the Supreme Court’s 1967 ruling allowing marriage between whites and blacks in the case of Loving v. Commonwealth of Virginia, the concept of interracial relationships remains controversial long after declared legal because of America’s history of slavery and uneven power distribution, Carolyn Field and her colleagues wrote in their 2013 article published in the Journal of Black Studies.

Junior political science major Payton Silket said the countless toxic stereotypes attached to the black community, such as being too ghetto and having issues with drugs, alcohol and abusive behavior, reinforce negative perceptions that other races have of black people.

From experience, he knows that in many places, just being black earns him an automatically assigned persona based on these perceptions. He said that these stereotypes unjustly discredit the black community and discourages others from giving them the benefit of the doubt in both the dating scene and society in general.

“I believe there is an element of racial bias,” Silket said. “Whether based on physical characteristics or cultural norms, when people choose not to date someone because of those preconceived judgments, they don’t give others a fair opportunity to prove those stereotypes or judgments wrong.”

Karina Valenzuela, a sophomore public relations major, said it’s often the case that on campus, guys see her as an opportunity for a good hookup because she’s a “fiery” Latina and has a curvy body type. She said this isn’t a compliment or form of respect because they dismiss her as long-term dating potential based off a stereotype.

Although layers of historical context and unfavorable stereotypes can foster unhealthy race relations, the treatment a group faces within society has different implications for members within that group.

“Different racial and ethnic groups experience life differently in this country,” Choi said. “We have a tendency to want to be with someone who has a shared experience.”

Choi attributed this tendency to reinforcement theory, the idea that people are more likely to choose people that will reinforce their worldview. So while stereotypes may marginalize certain groups, they can also act as a bonding factor between people in those groups.

Physical feature categorizations also factor into damaging perspectives on racial and ethnic groups. Eurocentric beauty norms, such as lighter skin tones and certain physical features, apply more strongly to women than men, Kate Strully wrote in a 2014 article published in the American Journal of Sociology. This ideal of feminine beauty introduces more barriers to interracial dating for black women and may partially explain why most black and white interracial relationships involve black men and white women instead of black women and white men.

The interactive photo above uses data from a 2014 OkCupid study to describe how dating site users rate certain races (Image courtesy of Christian J. Park).

Media representation

The portrayal of a culture in the media can greatly impact what characteristics are attached to that group. Silket said hypersexualization regarding black men has a lot to do with media roles that create standards for what a “real black man” should be, e.g., tall, strong and having large genitalia.

“Life imitates art,” Silket said. “These roles perpetuate the idea that black men are good for sex but not good partners for life. That’s when they become a sexualized token instead of a human being.”

Black males reported white women seeing them merely as objects of “sexual novelty” in McClintock and Murry’s article. This explained, in part, why black men are chosen more frequently for hookups than for long-term relationships by other-race partners.

McClintock and Murry’s reports also showed that white students fetishized Asian women. These fetishes can be traced back to media portrayal of Asian women as submissive, often occupying roles as prostitutes or sex slaves.

Silket said that shows from the 1970s to the 1990s, such as “Good Times,” “The Proud Family” and “That’s So Raven” showed black families in a positive, multidimensional light. He noted that popular contemporary shows endorsed by black-owned networks and audiences like “Empire” or “The Real Housewives of Atlanta” shift the positive narrative emphasized in older shows to one side of black culture furnished with gangsters, scandal and familial instability that back up the ghetto or “ratchet” identity frequently associated with black people.

“It gets dangerous when people fail to realize that it’s just entertainment and not the whole picture,” Silket said.

Choi said that when movies go beyond stereotypes, like Black Panther and Crazy Rich Asians, that effort is celebrated because they free groups from singular stories that don’t accurately represent them.

Valenzuela said roles in shows and movies need to be diversified. As a Latina, she noted that Latinos in the media are always sexualized. She thinks that expanding their roles will result in more multilayered Latino characters who bring more than sex to the table and more accurately represent the Latino community.

Solutions?

While not everyone agrees on racial preference being racial bias, most people agree that excluding an entire race as dating potential treads on dangerous territory. Ballard said one thing that might help combat factors that negatively influence preference and invite exclusion is demanding our political leaders engage in inclusive civil discourse and creating more spaces to speak about race and culture openly.

“If you can’t talk about it,” Ballard said, “how can you learn or grow?”

Another simple solution that most people agreed on is understanding that while culture does impact character, an individual’s story goes beyond their color and any stereotypes attached to it.

“Consider that love really is blind,” Robinson said. “Personality is not bound to race or ethnicity. At the end of the day, if you love someone, you’re not going to care if the race or culture that they’re from isn’t what you’re used to and you’re not going to let inaccurate media depictions conceal their truth.”

Angel Thairo completed the reporting for this story under the supervision of Dr. Christina Littlefield and Dr. Theresa de los Santos in Jour 241 in spring 2018. Dr. Littlefield supervised the web story and Dr. de los Santos supervised the video package.