When Lily Castro, the 49-year-old Salvadoran behind Lily’s Malibu, came to the U.S. 30 years ago, she said her life was one big fill-in-the-blank. There was one thing, however, that she knew with certainty. “I wanted to be successful,” Castro said. “That’s why we all want to come to the US, right?”

Castro, like many others, immigrated to the United States with a purpose. “The American Dream,” Castro said matter-of-factly. “That’s why I came. I have always loved cooking and I always dreamed of owning my own business.” Her popular restaurant, Lily’s Malibu, stands, 30 years later, as palpable proof of a dream fulfilled.

The journey to success, she said, was all but simple.

“I used to work 14 hours a day when I started. Nothing comes easy,” Castro said. “It shows [immigrants] that we are meant to come here to work, to fight for what we want. We don’t come to use up benefits; we come to work. It takes hard labor, and effort and great sacrifice.”

Castro’s relentless perseverance, she described, eventually provided her with greater financial stability which, in turn, allowed her to help others around her. She supported her family here and her mother back in El Salvador and contributed to her community in Malibu, to the employment of other immigrants and, yes, to the U.S. economy.

Castro’s story is a bite-sized model for a trend that spans the entire nation: immigrants are an increasingly significant part of the workforce in America.

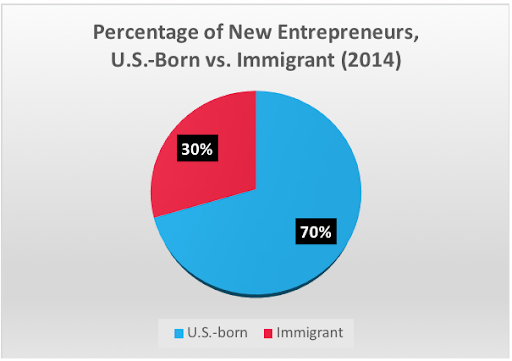

A haven for those in pursuit of “The American Dream,” the U.S., unsurprisingly, attracts millions of foreign-born entrepreneurs each year, with one in every five entrepreneurs in the country being, in fact, not native-born. Immigrant entrepreneurship has for years represented a substantial contribution to the US economy, creating about a quarter of new businesses in the United States, according to an article published in Forbes in 2018. The restaurant industry is one business where many nonnatives often find their new home.

Cholada, Lily’s Malibu, Nicolas Eatery and Taverna Tony are all mainstays in Malibu, they were all founded by immigrants, and they all stand today as nearby illustrations of immigrant entrepreneurship.

Immigration in the U.S.: The Numbers

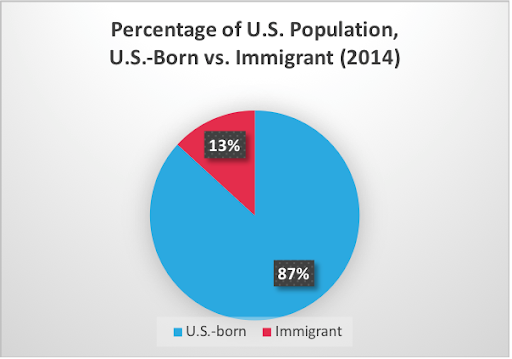

According to the National Immigration Forum, immigrants are more likely to start businesses than those born in the U.S.

A study published by New American Economy in March shows that the millions of hopefuls flocking into the United States from around the world every year are prepared to work for their success, evidenced in the 3.2 million immigrants that ran their own businesses in the U.S. in 2017.

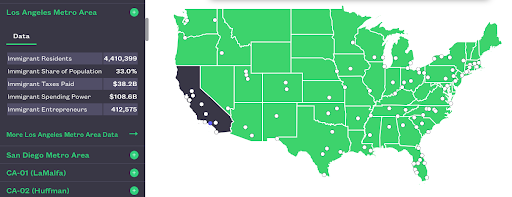

California is the leading state in immigrant entrepreneurship, with one third of its small-business owners being immigrants. One need not look too far to see this phenomenon at play. Several of Malibu’s most beloved community staples are, in fact, owned by non-Americans who have found their home in this little corner of Southern California.

Such was the case for Tony Koursaris, founder of Malibu’s Taverna Tony.

“I came to America because of a dream,” Koursaris said. “America is the land of plenty, the land of opportunity, the land of freedom. If you are really honest about working hard, you can achieve anything in America.”

His restaurant, which he calls “a dream come true,” opened in 1994 with the purpose of showing locals “what Greeks are really like.” Koursaris said he had many Greeks come to his restaurant over the years, saying “they found home away from home.”

For senior Advertising major Anastasia Matty, a second-generation Greek-American and one of Tony’s loyal customers, Koursari’s restaurant was precisely that. She found in it much more than spanakopita and baklava and avgolemono; she found in it, she said, a sense of home. “It reminds me of Greece,” Matty said. “It reminds me of the food my grandma makes at home.”

Koursaris said he believes food is a large part of cultural identity. “I built the restaurant as testament to my culture and my country and to the love I have for Greece and for America,” Koursaris said.

Taverna Tony gave Koursaris a platform from which to build community in his host country while simultaneously showcasing his native culture. His medium of communication was the universal – and fundamentally human – language of food.

“If you don’t know how to eat, you don’t know how to love,” Koursaris said.

Food: A Currency of Culture

Everyone needs to eat.

Limiting food to a merely transactional necessity, however, would be nearly iniquitous. Food is a means of communication and celebration, and an essential part of culture and identity.

Senior Psychology major Alisa Wakita, a first-generation Japanese-American, said food is an important part of her cultural identity. “Eating together is important for my family,” Wakita said. “It’s an integral part of how we bond.”

For Wakita, Japanese food is more than rice and gyozas; it is a feeling of home. She is part of the Japanese Student Union at Pepperdine and says food is a key component of how the club tries to build community on campus.

“In the past, we’ve actually worked with the caf to put on a Japanese food day,” Wakita said. “We also did a sushi-making night and taught people how to make sushi at the Lovernich Commons.”

Food is a catalyst for the creation of relationships because it is both a form of communication and a pivotal component of individual- and collective – identity.

“One of the most common ways we use food is the construction of our personal identities,” Nevana Stajcic wrote in “Understanding Culture: Food as a Means of Communication.”

“Identity cannot be performed in isolation,” Stajcic said. “We must think and understand identity through our relationships, our communicative practices and interactions with others.”

There is something to be said, then, for immigrants who bring their food and their cultural identity to a new place. It is a form of communication, a way of building and reshaping a collective identity through interacting with others.

French-born Nicolas Fanucci, owner of Nicolas Eatery in the Malibu Sands Center, is bringing his cultural and personal identity to the table. Unlike Castro and Koursaris, however, he is doing so with his entire family. The restaurant is made to feel like their family’s kitchen to create a sense of community.

“We designed [the restaurant] and we made it based on what we do at home,” Fanucci said.

The Fanuccis invite the people of Malibu to take part in their family traditions and feel at home. The community, he said, has been exceptionally supportive.

Sawai Theprian, owner of Malibu’s Cholada Thai Beach Cuisine, said she too derives her love for cooking from family. “I love to cook,” Theprian wrote in an email. “When I was a child, I have to help my mother to prepare food for my family.”

Theprian and her husband Nikorn Sriwichailumpan have owned Cholada since 2000, according to Malibu Magazine, .

Starting a business in a foreign country, she wrote, was anything but easy. “From the start I know little in English,” Theprian said. “I have to hire [a] professional to help me.”

Theprian, who said she considers food to be a large part of her cultural identity, wrote that Cholada has allowed her to show locals her culture and build community.

For two decades, Theprian and her husband have been serving Malibuites authentic Thai food in a home-like environment. The ever-full dining spaces are testimony to the community’s ongoing support (and, most definitely, the tantalizing fare).

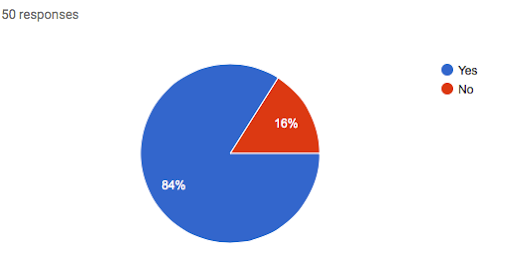

Fanucci, Koursaris, Theprian and Castro all report warm welcomes from the Malibu community which has, time and again, supported immigrant entrepreneurs, allowing them to bring the unique flavors of their home countries all the way down to Southern California.

Immigration has long been an integral part of American culture and ethos. The United States began as a country of immigrants, often given the title of “melting pot” as an allusion to the numerous traditions that have mingled on American soil, effectively giving its culture the unique character it has today.

Adam Rappoport, editor in chief of Bon Appétit magazine, wrote in his editor’s letter for the magazine’s “Generation Next” issue, “But isn’t this what has always made America great? That we are a country of immigrants, constantly inventing and reinventing?”

Rappoport subtly addresses the negative connotation that has come to characterize the word “immigrant,” but ends his letter by saying, “If you’re going to love kimchi, and all the other amazing food this country has to offer, you’ve got to love the people who make it, too.”

Maria Belen Iturralde completed the reporting for this story in Jour 241 in Fall 2021 under the supervision of Dr. Elizabeth Smith. Dr. Littlefield supervised the web version of the story.