On March 11, 2020, Pepperdine University announced the move from in-person classes to an online format, igniting stress and panic amongst professors toward the unprecedented events they were about to face.

Professors had to re-work their courses in a few days. They had to figure out how to engage with students online. They were put in situations where they felt lost and uncomfortable.

But, despite their own mental state, professors were encouraging their students every day. They may have appeared to have everything together, but they were struggling just as much.

“Every class was different,” English Professor Maire Mullins said. “Every day was different.”

Professors were also balancing these increased workloads with needing to make time for their families’ needs, all amid a global pandemic.

The emotional impact on professors

Theatre Professor Cathy Thomas-Grant said she experienced a difficult transitional period to the new Zoom format.

“My learning process was steep, steep, steep,” Thomas-Grant said. “I had five days to completely re-work my syllabus.”

Once she began teaching online, Thomas-Grant said there was not a class where she was not in tears. The transition was exhausting, she didn’t know how to fully process what was going on.

“We were in mourning,” Thomas-Grant said. “We were grieving the loss of each other’s company, I’m tearing up just talking about it.”

Thomas-Grant was also experiencing a toll on her mental health from the pain of isolation.

Between May 2020 and July 2021, she saw her son and his fiancé only three times. She also went a year-and-a-half without seeing her 85-year-old parents.

“I was anxious about everything,” Thomas-Grant said.

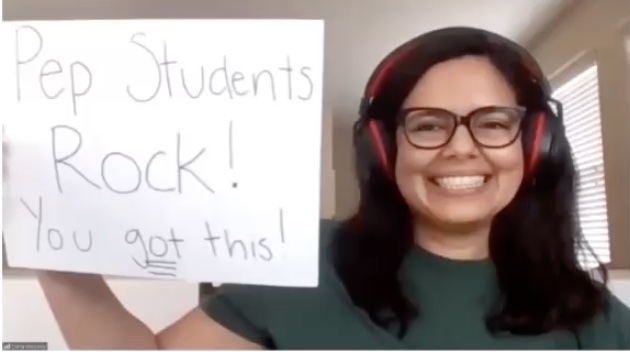

Thomas-Grant was not the only one who had concerns about the intensity of online teaching. Communication Professor Diana Martinez was shocked when she received an email that she was going to have to shift to an online curriculum due to the pandemic. She said the learning process was a “Bit of a blur, if I’m being completely honest.”

Martinez said she felt very outside her comfort zone as she began online teaching.

“I wanted to make sure I had everything together so that I could really be there for my students,” Martinez said. “And I was feeling really nervous.”

Mullins said she had an interesting experience when it came to adjusting to a teaching format she was unfamiliar with. She felt challenged when it came to learning this new format, but it was a process she learned to embrace.

“It was a journey we were all on,” Mullins said. “And I loved going on that journey with students.”

Mullins saw the positive in this experience. She enjoyed teaching material to students because she was able to physically see the emotions they evoked while reading a story. She felt excited to come to class, prepared for the unknown.

“It was incredible,” Mullins said. “It was labor intensive.”

The science of emotions

Chiconia Anderson, a psychology professor at Pepperdine’s Graduate School of Education and Psychology (GSEP), understood the struggle for professors due to her experience teaching online prior to the pandemic.

Anderson worked with professors during the pandemic to help them teach on Zoom. During this process, she saw individuals become “Zoomed out.”

Anderson referenced Pavlov’s law to explain how working remotely led to overstimulation. Ivan Pavlov illustrated how people could be conditioned to react to certain stimuli. Today, technology has conditioned people to check their phones every time they receive a notification. They have been conditioned to attend to the newest activity in front of them.

Anderson believes people began to forget to live in the moment. A lot of pressure and anxiety arises from lack of face-to-face connection.

“One of the problems we saw online is that people were totally disconnected after a while,” Anderson said.

The energy of in-person teaching was taken away online, making it harder to connect, Anderson said. Professors were unable to feed off their students’ energy while teaching online and students were unable to feed off their professors’ attitude in a class.

Connecting with students

While finding ways to make themselves feel comfortable, the professors’ main focus was on finding ways to make their students feel more at ease with the online format.

Martinez implemented many tactics during Zoom classes, one of her favorites being “Laughing Yoga.” Martinez would begin by having students pretend to laugh, and for 15 seconds, that’s all they would do. Students were able to release their frustrations and feel more comfortable about being in class that day. She wanted to acknowledge that everyone was entering class handling their own personal dilemmas.

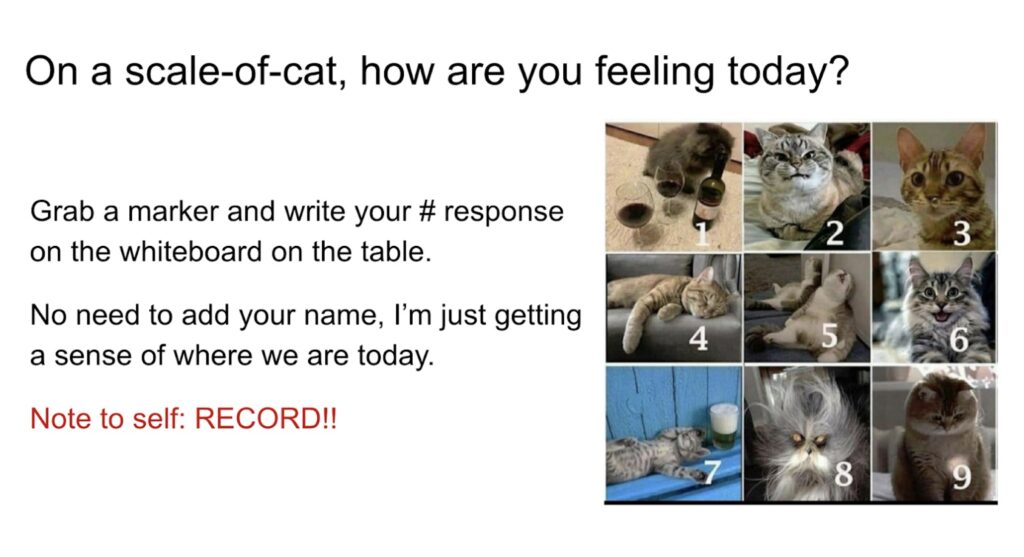

Math Professor Elizabeth Thoren connected with students by creating a poll each day and allowing students to rate their mood from 1 to 10, but with a fun twist.

Thoren created a “Cat poll” for students. She placed photos of cats on a slide and assigned each one a number. She then asked students to vote on a Zoom poll which cat was their mood for the day. Thoren still uses the poll in her in-person classes today to create community

“Let’s just acknowledge that every student in this class brings everything going on in their lives with them,” Thoren said.

Mullins also implemented mental health check-ins for students at the start of each class. With her “one-word check-in,” Mullins asked her students to provide one word to describe how they were feeling. Students had the opportunity to elaborate or they could simply leave it at the one word.

This provided her students the opportunity to be open with her on how they were actually doing each day. If there was a majority of the class not feeling their best mentally that day, she would cater the class to allow for students to have an easier learning experience.

Katelyn Romeike, senior business administration major, said her professors did great jobs providing the best learning experience possible.

“COVID was a very hard time especially in the learning environment,” Romeike said. “And I had a few professors, specifically Professor [Amy] Johnson, schedule one-on-one meetings with us outside of class to really make us feel comfortable and connected to her.”

Romeike believes that her professor’s effort toward connecting with students really encouraged her to work hard throughout the semester.

Parent to professor

Teaching is not the only job professors have, as they have research and service requirements. Many professors are also parents.

Scholarly-single mindedness is extremely difficult for professors who have children due to the overwhelming demands from both their job and serving their children, Maggie Doherty wrote in a September 2021 Chronicle of Higher Education article. Doherty found that professors would put off having children until they could get settled into their job. By doing so, it would give them the ability to pour all their attention into their work and students.

Yet during the pandemic, the jobs of parent and professor overlapped as schools shut down. In addition, more than half of the nation’s childcare facilities were shut down due to the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a July 2020 Study of Early Education in Louisiana.

Martinez is a professor and a mother. At the start of the pandemic, she had to balance raising her children, especially her 7-year-old daughter, while also teaching her college courses. Her daughter started the first grade via Zoom, and Martinez had to help her daughter learn how to navigate the online classroom.

She found it difficult trying to devote time to her daughter and students. There were moments where she needed to switch her mental focus from first-grade parent to college professor each time she entered a Zoom class.

“Given the constraints in the family household that meant that I needed to be in Zoom school in a first grade class for a certain amount of time and then join my students I was teaching for a certain amount of time,” Martinez said.

She said it was interesting to watch her daughter learn because she is used to sending her daughter away to school.

Thoren was also struggling to parent while teaching online.

“Personally, I have a 6 year-old, and he didn’t have child care for a long stretch,” Thoren said.

She and her husband are both math professors and trying to find time to devote to their son and students was quite demanding since her attention was on different things all the time.

The constant switching from parent to professor was difficult. Yet, Thoren said she couldn’t believe it when she sent him to childcare for a half day in October 2020 and had a quiet space to herself for the first time in forever. She explained how weird it was working in silence, as she hadn’t had a quiet two or three hours in months.

The light at the end of the tunnel

Some professors have an optimistic outlook on online teaching. Mullins cherished her ability to see her students’ faces close-up each day in class. She believes that this experience was something to appreciate.

“You know I used to have a really negative outlook [on online teaching],” Mullins said. “But now I have a positive outlook. I feel that it can be really effective.”

Mullins is thankful for the online webinars and informational sessions that the Center for Teaching Excellence and Technology and Learning department offered, because it allowed her to develop her teaching skills in a diverse way.

“It was time well spent,” Mullins said. “It really helped me to be a better online teacher.”

Martinez said she believes that the tools used to create these online curriculums are something beneficial to her personal skill set.

“Technology can help us keep our students connected even when they can’t be physically there,” Martinez said.

The return back to campus

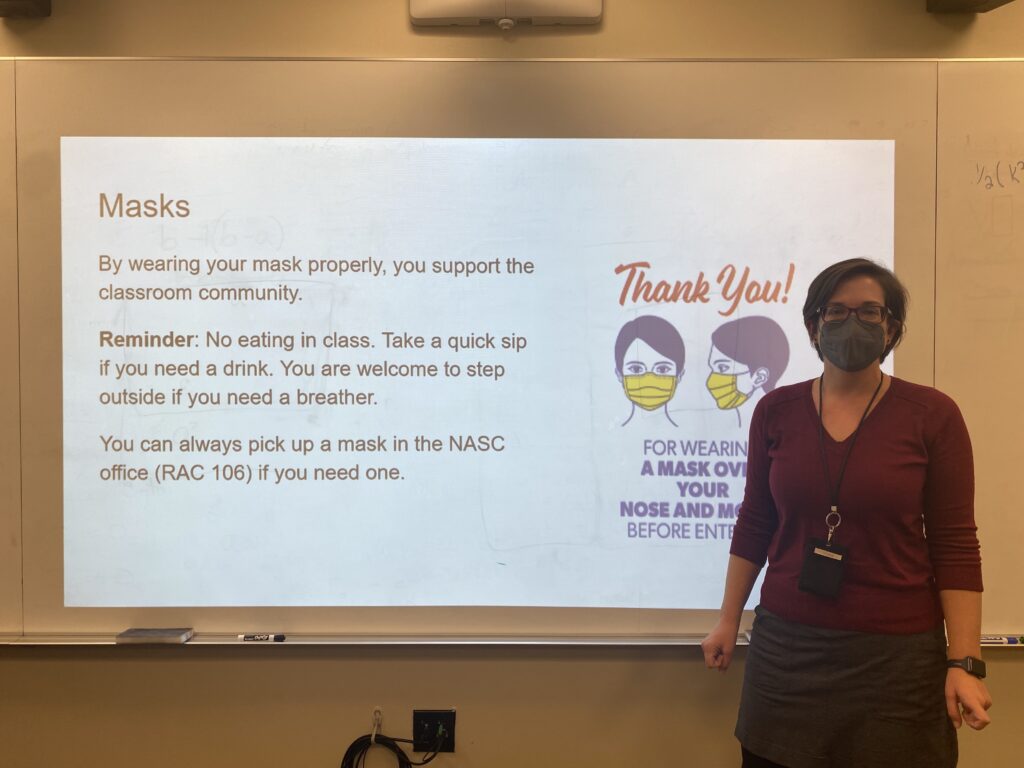

After a year of online teaching, adjusting back to in-person presented a new set of challenges following COVID-19 protocols, such as requiring masks to be worn indoors at all times.

“I think the toughest thing for faculty is that we need to be mask police,” Thoren said.

Thoren said most students actively choose to follow these protocols. She presents a slide thanking her students for wearing their masks properly.

For Thomas-Grant, it took some time adjusting after teaching online.

“It takes a different kind of energy to teach in-person,” she said.

Thomas-Grant said she was nervous the first few weeks because she felt that Pepperdine was too crowded. She did not feel comfortable being surrounded by people after being in isolation.

As time goes on, she has learned to navigate each day. She believes everyone is as pleased as she is to be in person once again.

“The blessings of being in-person far outweigh the challenges,” Thomas-Grant said.

Ale Hurtado reported this enterprise story in Jour 241 during the Fall 2021 semester under the supervision of Dr. Christina Littlefield and Dr. Theresa de los Santos. Dr. Littlefield supervised the web article.