As she enjoyed an unplanned nap at Jamba Juice, freshman psychology major Alexandra Barling missed her 10 a.m., class. Waking up at 11 a.m., she realized her mistake and rushed to her room to get a blanket before heading to her next class at noon. By that time, she said she felt lethargic and found herself randomly laughing during her religion class. Leaving class, she realized that she retained nothing and proceeded to go back to her room for another eight-hour nap. The night before Barling’s napping disaster, she spent the whole night studying for midterms and doing homework and found herself going to sleep at 5 a.m., only to wake up three hours later, severely throwing off her productivity for the entire day.

“Now I am in this terrible sleep cycle that I’m struggling to overcome,” Barling said.

Sleep deprivation is nothing new and it continues to hinder students’ ability to experience college in an optimal state. In a study published by the American Psychological Association, it was found that sleep deprivation impacts cognitive processes, reducing attentional arousal and hindering central processing. This is an issue that not only impacts the community at Pepperdine, but extends to all who struggle with sleep deprivation at the hands of a busy schedule. A Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment study reported in 2017 that as many as 60% of college students struggle with poor sleep habits.

Signs of Sleep Deprivation on Campus:

“Sleep is a quality of life changing habit,” Connie Horton, vice president for Student Affairs, said. “If people will add even just a half hour to the average amount of sleep they get a night they’ll experience better concentration, better physical health, better relationships. Sleeping is critical and students often view it as the first to go; the optional part.”

For Horton, sleep deprivation is old news. As a psychologist by training and former director of Pepperdine’s Counseling Center, the issue is often brought to her attention by students. She is experienced in helping identify the problem in her students and she offers valuable advice and resources for change, so as to reduce the damaging effect that sleep deprivation can have in all areas of their Pepperdine careers.

“Students don’t usually say ‘I have a problem with sleep deprivation,’ they just get overwhelmed and sometimes they’re slipping into a pattern of not prioritizing sleep. I think it comes up all over student affairs,” Horton said.

She said she sees the effects of sleep deprivation on campus in students who are getting sick regularly, experiencing fragility, feeling depressed, unsettled, unhappy and teary without knowing what’s wrong, lacking patience and struggling with relationships. Sleep deprivation usually accompanies these issues, Horton said

“You know there are a million things that need attention so it would be easy to say, and I would agree, it could use more,” Horton said. “We have made [sleep deprivation] a pretty big priority though over the years.”

Some of Horton’s biggest concerns with sleep deprivation are the impacts that it has on the body, mind, soul and spirit.

“Sleep loss leads to profound performance decrements. Yet many individuals believe they adapt to chronic sleep loss or that recovery requires only a single extended sleep episode,” according to a recent Harvard Medical School study,

Don’t Fight It:

It is not uncommon to hear students say they will catch up on sleep over the weekend if they can’t maintain healthy habits during the week, however, it is crucial to get the right amount of sleep each night to function at one’s best.

Dr. Nathaniel Watson, professor of neurology at the University of Washington, director of the Harborview Sleep Clinic, co-director of the University of Washington Medicine Sleep Center, and a past president of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, has quite a bit of knowledge in the realm of sleep health.

Watson explained that losing even 15 minutes of sleep on a regular basis can build up a sleep debt, and this cannot simply be paid off by sleeping in on the weekends. Alternatively, however, this debt can potentially be compensated for by making long-term adjustments.

“The good news is that if you start to extend your sleep time, go to bed when you’re tired, wake up spontaneously, and do that over a two or three week period, you should be able to get yourself back to normal,” Watson said. “So you can pay off a sleep debt, but it’s just not going to happen in one late sleep on Saturday or Sunday morning.”

In a study through the Institute of Medicine Committee on Sleep Medicine and Research, it was estimated that the number of people suffering from chronic sleep problems in the United States ranges from 50 to 70 million people. The study indicates that sleep loss and resultant sleep disorders come with several consequences for human health.

This often includes errors in judgment, increased mortality, decreased performance, accidents and injuries, functioning and quality of life, family well-being, use of health care, increased appetite, glucose intolerance, mental distress, depression, anxiety, and in some cases, alcoholism.

“Sleeping five hours or less increased mortality risk, from all causes, by roughly 15 percent,” according to the study. The optimal amount of sleep for adolescents ranges from 7 to 9 hours per night, and this needs to be met consistently, as catching up on sleep is not a solution.

“There’s no substitute for sleep. That’s the bottom line,” Watson said. “There’s nothing you could do or take that would be a complete substitute for sleep, so prioritizing sleep is a very simple, basically free thing that you can do to maximize your performance in all aspects of your life.”

According to Watson, people must respect the circadian rhythm of their bodies to maximize overall health.

“If you don’t respect the fact that your body has a circadian rhythm that dictates sleep and wake, and that all of our physiology is built to function awake during the day and asleep at night, you can walk down a pathway to an insomnia problem,” Watson said.

Watson explained that those who do prioritize sleep are significantly more likely to be the best version of themselves and perform to the best of their abilities during the day.

“We spend a third of our lives sleeping, so obviously it must be important,” Watson said. “Despite that fact, about a third of the U.S. population does not get the seven or more hours of sleep recommended on a nightly basis to support optimal health.”

Poor Sleep, Poor Academic Performance:

It’s easy to give up control over sleep patterns when one is attempting to balance so many different aspects of their life.

“It’s slipping into and not realizing how long you’re spending on certain activities,” Horton said. “If you continue to do that you’re likely to get sick, you’re likely to have trouble concentrating, not do as well academically, and you’re likely to have problems with relationships.”

In college, it can be difficult to balance all of one’s interests with the new freedom that comes with living without a parent or guardian. It requires students to learn a new sense of responsibility and accountability for their own actions, schedules, and time management skills.

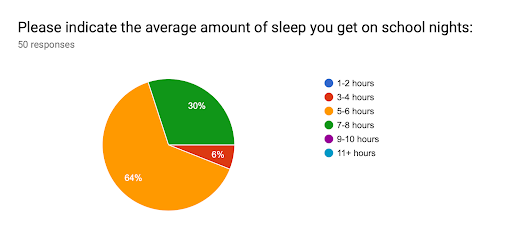

According to a poll of 50 Pepperdine students, 64% reported getting between five and six hours of sleep, 6% reported three to four, and only 30% meet the recommended seven to eight hours.

Some of the activities that most frequently cut into sleep included academics, homework, studying, and projects, social activities, time on social media, procrastination and time management. Balancing these areas appears to play a role in the lack of healthy sleep times listed above.

Additionally, 50% of students reported that their earliest classes start between 8 a.m. and 9 a.m. and 74% reported that their latest classes end between 6 p.m. and 10 p.m., indicating long days that can be especially draining, causing 56% of students to report drowsiness, 58% reporting fatigue, 54% reporting feeling distracted, and 62% feeling resultant anxiety and stress.

The first pie chart indicates the most frequent start times of students’ classes and the second figure is representative of when their latest classes typically end. Both indicate half beginning earlier than or at 9 a.m. and and more than half ending classes between 6 p.m. and 10 p.m.

This chart indicates the resultant symptoms that students undergo when participating in classes that range widely from early start times to late release. Common symptoms include drowsiness, fatigue, distraction, and anxiety or stress, however happiness was still selected by 50% of students in spite of their sleep deprivation.

It is clear that Pepperdine students are losing sleep. Instead of restructuring their habits, however, many fall into unhealthy patterns supplemented by artificial substances. The poll revealed that 74% of students turn to coffee or tea to reverse the effects of their sleep loss and 44% just deal with the issue and have adapted to their poor sleep patterns.

Neglecting the problem or using caffeine will not boost student success, in fact, such actions may limit it by promoting the continuation of poor sleep. The negative impacts of this habit can really creep up on students.

“The more sleep deprived we become, the worse we’re able to judge our level of impairment,” Watson said. “Unfortunately, a lot of times you’re not even going to be aware that you’re making mistakes when you’re sleep deprived.”

If students cannot even tell that they’re performing worse and making mistakes, they will not be able to change their habits and better their health.

“The quantity and quality of sleep affects our ability to learn and remember in two ways,” psychiatrist Dr. Alex Dimitriu said in the publication Sleep and Memory: How They Work Together. “First, adequate sleep enables us to concentrate so we can learn efficiently. Then, sleep itself is needed to consolidate memories of what has been learned.”

Memory and the ability to retain and conceptualize information are crucial processes for college students. When we learn new things, Dimitriu said, sleep is required for this information to be consolidated, stored in the brain, and recalled at later times. If students are not obtaining the recommended amount of sleep they will not retain as much information, therefore limiting what they take away from their classes, and ultimately reducing their academic success.

“You’re going to have memory lapses, you’re going to be more irritable, your mood will be affected, you may have a depressed mood, you may even find yourself falling asleep in the middle of lectures,” Watson said.

In addition to the implications of sleep loss on memory, Watson explained that students may experience microsleeps during class.

“You may have what are called microsleeps, which are little brief two or three second periods of sleep that occur during the day, and during which you’re not going to be absorbing the information that your teachers are trying to convey,” Watson said. “So what’s better, to stay up an additional two hours and study or sleep those two hours? I would suggest that sleeping is better for your academic performance.”

Even with the known damages to academic performance at the hands of sleep loss, students book study rooms late into the night and work instead of getting necessary rest.

Sleep Deprivation Affects Different Members of the Student Body:

When students are balancing so many important priorities, something is bound to get less attention in their schedules.

“Sleep often falls to the end of the list,” Jordan Holm, director of academics for the athletic department, said.

Like many, junior history major Callie Colvin often finds herself sacrificing sleep. Her situation took on an interesting layer of commitment as she studied abroad in Washington D.C., during the 2018-2019 school year. Students in D.C. actively participate in full day internships and jobs while taking night classes.

“I was so busy,” Colvin said. “Something had to dip. I would say sleep was sacrificed more than anything else.”

A typical day for Colvin began around 7:30 a.m. She would get to work at 9 a.m., and work until around 6 or 6:30 p.m., and arrive back home at 7 p.m. If she didn’t have night classes, she would do homework for the rest of the night, but on Tuesdays, with class from 7 p.m. to 11 p.m. she endured even later nights followed by homework.

“Going straight from work and straight to doing homework made my workday feel super long,” Colvin said. “I had to manage my time really well, because I didn’t have much of it. It was a lot of work, a lot of hours.”

With all that was going on, Colvin said she got a decent amount of sleep, amounting at six to seven hours per night. She observed that late night classes might not have been effective for all students.

“I was pretty dead by around 9 p.m., and from 10 to 11 you just wanted to get out of there so bad that it was harder to concentrate. I would caffeinate pretty strongly on those days,” Colvin said. “Sometimes it was hard to focus because my brain needed a break.”

Going into her internship at the Department of Justice after a bad night’s sleep strongly impacted Colvin.

“I felt super sleepy and I didn’t want to be there as much. This didn’t happen too often, but when it did it bothered me the whole day,” Colvin said.

She found that it affected her class performance a lot more.

“I had to be very strict with myself and with waking up on time,” Colvin said. “In class the only person that you’d be disappointing is yourself so it’s easier to slack. At work I had a lot more people dependent on me, so if I slacked off a lot of people would be affected.”

Finding a way to balance each aspect of her life was difficult for Colvin, as well as many students in her position.

“I couldn’t fulfill all of them; internship, class, and everything else. It would be one thing or the other, so I always chose my internship over class,” Colvin said. “I don’t think sleep was ever my priority which really showed. I should have valued sleep more, because I was so exhausted by the time I came home during Christmas.”

Colvin was only in D.C. for one semester and said she certainly felt the effects of such a busy lifestyle on her health.

“I felt kind of lethargic and like I was running on empty a little bit more, but I’m lucky that I never fell asleep at my internship or in class,” Colvin said with a smile.

Unfortunately, this was not the case for all students. Ally Richards, senior international studies major and non-profit and sports medicine minor, studied abroad in Heidelberg and shared a different experience.

“I fell asleep in Heidelberg during orientation and my professor woke me up by patting me on the head,” Richards said.

Everyone handles sleep loss differently and it is important to know one’s limits in order to be fully present throughout the day.

“It was hard to balance. If I were there the full year at that internship, there was no way I could sustain that lifestyle,” Colvin said. “I was able to justify it though, because I was doing stuff that I’d never done before and that I loved and felt was super important.”

While academics are extremely important, college students need to be able to socialize with their peers and focus of their health, as well.

“I had to be super good about planning my time, because I also really did want to work out and I did want to socialize,” Colvin said. “D.C. taught me that sometimes you do have to sacrifice parts so that you can continue to give your all.”

A study published by the American Psychological Association tested specifically for response time and cognitive changes that occur in decision making. During baseline and recovery periods, when the experimental and control groups matched in the amount of sleep they were allowed, responses were similar, however, during periods of sleep deprivation the experimental group demonstrated loss of accuracy as compared to the non-sleep deprived control group. The experimental group averaged response times that were over 200 milliseconds longer than the control group.

This data raises concern for student-athletes who need to be even more on top of their sleep habits to increase performance in their sport. Mackenzie Hamlett, first-year member of Pepperdine’s swim team, has a lot on her plate. Being a computer science and mathematics major requires a lot from a student and adding 20 hours of weekly practice and weekend meets into the mix can be a recipe for sleep deprivation. Hamlett practices and lifts weights three times a week, in the morning and afternoon, and takes two to three classes per day, making her busy from 6 a.m. until 7 p.m. After a long day bouncing between athletics and academics, Hamlett settles down to do homework.

“The study hall hours stop at 10 p.m., but I find myself in the library until 11:30 p.m. and then I’ll walk back to my room and study more,” Hamlett said. “I’ve studied up until 1 a.m. or 2 a.m. on some nights. Sometimes if there’s no choice, there’s no choice.”

Hamlett said she gets about five hours of sleep per night, significantly missing the mark for a healthy sleep schedule. Following late nights like these, Hamlett described that she feels slow to react at practice, doesn’t feel as awake, and finds it harder to think.

As a first-year student, Hamlett is figuring it all out and learning about time management.

“As a freshman I’m getting used to it. I know other people do activities, it just makes the workload hard,” Hamlett said.

Weekends are her saving grace. Having Sunday off allows her to do homework and study in the library. As far as sleeping on the weekends goes, Hamlett says she tries to catch up during this time and a lot of students share this mentality, however, as Watson explained, weekends just won’t do the trick.

Faculty and staff at Pepperdine said want to help students balance their busy schedules.

“It’s one of those things where there’s only so many hours in a day,” Holm said. “One of my biggest passions is to help empower student-athletes to explore other areas of interest they may have outside of their sport and the classroom, and to shed light on everything that Pepperdine has to offer.”

Holm works with student-athletes to help them navigate practices and class times so they do not conflict, meeting weekly with all of the first-year student-athletes and checking to see how classes are going and how they are transitioning.

Holm described the resources available to ensure that athletes are keeping up and keeping an eye on their health. First-years are required to spend four hours each week in a study hall. They can do so on their own time, but must be present in either a study area at Firestone Fieldhouse or at Payson Library. Help is available during study halls, and student-athletes also have access to academic counselors, tutors, and all campus resources.

“The best thing we can do as Administration, as coaches, is surround them with the knowledge and the resources to best themselves in all components of their life spiritually, physically, and academically, and sleep is a big part of that,” Holm said. “We have to remind them that all the things that they put above sleep are not going to be accomplished as well as they could be if sleep was prioritized.”

While there are plenty of resources, it seems that college athletes still aren’t getting enough sleep. This issue extends beyond Pepperdine.

In a study at the University of Arizona, 189 student-athletes were surveyed: 68% reported poor sleep quality, 87% reported getting less than or equal to eight hours, and 43% reported less than seven hours of sleep.

The study recommends that college athletes get between eight and nine hours of sleep to function at their best, but the vast majority shared that they are barely meeting this amount. Juggling athletics, academics, and employment can disturb sleep patterns, and for athletes, inadequate sleep not only impacts physical and mental state, but also performance in their sport by causing slower reaction times, impaired decision-making abilities, and depression or loss of interest.

Of the student-athletes surveyed at Pepperdine, 71% reported getting 5 to 6 hours of sleep each night, and the remaining 29% receive 7 to 8 hours. With academics and athletics being the most frequent interruptions to sleep among this group, the majority of the students are not getting a healthy amount of sleep, which is especially damaging to their focus and athletic performance.

Horton suggested that students reorder their priorities to get the best out of themselves. She recommends starting with the “non-negotiables,” like class, and putting sleep right after. She says students should set boundaries for themselves; times that they shouldn’t remain awake.

“After sleep and class are prioritized you can fill in time for other interests, friends, spiritual life,” Horton said. “If you have time to do all that great, but if you’re just feeling like you can’t fit it all in, just decide how much.”

If needed, making individual appointments at the Student Health Center is another option. Horton shared that the Health Center won’t just diagnose students and send them off with antibiotics or medications. Instead, they are there to have conversations about a student’s overall health. They will often ask about how much sleep a student is getting to find out if this frequent answer is the root of the problem.

“At Pepperdine we view people holistically. You’re not just a brain on a stick,” Horton said. “We don’t think of you like we’ve just got to feed you this information. We think you’re a person in a body that you have to be a good steward of, with a soul that needs to be formed in a healthy way and supported in that journey and with a body that needs to you know all those pieces.”

Anneliese Zeigenbein completed the reporting for this story in Jour 241 in Fall 2021 under the supervision of Dr.Elizabeth Smith. Dr. Littlefield supervised the web version of the story.