Good grades, enough sleep and a social life — pick two.

So goes the collegiate paradox. The internet-famous stress triangle doesn’t even account for students balancing employment too.

Students and experts at Pepperdine agreed that the benefits generally outweigh the costs of working while still a full-time student. Employed students gain time-management skills, experience in a professional setting and some spending money. On-campus jobs even more conveniently provide settings for students to gain independence.

“There’s an old saying that if you need something to get done, give it to a busy person,” Pepperdine Sociology Professor Bryant Crubaugh wrote in an email. “Work may provide structure and the need for time management that may actually allow students to get to their studies in a timely and efficient manner. Work can also give students the resources they need to not be hungry in class and to have the books they need to succeed.”

A Pepp Post poll of 52 students found that almost 77 percent of poll respondents said money was the primary reason they chose to work. However, many students working on campus said they’re able to take away more than a paycheck from their position.

Student employment at Pepperdine

Pepperdine employs more than 1400 undergraduate students, in addition to about 600 graduate students, said Jody Sturgeon, director of Student Employment at Pepperdine. Student workers comprise the largest employee class at the university, outnumbering faculty and staff.

Major on campus employers include the Athletics Department, Center for the Arts and Payson Library. Most jobs start at minimum wage, currently $13.25 in Malibu, although students in specialized roles often earn a higher rate, Sturgeon said. In 2018, student employees collectively earned a little over $5 million.

A majority of polled students work less than 15 hours per week — a healthy amount according to a 2015 study by Logan et al. using data from an Indiana University survey.

However, the poll found that 8 percent of students surveyed work 20 to 40 hours per week, while 2 percent said they work more than 40. Crubraugh said full-time students working more than 20 hours will start to feel the negative consequences in their academics and health.

Schedule struggles

Time becomes a precious and limited commodity when factoring in academic responsibilities with jobs, students said.

“Junior year was definitely the hardest year for me in terms of academics and working because I was a full-time student, and then all at the same time I was a full-time student, I was still a tour guide, I was a production intern and I was working at the marketing agency,” said Olivia Belda, a senior integrated marketing communication major. “So that was kind of like all at once, with also juggling all the exams I had and all of the work I had. And sometimes they’d ask me to take homework and I wouldn’t want to say no because I wanted to be the best employee I could be.”

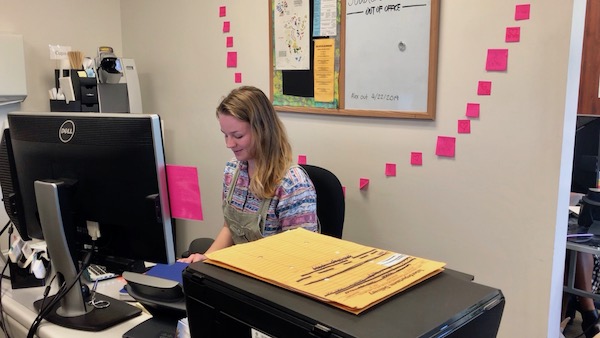

Gabi Meacham, a junior theatre and music major and the lead student worker of the Fine Arts Office, said her days are full without even accounting for study time.

“So I’m pretty much in school from like 9 to 10 a.m. to about 5 p.m. and then I always have about an hour before rehearsal starts,” Meacham said. “And then on top of that I also have to run my own rehearsals for my directing classes and whatnot.”

Senior psychology major Jordan Diab juggles a lot with school, her role in the International Programs Office and as a remote copywriter for an Arizona magazine.

“I keep telling myself that I’m never going to be busier than I am now,” Diab said. “ I don’t know if that’s true or not. Like I’m sure if I have the opportunity to be a mom — motherhood is pretty busy. And if I’m worried about my GPA now, imagine how worried I’m going to be when I have to keep a baby alive.”

Working overtime

Work for junior Jasmine Croom, a computer science and math double major, has become consuming. Not only does she entirely support herself, Croom sends about three-quarters of her paychecks back home to support her family.

“Last year was a blur,” Croom said. “Like I don’t even… it was absolutely terrible. I was overwhelmed and consistently exhausted. And I was pulling at least 40 hours here at Starbucks, and then my other jobs like 30 hours a week.”

Croom was managing a full load of classes on top of her four jobs, while participating in weekly Dance in Flight and Step Team rehearsals, leaving her only four or five hours per night to sleep.

“Growing up, I knew my family didn’t have a lot of money so I would do really drastic things,” Croom said. “I just wouldn’t ask for anything. I would never try and go out if it wasn’t covered for me. I would… I would not eat if it cut into… or if it required extra money, which was terrible considering I never slept and I had too much stuff to do all day.”

Aside from paying today’s bills, Croom sees working as an opportunity to pay back the money she felt guilty asking for as a kid.

Crubaugh is familiar with the tough financial situations that face students like Croom.

“I think that students who work more than 20 hours a week to send money to a family that needs it are going to have to have their priorities set and their time managed,” Crubaugh wrote. “I can imagine a student that can still engage in the community, but with the pressure from a job with serious consequences, it is less likely that students who need to work that much and need to do it for these reasons will be able to partake and still keep up academically.”

Employment can have a negative impact on a student’s academic achievement when they become more oriented toward work than classes, according to a 2017 study by Beart et al. published in Applied Economics Letters. Croom said she did watch her grades drop, especially last summer.

This year she’s down to two jobs but still works long hours. Money is tight but Croom recognizes how much she continues to overwork herself.

“I haven’t grown accustomed to it but I have gotten used to knowing that this is probably how it’s gonna be for a while,” Croom said.

A time management crash-course

Diligent time-management skills seem to emerge as the common coping mechanism for working students.

Diab said she’s more productive under an impending deadline without any time to mess around.

“I actually get more schoolwork done when I know I can only get homework done from like 8 to 2 a.m. for example,” Diab said. “Versus I have all day to get it done, I push it off. Procrastinate, procrastinate, procrastinate.”

Ben Hancock, a sophomore religion and philosophy major, has allocated his life into grids and cells.

“Going into the year knowing what I had to do — it involved Excel spreadsheets, really,” said Hancock, who serves as the Spiritual Life Advisor of Miller, co-president of Veritas Club and a member of the volleyball team. “It got to the point where it was like alright here’s my day, here’s where the minutes I’m going to be spending at these places.”

He said that while his grades may not be as high as possible if he had more time to study, his schedule helps avoid disarray.

Benefits beyond the paycheck

In addition to expert scheduling, student workers on campus think they’re gaining other life skills.

Diab cited the public speaking experience she’s gained in leading IP trainings, Hancock mentioned people skills and Meacham talked about working in an office setting.

“It’s very much an administrative place, so it’s really great to see that side of the arts as being someone who does the more creative performance side of things,” Meacham said. “ It’s really great to see what it takes to have everything running smoothly. It takes people who do spreadsheets and answer phones and come up with course catalogs.”

Amy Adams, the Pepperdine Career Center executive director, emphasizes such on-the-job growth in on-campus student roles.

“They’re learning through and earning money through, they are also building practical, professional skills that they need during that process,” Adams said. “If you’re a tour guide on campus, or you’re doing customer service or answering phones, or you’re processing data, you’re actually building skills that then make you marketable for an internship at a different level than if you just sort of got your homework done while you were getting paid to do the job.”

Entering the workforce

Regardless of the proclaimed benefits and opportunity for earnings, some students choose not to work, especially in their first year of college.

“I didn’t find anything that interested me that I could actually do,” freshman economics major Cindy Guo said. “Like if I was interested, I’m not qualified.”

Guo said she usually studies when not in class but wants to work on-campus her junior year after returning from abroad.

Anne Lopina, a sophomore business administration major, chose to seek work this year after not working as a freshman.

“I did think it would be a little bit stressful to have to worry about working and balancing that with classes, so I didn’t bother to look for a job last year,” Lopina said. “But this year since I knew what to expect with the course load of college and everything I felt like it’d be nice to have a little extra spending money and just, you know, an activity to do through working.”

Lopina babysits for an on-campus family and tutors several times per week for Humanities 111. She found the babysitting job on Pepperdine’s job portal Handshake and became a tutor by professor recommendation.

The poll found that a little over 30 percent of students surveyed found their current job on Handshake, and a majority had a friend or colleague refer them to a job.

Marisa Dragos completed the reporting for this story under the supervision of Dr. Christina Littlefield and Dr. Theresa de los Santos in Jour 241 in Spring 2019. Dr. Littlefield supervised the web story. Dr. de los Santos supervised the video package.