When Sergio Velazquez, a junior psychology major, sat down in the tattoo parlor he wasn’t thinking about how it would impact his career path or what people would think of when they saw him. He was thinking about his family.

A rising college sophomore at the time, Velazquez was getting ready to embark on his journey to Buenos Aires, where he would be away from his family for a year. He had spent the past three months creating a tattoo that would allow him to display his love for his brothers and bring his family with him.

Once the needle touched his skin, however, he did think, “This is going to hurt,” Velazquez said, but he doesn’t regret it.

A study in the International Journal of Innovative Research and Development found that “86% of young professionals did not think piercings and tattoos reduce the chance of getting jobs,” Annie Singer wrote in a Huff Post article. In comparison to the 38% of Millennials with tattoos, only 32% of Generation X, 15% of Boomers, and 6% of Silents reported having tattoos, Douglas L. Keene, Ph.D. and Rita Handrich, Ph.D. wrote in the article “Tattoos, Tolerance, Technology, and TMI: Welcome to the land of the Millenials.”

The stereotype of only gang members, bikers, thugs and alcoholics having tattoos seems to no longer be the norm. Tattoos are becoming more widely recognized as a form of self-expression that does not reflect one’s ability in the workplace.

“My mindset is if someone can’t respect my own personal choice or my personal body and it that offends them to the point where they can’t work with me, I don’t want to work with them,” Macy Scruggs, a junior advertising major, said about her tattoos and piercings.

Student Experience

In the 20 years Nancy Shatzer, industry specialist for the Seaver College Career Center, has worked at Pepperdine, her perception of body modifications on campus has changed.

“I have definitely seen a huge change in body art in our student body,” Shatzer said. “I think that it is much more expressive, and I think it is much more frequent.”

In a Pepp Post survey of 50 students in the Pepperdine community, 82% said they had a body modification. Of that percent, 46.8% believe their body modifications would be considered alternative. Scruggs is just one of those responses.

Believing in Change

For Scruggs, her tattoos and piercings are a form of self-expression. They’re something she’s always wanted, and despite her father’s persistent disapproval, she has more planned out. Currently, she has four tattoos (three of which are easily visible), and 10 piercings, including a nose piercing. Scruggs said she isn’t worried about having body modifications because she sees the younger generations as “more accepting and expressive” and wouldn’t want to work somewhere that can’t respect the decisions she’s made with her body. For Scruggs, tattoos have meaning, something she wants to carry on her body. She is not alone in this mentality.

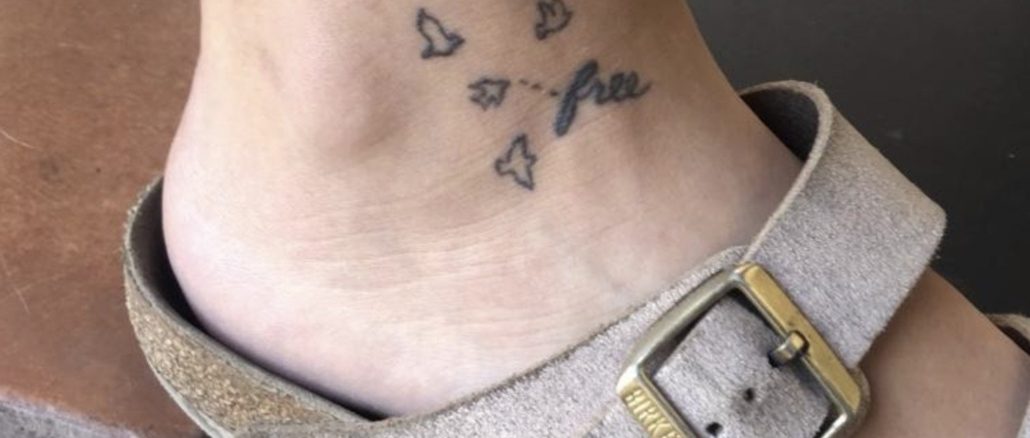

Macy Scruggs said her tattoos and piercings are a form of self-expression (Photos courtesty of Macy Scruggs).

“If anything, it should improve my character because I put things of meaning on my body,” said Emma Thomasson, a junior philosophy major, when asked how she thinks her body modifications will impact her career.

Thomasson has two tattoos, and both act as important reminders in her life. Her first tattoo on her wrist is to honor a friend’s death. Initially, she wore a bracelet with his name on it. Her other tattoo on her foot was to commemorate her baptism.

Having grown up in small-town Waco, Texas, she said she did think about her future when she got her first tattoo, and both she and her parents were worried she would be judged. After moving to California, she knows there are places that will hire her and accept her tattoos. When it came time to get her second tattoo, she didn’t even think about her future as a therapist.

Understanding Traditions

Like Thomasson, Velazquez also wants to be a therapist. Unlike Thomasson, Velazquez does think his tattoo will have some impact on his professional future, and he wouldn’t be surprised if he were asked to wear long sleeves in the workplace. Nevertheless, he doesn’t regret his tattoo either.

Velazquez and his two brothers created the design, and he sees it as a display of genuine love for his brothers that “openly shows the world a part of me,” he said.

His parents, especially his mother, were really against the idea of him and his brothers getting a tattoo, especially one on his forearm, which is not easy to hide. Velazquez isn’t alone in dealing with this disapproval, as 80% of students surveyed said a parent discouraged or prohibited them from getting a body modification.

The Concerns or Lack Of

The stigma of tattoos representing gang affiliations was one of the reasons his mother was so against the idea, but Velazquez said he believes that the stigma is changing. Tattoos are moving from criminal associations to personal expression, both meaningful and aesthetic.

Velazquez said he believes that the acceptance for a lot of things is growing, but there is a level of professionalism that should be kept. Body modifications are becoming more prevalent in the workplace and workers shouldn’t be judged for them, but there is a balance between self-expression and professionalism that’s being discovered. Velazquez is considering getting more tattoos but wants to wait.

“You might say you’d hire someone without tattoos over someone with them for a particular job. But when it comes right down to it, you’ll choose the most qualified person, body art or not,” said Micheal T. French, a professor in health management and policy at Mami Herbert Business School, in his interview with Harvard Business Review’s Alison Beard. “Even the U.S. Marines now allow recruits to have visible tattoos anywhere but the face because when tattoos were banned, the organization found it was losing out on good candidates.”

The definition of professionality, and what it means regarding body modifications in the workplace, is changing. Velazquez thinks that the stigma is still there, but the workplace has become more accepting. He saw faculty members at his Catholic high school with full sleeves and still thought they were professional.

Scruggs thinks there is “for sure” a difference between Baby Boomers’ and Millenial and Gen Z’s perception of body modifications. All 50 students surveyed believe that younger generations (Z and Millennials) are more accepting of body modifications than older generations.

Thomasson said she thinks that the change will happen no matter what and that the younger generations are already forcing a change in the workplace — even in those fields where more conservative baby boomers are the majority; the younger generations are the future workforce, and there is no future without them.

Only 8.7% of students are worried about their professional prospects due to their body modifications, according to the Pepp Post survey. While the stigma is changing and younger generations are seeing a place in the workplace for body modifications, 45.8% said they refrained from getting a body modification out of fear of how it could impact their professional future.

In the Workplace

It’s not only the students of Pepperdine that have alternative body modifications. Despite being seen as a more conservative campus, members of Pepperdine faculty have alternative body modifications and had them before coming to campus. Their experiences provide a real-life example of how body modifications are received in the workplace.

Collin Enriquez, visiting assistant professor of English, was in graduate school when he got his tragus and conch piercings. His piercings were meant to celebrate anniversaries and goals, and focused on this, he didn’t think about his professional future when he got them. It did cross his mind later on.

Enriquez already knew he wanted to go into academia, and though his piercing would make him a little edgy, they were worth the risk.

Growing up, piercings weren’t seen as professional, but he wanted to express himself — push the boundaries of his self-expression. He said he saw academia as “a gray area, and a bit non-traditional,” and although he did think his piercings could impact his job search later on, he wasn’t too concerned. During his job interviews, Enriquez noticed people looking at them, but the looks were more curious than judgmental.

“I think we probably hit the peak of its acceptance,” Enriquez said.

Younger generations are more accepting, but body modifications are still seen as different, even if they don’t limit your chances of employment.

Changing the Uniform

“[I have] a voice in the process of what professionalism can look like in my area and for the students I model,” said LaShunte Portrey, assistant director of recruitment and student development of International Programs.

Portrey has a forward helix piercing and a helix piercing, and while she grew up with the idea of professionally having a very traditional outfit, she believed the professional view of her piercing would be positive.

Having always lived in a big city — growing up in San Francisco, going to graduate school in New York City and now living in Los Angeles — Portrey has seen an evolution of consumers and the development of new notions of what it means to be professional.

That traditional professional outfit that Portrey thought of growing up did not include her natural hair, which Portrey considers a body modification alongside tattoos and piercings. She spent her life trying to change her hair, but after living in Tanzania, she developed ownership for her unique hair. She said that her self-expression shows students that they can express themselves in the workforce.

Despite Pepperdine’s more conservative image, Portrey said she wasn’t concerned but rather excited to come to Pepperdine with a sense of freedom in how she could express herself.

Her interest in marketing made Portrey think that her piercings wouldn’t impact her professional outlook because marketing “dresses the part of enthusiasm,” Portrey said.

Marketing focuses on images and perception, and there is a lot more freedom in her self-expression.

When she interviewed for her position, Portrey said she “had gone through enough life experience to know what she needed in order to thrive, and part of what [she] was asking for even as [she] interviewed was to be able to inhabit [her] space professionally… and needed to know that was OK and that [she] was stepping into a space that was welcoming.”

A study from the International Journal of Hospitality Management found that “grooming and business attire were more important indicators in the hiring decision than tattoos and piercings,” Singer wrote in her HuffPost article.

Despite this, however, another study by the University of St. Andrews found that “visible tattoos had a predominantly negative effect on employment selection, driven by the hiring manager’s perception of customer expectations,” Singer wrote.

The Communication of Body Mods

The recommendation of going conservative to be safe is prevalent and understandable, Sarah Ballard and Industry Specialists Nancy Shatzer and Yeneba Smith agreed.

Ballard teaches interpersonal communication, which focuses on the context of communication on a one-to-one scale and how to interpret non-verbal communication. Culture heavily influences how body modifications, such as tattoos and piercings, are interpreted. For example, in the United States, tattoos were once mainly associated with gangs or bad guys, but that has shifted to include creativity and self-expression.

The relationship between the communicators also influences the interpretation. Mutual friends can jump to conclusions about certain body modifications, or they can bond over them. In romantic relationships, tattoos can act as a public commitment that can even be open to interrogation.

The traditional view of tattoos in the workplace was a concern for how they would affect the image of the business. Ballard shared how her parents, who run a paint shop, didn’t want to hire anyone who had visible tattoos and didn’t want anyone they hired to get a tattoo because they feared it would make their business seem less than upstanding.

Between 70 and 90% of communication is non-verbal, and in Ballard’s opinion, body modification judgment is very subconscious due to earlier messages and media representation. While younger generations don’t see tattoos as a reflection of a person’s character in the same way, older generations see them as taboo. Ballard does think that individuals are more likely to get a job if they don’t have any visible tattoos when being interviewed.

Based on previous perceptions, tattoos can communicate that someone could be a negative person, more rebellious, more likely to get into trouble, etc. Ballard herself recently got a visible tattoo with her partner and said she was “quite anxious about getting a tattoo that was visible for fear it would cause judgment from students, or peers or supervisors” — especially at Pepperdine because the Christian faith sees tattoos as sacrilegious.

Looking to the Future

Shatzer’s industries are the arts, media, entertainment, communication and fine arts, which influences her opinion because she interacts with the widest variety of students out of all of the industry specialists.

Roughly 98% of students surveyed believe that certain industries, especially creative industries, are more open and accepting of body modifications among their employees. While Shatzer has never personally had feedback that students were unable to get a job because of body modifications, one can’t assume creative industries will always give a pass. Even in today’s society and in the arts industry, applicants with extensive tattoos and piercing may have trouble. It’s always safer to be more conservative when going into an interview in which the culture of a company is unknown.

Each company has different expectations for employees’ presentation. It all depends on the culture and environment; if an applicant has a good resumé and fits well despite tattoos and personal preference, they may be considered.

Smith, as the Industry Specialist for law, government, education and STEM, can’t see her industries changing to be open to large, visible body modifications. Between her industries, Smith sees government as the “strictest,” and body modifications would likely be frowned upon. The rest of her fields vary and depend on the company, and she counsels her students to go conservative if they don’t know. Once, before her time at Pepperdine, she worked with a student who had to buy makeup to cover her tattoos.

Smith chose to remain conservative with her decisions about body modifications, not because she was concerned about her future in education but because she didn’t want to. Smith did say she has considered getting one in commemoration of a lost loved one.

Melissa Locke completed the reporting for this story under the supervision of Dr. Elizabeth Smith and Dr. Theresa de los Santos in Jour 241 in Fall 2019. Dr. Smith supervised the web story.