*The subjects of this story asked that their names be changed because of immigration status.

Growing up Caitlin* had a typical, middle class, “picket-fence” life.

She grew up in a Maryland suburb with a brother, sister and labrador retriever. Her father was an engineer and her mom stayed at home to raise her family.

“In high school I got good grades, played varsity sports, did extracurricular activities and worked part-time,” Caitlin wrote in an email.

Back then, if someone asked Caitlin about her thoughts on immigration, she wouldn’t have had much to say. She would only be able to point at her Guatemalan housekeeper.

“I thought of her as someone from a different world,” Caitlin wrote. “I never related to her as a mom who had kids just like my mom did, or a husband who was like my dad.”

Like many people involved in the immigration debate, Caitlin said she thought of immigrants as an “other.” To her, her housekeeper was defined by her occupation. She didn’t think about how her housekeeper spent her holidays or who she spent them with, only her duties cleaning.

Her mindset didn’t change in college.

“In college there were Peruvian construction workers in the Home Depot parking lot, but I never thought of them as fathers or brothers or that they’d risked their lives to stand in that parking lot and beg for work,” Caitlin wrote.

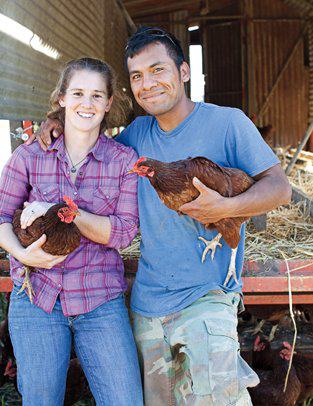

Fast-forward 12 years and Caitlin, now 33, runs an organic chicken farm in Santa Cruz, California with Angel*, an undocumented Mexican immigrant.

And he’s not just the help. He’s her husband. And the father to their 2-year-old son.

“I started farming by accident, after being vegetarian on and off due to dislike of industrial meat production. I didn’t know there was an alternative, so I decided to raise my own (chickens, to eat),” Caitlin said.

At the time, Caitlin’s farm was in a league of its own. Most of the other farms in her area were specializing in diversified vegetables.

“There wasn’t much competition,” Angel said.

She met Angel in 2009 after being set-up together by a friend. That same year they opened up their chicken farm together near Santa Cruz.

“I knew the production side of farming,” Angel wrote. “I always dreamed of doing something for myself, on my own, and at my job on the vegetable farm I was in a position of already having learned a lot about farming but not being able to do everything I was capable of.”

Together they made the perfect combination.

The farm provides organic poultry, eggs, pigs and turkey.

Once they were together, Caitlin said she could no longer see the immigrant as “the other.” Their cultures and histories were now one. The immigrant story became her story.

This was symbolized at their wedding.

“We had about 100 guests,” Caitlin wrote. “It was outdoors overlooking the ocean and a strawberry field. We had an English and Spanish ceremony. Just about all of my family, and the members of Angel’s family that are currently in the U.S. came.”

This wedding didn’t lead to citizenship for her husband.

“Marrying a U.S. citizen does not get someone automatic citizenship,” Caitlin wrote. “Neither does having a child with them.”

They are still trying to attain U.S. citizenship for Angel.

“We have probably made our immigration process harder by starting the farm,” Angel wrote. “Our finances don’t conform to what immigration officials are looking for, since a lot of my ‘income’ in the start-up phase is equity or assets rather than a regular paycheck.”

Caitlin and Angel have to be more careful than most couples because a wrong move could mean they have to move to Mexico.

A wrong move could also mean shutting down their farm.

With this new life comes harder decisions. And since the couple has a son these decisions are even more impactful.

“We will always decide in favor of keeping our family unit together, so if that means packing up and moving to Mexico, we’re prepared to do that,” Caitlin wrote. “Ideally we hope to gain the freedom to travel back and forth freely, so that we can raise him in both cultures.”

This upbringing is completely different than the one her parents were able to provide for her.

“Our quality of life is so much lower than it would be if we just had normal jobs,” Caitlin said.

One motivation that keeps them working the farm is that Caitlin and Angel are able to provide better working conditions for the documented immigrants they employ.

“Smaller farms (regardless of organic status) can offer workers more diverse work, which I think cuts down on repetitive motion injuries,” Caitlin wrote.

This is the benefit of working on a smaller farm, even if the wages aren’t as high.

“In many cases these farms were started by people who specifically wanted to take on and ameliorate ethical issues in the farming industry, including quality of life for workers,” Caitlin wrote.

Once Caitlin became a farm owner she said her views on regulations changed.

“Farmworkers deserve to work in a responsibly-managed work environment,” Caitlin wrote. “But I also know of some well-meaning ‘protections’ that they don’t appreciate, like regulations around over-time.”

Her experiences allow her to look at immigration issues from both sides — that of the immigrant and that of the U.S. citizen.

She is even critical of President Barack Obama’s executive order on immigration.

“I feel like Congress, on both sides of the aisle, is failing to govern on this issue, so I did nod in agreement when Obama said in his speech, ‘If you don’t like it, then pass a bill,’ ” Caitlin wrote. “But I question the constitutionality of the executive action. I think it is important that our government officials respect the separation of powers laid out in the Constitution. … That’s what makes this country a great place that people want to immigrate to.”

However, there is one point Caitlin doesn’t sway on: her belief that all immigrants should be treated foremost as human beings, and then “as a valued labor force that cheerfully do the jobs that U.S. citizens would rather collect social entitlement payments than do themselves.”

Caitlin chose the life she is living. At any given point she is able to opt-out of it and work in an industry that utilized her educational background.. After all, she does have a Bachelor’s and a Master’s degree, though she didn’t say from where or in what.

But many immigrants don’t have a way out of their given situation, Caitlin said. It is a means of survival.

“If you can afford to eat out, or live in a house that you paid someone else to build for you, then you can probably thank the immigrant labor force,” Caitlin said.