The man should not have gotten surgery.

He shouldn’t have even been seen by a physician.

His heart had always had an irregular beat, but it had been getting worse.

More unpredictable, weaker.

It was by chance that he met a doctor just starting his residency in the United States, a doctor who had practiced in Egypt, Libya and Dubai, where the concept of needing health insurance to receive care was foreign.

They didn’t meet in a hospital.

The man in need – a Hispanic immigrant, likely undocumented – was afraid to go there. They met in a church in Hollywood that moonlighted as a clinic on the weekends.

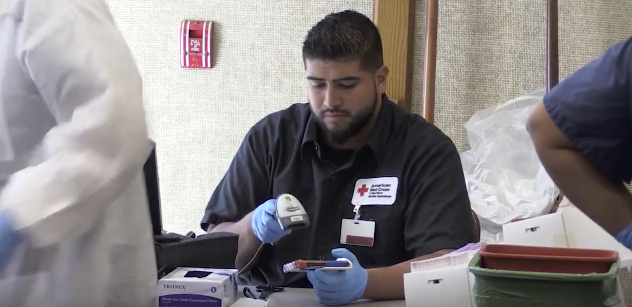

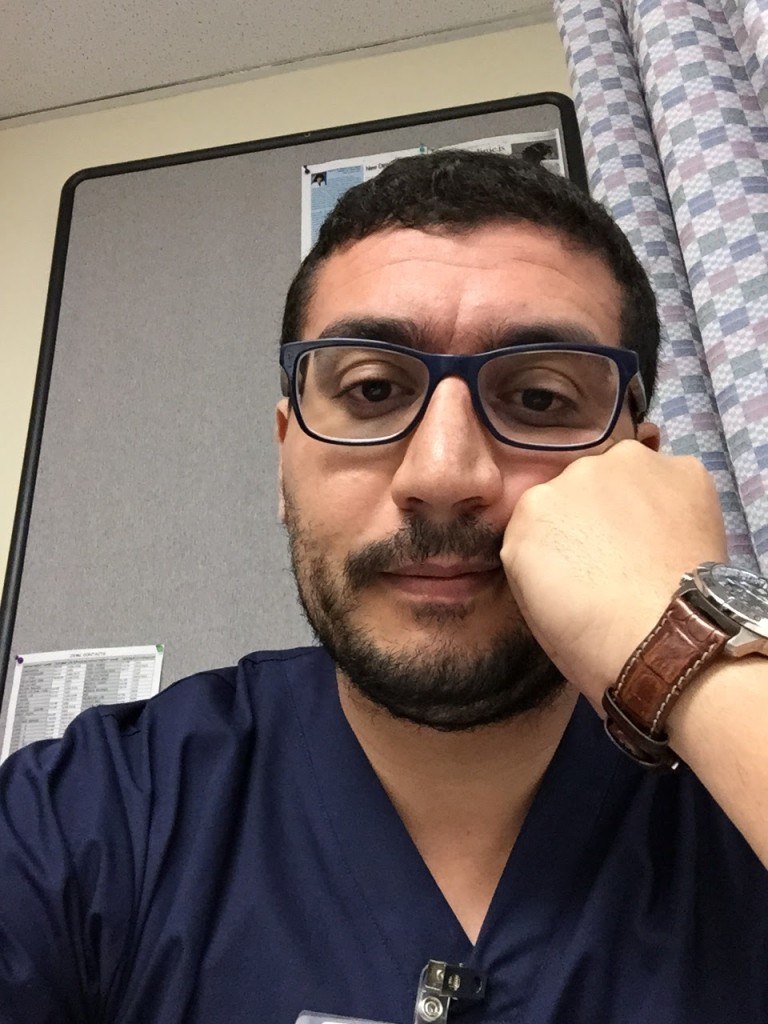

Dr. Jalal Dufani, a second-year resident, was on his first week of rounds at Olive View Hospital in Sylmar, California. Dufani said he does his job because he is able to helps others, and in return, others unknowingly inspire him.

“I didn’t know the system here and I gave him my number,” Dufani said. “He had an arrhythmia.”

The man called him two weeks later, saying his symptoms had gotten worse.

Go to the hospital, Dufani said. I’ll meet you there.

Dufani made a call.

***

Dufani grew up inundated with government hospitals, patient calls, waiting rooms and medical jargon. Both of his parents practice medicine, first in Dubai and then Tripoli, Libya. His mother Dr. Souad Jarallah is an opthamologist; his father Dr. Mohamed Dufani is a professor of pediatric neurosurgery at the University of Tripoli Medical School.

Dufani, now 28, described the hustle of the hospital as “the sound he and his brother and sister grew up hearing.” His sister Manal, 33, is a pediatrician, his brother, Mohanned, 22, is in his fourth year of medical school. Amongst a family of physicians, it seemed a given that Dufani would become a doctor. But after he graduated high school, Dufani wasn’t sure what he wanted to do.

An avid polo player and self-proclaimed rebel in high school, Dufani said many of his teachers would be shocked that he is now a doctor. He was caught smoking cigarettes in the bathroom of his school countless times and often skipped class to watch polo matches. His absences were almost guaranteed if Argentina or Eduardo Novillo Astrada were playing.

After graduating high school, Dufani didn’t have much direction.

A phone call from his father was the catalyst that jumpstarted Dufani’s career path. He was 17 and playing FIFA when he received the call from his father.

It wasn’t a question of whether or not Dufani wanted to attend medical school, but where he would go.

“Do medicine or do nothing, that’s the house I grew up in.”

Becoming a doctor was never Dufani’s childhood dream; a professional polo player perhaps, but not a physician. With an acceptance guaranteed because of his father’s name, he started medical school.

The challenge of the classes kept Dufani’s attention, but he still wasn’t sure that health science was his dream career. He kept at it because he said he felt it was expected of him.

It was after his first two years at the University of Tripoli when Dufani “first felt like a doctor.” He spent his third year of medical school in Dubai, feeling unchallenged, and took a year off to work for the World Health Organization (WHO) in Italy. During this time, Dufani packaged vaccines being sent to needy countries, like Africa and South America.

After working with WHO, Dufani decided he wanted to learn more about low-income and poverty-stricken areas at the University of Cairo in Egypt. It was a harsh, pixelated contrast to the wealth he had seen in both Dubai and Tripoli. In Dubai, Dufani explained, there are no homeless people. The government pays for their shelter and food if they have no family to help provide for them.

Egypt was his first introduction to the concept of needing “health insurance” to receive treatment. In Libya and Dubai, the government pays for healthcare too.

It wasn’t WHO or his time in Cairo that finally propelled Dufani into developing a passion for the field of healthcare, but Chad, Africa. In 2008, he travelled to Chad with the Libyan Red Crescent, an organization similar to the Red Cross, to provide vaccinations to Africans.

It didn’t feel real to him at first, seeing people like this. He recalls women and children being overjoyed at the sight of a loaf of bread, tears running down the curves of their cheekbones as they thanked him and thanked him.

That was the moment. That was the moment he knew he wanted to practice medicine as a lifelong career.

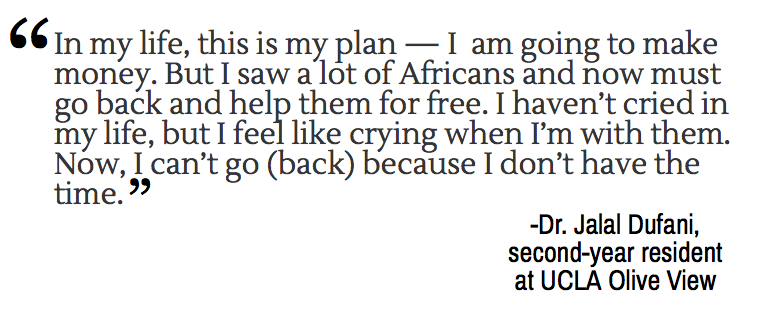

“The only thing that makes me want to be a doctor is these (African) people,” Dufani said, his voice suddenly deeper and his words wistful.

Initially, being a doctor meant only wealth and stability to Dufani. But after visiting Chad, his motivation changed. His life was no longer focused on FIFA or staying out all night partying with friends — he dedicated himself to a career filled with purpose.

“… I don’t care about the money,” Dufani said.

“In my life, this is my plan — I am going to make money. But I saw a lot of Africans and now must go back and help them for free. I haven’t cried in my life, but I feel like crying when I’m with them. Now, I can’t go (back) because I don’t have the time.”

With a clear end goal in mind, Dufani graduated from the University of Cairo and moved back to Libya in 2011. A few months later, the Libyan Revolt started. In a time when his country was in total disarray, Dufani returned to work in Tripoli Central Hospital. His family was also unable to leave Libya during the revolution because Dufani’s father did not agree with the then-leader, Muammar Gaddafi.

Dufani treated many victims of the revolution and after a long year, decided that he wanted to sharpen his training and challenge himself by continuing his education in the United States.

The United States Medical Licensing Exam was the hardest of his life, Dufani said. The pressure was high. He knew that in order to impress U.S. medical schools, he would have to do exceptionally well on this nine-hour exam.

After receiving a score of 255 out of 270, all Dufani had left to do was apply to schools. The Libyan government pays for its citizens to receive up to 14 years of outside education plus health insurance. This money is given with the expectation that the citizens will return to Libya, but Dufani said he has no intention of returning.

He accepted the funding anyway.

It took Dufani seven months to procure a student visa to study in the United States. He worried over whether or not he would be accepted at any schools since accepting an international student requires more paperwork — but later received his acceptance to UCLA’s cardiology residency program in 2013.

Life after his acceptance looked a little different for Dufani: his outlook on life became more serious and he put aside all his childhood frivolity.

“I have more responsibility now,” Dufani said, looking at his board exam prep book on the table. “I don’t go out … I don’t really have time. Now I just study. And I study now to learn, not just to pass.”

Dufani asked that his residency position be relocated to UCLA Olive View in Sylmar, California, one of the poorest areas in the San Fernando Valley. He now volunteers with the Center for Disease Control in facilitating Chagas research with immigrants from South and Central America.

Chagas is a debilitating parasitic disease that initially shows up as extreme loss of appetite and weight. After many years of remaining undiagnosed, Chagas can cause congestive heart failure and due to an enlarged colon, severe digestive problems.

Dufani sees a wide range of patients during the week. But when he volunteers during the weekend he sees roughly 200 to 300 patients to test for Chagas.

After practicing in so many countries, Dufani can get his healthcare systems confused, but his primary concern is the patient. He is passionate about the immigrant, the uninsured and those with low-incomes. He said he tries to treat his patients more like friends than doctor and patient.

“The thing that makes me happy to be a doctor is that I can help these poor people.”

***

Dufani, when encountering a man who needed immediate cardiac surgery, called a colleague and helped him jump the line. That’s the way things were done where he is from: People need care, they get care.

The surgeon performed the ventricular fibrillation pro bono, likely saving the man’s life.

But Dufani said he came out of surgery with a warning from other surgeons: Don’t do that again.

Dufani doesn’t intend to bypass the chain of command in a hospital again — but he is determined to find other avenues to help people get treatment, no matter what.

“Every month he called and thanked me,” Dufani said. “It was surgery by luck. It was my first week in the hospital. All patients know that cardiac surgery costs a lot.”

With a warm and quirky smile, Dufani said that every so often, home-cooked tamales are left at the hospital under his name, and that he occasionally receives a call from one of his first patients.

“Dr. Jalal, thank you for giving me more life.”