It was three days before Ayame Ino Kristofferson’s 12th birthday when social workers removed her from her father’s home in California because of his hoarding problem and placed her in foster care.

For the next six years, she bounced around between a variety of foster homes, emergency shelters and residential treatment centers.

“I lost count of how many homes I was in,” she said.

Kristofferson lived in every city in Ventura County, except for Simi Valley. During care, Kristofferson, now 21, said she didn’t have a single person she felt she could rely on.

“That’s especially because as you go through different homes and stuff like that, you make connections and then you lose them,” she said.

Kristofferson is not alone in this experience, as California serves more foster youth than any other state — 56,771 children out of 415,129 nationally, according to September 2014 data from the Administration for Children and Families.

Approximately 22,000 youth were emancipated in the 2014 fiscal year, meaning they reached their state’s legal age, left foster care and were on their own, according to the 2014 Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System Report.

As youth transition out of the foster care system, they are faced with numerous challenges, such as homelessness, mental health complications often resulting from trauma, as well as educational and occupational struggles. Although recent legislation has increased the government’s safety net for foster youth and nonprofits fight to eradicate these problems, there is always more work to be done.

“Imagine if you were 18 years of age and you’re kicked out of the house,” said John DeGarmo, a foster parent and author of several foster care books who has a doctorate in educational leadership. “And your parents say, ‘Hey, don’t ever call us again, don’t ever contact us again, if you have a flat tire we’re not going to help you, don’t come home for Christmas, we’re not going to sing you happy birthday, you’re on your own, find a place to live, good luck finding a job.”

Of the youth in foster care in California, Ventura County cares for 961 youth and Los Angeles County cares for 20,651, according to Kidsdata. Numerous attempts to interview officials with the Los Angeles County Department of Child and Family Services for this story were unsuccessful.

Peggy Stewart, a licensed clinical social worker at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, sees foster care youth struggle as they age out of the system.

“Foster care youth are a vulnerable population that really fly under the radar,” Stewart said. “Adolescents who are transitioning were in a structured living environment previously, have aged out and are homeless. A lot of these kids spiral, their future is bleak, so they turn to drugs, they turn to gangs, because what else do they have? They don’t have a strong foundation to begin with. They are just left to navigate adulthood on their own without any real resources.”

She works on them one-on-one as they come in for help.

“I am really on the front line — working directly — doing patient care with the foster care youth,” Stewart said. “Perhaps they have come in because of a suicide attempt or homelessness. They are looking for help, they are confused, frustrated, and do not know what to do. Wanting to help them is what drove me to work with foster youth.”

The challenges: Homelessness

Foster youth who outgrow the foster care system by aging out are called youth in transition, and they experience more cases of homelessness and financial instability than the majority population, according to a 2011 report by the National Youth in Transition Database. The Department of Health and Human Services created the database in 2010, and has collects data on foster youth, according to the Children’s Bureau website.

Most of the youth in the National Youth Database’s survey, 98,561 of them, received independent living services. But the 17,021 other youth surveyed reported they did not receive these types of services. The study showed that 16 percent of the 17-year-old foster care youth reported being homeless in their lifetimes.

In California, a fifth of all the youth interviewed reported having been homeless for at least a night or more, according to the California Youth Transitions to Adulthood Study. Out of 134 respondents who were out of care, approximately 4 percent reported homelessness as their current living situation.

“Homelessness is the original presenting problem,” Stewart said. “When you look at it, that’s where it all starts and that’s where it all ends — it’s a cycle. Once they leave their so-called stable living environment in foster care, they are faced with the big question mark of ‘Where am I going to live?’ They become depressed and self-medicate. How are you going to think about education if you don’t have anywhere to live?”

Stewart said there needs to be a change in the way transitioning youth are treated.

“I think this population does warrant a nod or some kind of special attention, and I don’t know what specifically that would be, but some kind of carve out of DCFS or a social work management where each foster care youth would be assigned a social worker for the first couple of years of transition to adulthood so they could become productive members of society,” Stewart said. “It all sounds a little utopian, but money spent on the front end could save money spent on the back end.”

Mental health

Foster youth who age out of care also experience mental health issues, as one-third of youth experienced mental health concerns such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, social phobia, alcoholism or substance abuse in a Chapin Hall study. This long-term study on foster youth in the Midwest provides a comprehensive evaluation of their transition to adulthood. Researchers interviewed more than 700 foster youth who were in care and out of care to compare these populations in terms of education, places of residence, mental health and overall well being.

These findings were consistent with the California Youth Transitions to Adulthood study, which showed that approximately one in five youth screened positive for at least one mental health disorder and approximately one in seven screened positive for alcohol or substance abuse.

Amongst major societal setbacks such as a lack of a high school diploma, many of these youth suffer from trauma, learning disabilities and drug exposure in-utero, Melina Meshad, supervisor for Youth Services in Ventura County, said.

“Trauma affects the brain, trauma affects learning, if you’re always on guard you’re not curious, you fall way behind when you’ve grown up in a serious trauma environment,” she said.

Meshad has been in the field for eight years, starting as a social worker mainly focusing on unifying families. She then went on to work directly with foster youth and now serves as a supervisor for Ventura County.

Therapist Dianne Nicholas is an outside contractor who works with foster youth in Ventura County. Focusing largely on trauma and its effects on the brain, Nicholas works to help youth make sense of their experiences, and develop appropriate programs to assist them with their difficulties, she said. Every youth she interacts with is an individual with so many factors that make up who they are, and there is not one easy fix for any problem, she said.

“For me it’s like peeling an onion,” Nicholas said. “What you see on the surface is very much not what’s really underneath, but by the time they get up to that age it’s because they’ve sort of created this very hard outer shell that protects them.”

One of the most common challenges Nicholas said she sees is a general lack of trust and connection, especially with the older youth. One of the goals in therapy is to provide a space where these youth can feel safe to share their trauma history and process it with them, she said. Oftentimes, trauma that occurs when children are young is internalized and many begin to think there is something wrong with them or that the experience was their fault.

“It can be a very profound, changing moment for kids when they really connect with a therapist,” Nicholas said.

One of the largest misconceptions of foster children is that they will stay the same, Nicholas said.

“That they will never change, that they are bad kids,” she said. “We have so much research done now that we know that the brain is plastic and it can change with new experiences.”

The assumption that these traumatic experiences can be quickly reversed by giving a child a nice home is a misconception, as it takes time, she said.

“It takes a multitude of interventions and interactions to get those hardwired belief systems to sort of break down,” she said. “So this is a long process and sometimes they may never 100 percent trust people, but what we hope for is to get a shift at least.”

Although the brain can be synaptically changed with new experiences, many youth unfortunately also have structural changes as a result of alcohol or drug exposure in-utero, she said.

Kristofferson also said how even with therapy, aspects of her individual challenges still follow her in her everyday life.

“Even if you thought you’d gotten over it, you already talked about it with a therapist or something like that or you let it go, the fact is that it never really goes away,” she said.

Also plaguing the system is a general lack of foster parents available in California.

“People don’t want to deal with this, a lot of people who want to take in foster kids say, ‘Do you have a cute little white 2-year-old?’” Meshad said.

Because the culture of the United States is independent in nature, Meshad said that people are typically less willing to help out in this way unless it is a very close-knit community.

“It’s almost impossible to find foster homes for older kids and really almost impossible to do teens,” Meshad said.

Many of these youth will go to group homes, emergency shelters or treatment centers. Foster parents get burnt out quickly with the older youth as they tend to have serious attachment problems amongst other issues, and parents will usually not form a wonderful relationship with their foster youth, Meshad said.

Emotional trauma

DeGarmo said he has seen the statistics of mental health and emotional concerns play out.

“I see it all the time,” DeGarmo said. “I have lived it as I have had children in my own home who have transitioned out. Some have succeeded and some have not. The realities are very real, and much of society has no clue.”

DeGarmo said he has had more than 50 foster care children in his home over the course of 14 years spanning from as young as 27 hours old to 18 years old. He said he has three biological children and has adopted three from foster care.

“Some kids stay until 18 years of age, and some until 21, depending on the state,” DeGarmo said. “Generally when the child leaves the system, the system is no longer able to provide for the child because of the child’s age. The cycle often repeats itself. For instance, two of the three that I have adopted are third-generation foster care.”

He said the average foster child does not have the social skills or resources to survive.

He said the problem facing foster youth transitioning out of care is that many of them have never had a stable environment, or a place where they learned the skills necessary to function as adults. When they age out, they have no place to go and don’t know where to start.

“When they do go through multiple displacements, each multiple displacement creates another attachment trauma,” DeGarmo said. “The more times they move, the more times they are going to have issues of trust, they are going to be emotionally unstable, and have issues of anxiety. They won’t know how to hold down a job, or how to apply for a job. How do they learn how to cook a meal? To open up a bank account? To get a driver’s license? How can they learn these skills if they are bouncing from home to home to home?”

DeGarmo said youth in transition simply need support from foster parents, caseworkers or someone else in their life. The best way to help foster youth succeed is through offering them continual support even after they leave care, DeGarmo said.

Employment

The Midwest Chapin Hall study included looking at employment and economic insecurity as well. Researchers found that 40 percent of the transitioning youth were employed and 90 percent of them earned less than $10,000 a year.

These findings were also consistent in California Youth Transitions study showed that of all the respondents with a bank account, most reported a balance between $1 and $1,000. In addition, approximately one third of youth reported borrowing food or food money from friends and one in six reported skipping meals because they couldn’t afford to buy them.

Youth in transition experience more cases of financial instability than the majority population, according to the 2011 National Youth Database report. The report shows that 28 percent of the youth had at least one prior employment experience, and 18 percent of the youth had received some form of financial assistance. Two years later, the database surveyed the same youths, and 34 percent of the youth were employed and 44 percent were receiving some form of financial assistance.

Although Kristofferson left formal foster care at age 18, she enrolled in college at San Francisco State and did not officially leave the system until she was 20. Now, she works at a retail store and pays for her expenses with little to no additional funding.

“I do everything on my own now,” she said.

One of the complications she has seen in her job after having been in foster care, is how easily she can be triggered emotionally by things that happened in the past.

“For example, a mildly annoying customer could easily trigger something from the past that would cause you to react more severely than it should have,” she said. “And you can’t help it because it’s unconscious whether you want it or not.”

Education

Youth in foster care generally have lower education levels than the national sample of same-age youth, as 87 percent of the 17 year olds surveyed in the 2011 National Youth database had not received any form of educational certificate.

Foster youth are more likely than other students to drop out of school and are less likely to complete a bachelor’s degree or any higher education degree. Only 1.8 percent of foster youth completed a bachelor’s degree before 25 years old, according to the Casey Family Programs’ 2003 Northwest Foster Care Alumni Study.

DeGarmo said having access to an education can open doors for transitioning youth.

“We had a child come to us when she was 17-years-old with three adoptions,” he said. “All three adoptions failed because they all abused her whether sexually, physically or emotionally. She had tremendous issues of trust. Now she is 25, she works for child welfare, she had a baby and I am the ‘grandpa.’ We never gave up on her and we got her in college.”

There were approximately 7,427 foster youth in the Los Angeles Unified School District in the 2015-2016 school year, according to LAUSD’s official website. Educational achievement among foster youth is typically less than the normal population, as one-third of foster children move schools due to multiple placements, according to LAUSD’s Foster Youth Achievement executive summary.

La Shona Jenkins, the coordinator of LAUSD’s Foster Youth Achievement Program, said she has seen the struggles of youth first-hand, especially when foster youth were being kicked out of the system before 21, prior to the option of extended foster care.

“We don’t really see it so much now, because they aren’t emancipating them at 18, but before AB-12 they were still in high school and would end up not having a place to stay,” Jenkins said. “We are not seeing it as much, because by the time they graduate high school, they are still in the system.”

California’s AB-12, the California Fostering Connections to Success Act, created the option to extend foster care from 18 years old to 21 years old for youth who were eligible, and took effect in 2012, according to a fact sheet about the bill.

Many foster youth have their education disrupted as they are moved from home to home. The resulting stress leads to lower educational performance than their peers, as their test scores, grades and credits are affected. It is difficult for many foster students to learn at the same pace as their peers, as 25 percent of the foster students have a limited English vocabulary.

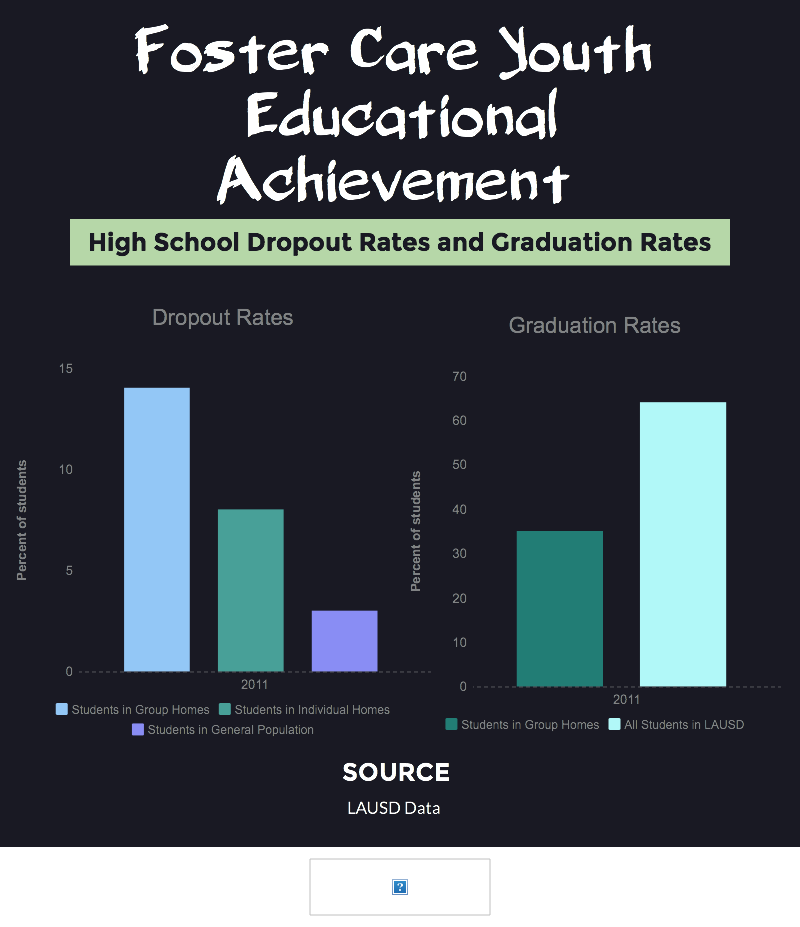

Research from 2009 to 2010 indicated that 10 percent of foster care students in the Los Angeles school district were placed in group homes, a total of 834 students. Group homes vary in size, because they can be smaller home settings or larger institutions. They also vary in their treatment programs and the number of children in the home, according to the California Department of Social Services. All group homes provide 24/7 care to children living in the home.

The students who had their homes changed more than three times struggled more in school in terms of falling behind in grade level and missing class time, according to LAUSD’s Group Home Scholars Program executive summary. Some 14 percent of students in group homes in LAUSD were likely to drop out, which is higher than the 8 percent dropout rate for foster care students who were in individual family homes. The same year, just shy of 25 percent of students in the general population dropped out of school, according to a 2011 report from LAUSD.

In addition, students in group homes had a 35 percent graduation rate, which is lower than other students in care, according to the report. The graduation rate for all students in LAUSD is just over 64 percent.

The solutions: Legislation for housing and training

United States lawmakers have passed federal and statewide legislation to increase funding and improve the status of foster care youth who are aging out of the system, according to a National Governor’s Association 2007 report.

The Foster Care Independence Act, which Congress passed in 1999, applied to youth between 18 and 21 years old. It gave federal funding to states as a contribution to their programs to increase the opportunities in education, employment, healthcare, housing, counseling and the instruction of basic life skills for foster youth transitioning out of care, according to the Social Security Administration. It authorized independent living programs, which mainly work to increase self-sufficiency of youth in transition, and allow each county to create their own services, according to the Department of Social Services website.

The Foster Care Independence Act created the John H. Chafee Foster Care Independence Program, giving states greater independence in determining which issues for foster care youth had the highest priority.

The Chafee Foster Care Independence Program funds help for education, employment, financial management, housing and emotional support, according to a program description from the Administration for Children and Families.

Multiple attempts to interview federal officials with Administration for Children and Families were unsuccessful.

The Chafee program also created an Educational and Training Voucher Program, which funds the cost of a higher education institution and gives youth who qualify $5,000, according to a report from the National Foster Care Coalition. Youth are eligible for the vouchers after they turn 18 years old, and can participate in the program until they turn 21.

California Sen. Jim Beall and Rep. Karen Bass co-authored Assembly Bill 12 (AB-12), which lawmakers signed it into law Sept. 30, 2010. It took effect Jan. 1, 2012, extending foster care services to 21-year-old youth who qualify, according to the bill.

Requirements to apply for the foster care extension include being enrolled in a high school or equivalent educational program, being enrolled in college or some vocational education program, being employed 80 hours a month or more, or working toward getting employment, with the exception being a medical condition, according to the fact sheet.

AB-12 is a fundamental change for foster youth as they used to be sent away at age 18 with little to no direction, Meshad said. With the new law, youth can have case managers still helping them and can benefit from various county measures. For instance, Ventura County will help provide youth with college books amongst other things, Meshad said.

Stewart said that although the legislation has been helpful, the application process still presents problems.

“Even as a student, it can be a cumbersome process to apply for any type of funding,” Stewart said. “How many of these kids have the skills to start applying for grants? They need that help or assistance. They need partnership to help them ease into adulthood and assist them and mentor them through the process of applying for scholarships and helping them get housing — that’s why we have a proliferation of this population on the streets in Hollywood.”

Although it should be the responsibility of the foster parent to make sure that transitioning youth apply for these programs, the circumstances of the foster parents might make this impossible, Stewart said.

“Yes, arguably it is the responsibility of the foster parent, but you have to analyze how capable the last foster parents are to do this,” Stewart said. “I think it is naive to assume that there are all of these situations where the foster parents can somehow guide and direct and provide hands-on assistance to the kids to access programs or scholarships for higher education or grants.”

DeGarmo said the recent legislation provides steps toward bettering the outcome, but transitioning youth still need help accessing these resources.

“It improves the situation for children whether they are 18 or 21,” DeGarmo said. “There are great programs like ILP, or programs that provide housing for them or help them in college. But so many of them don’t know how to find those opportunities. The kids need someone to sit down with them and walk them through it.”

The County of Ventura has offered an Independent Living Program (ILP) since 1986 and provides a variety of services to youth between the ages of 16 and 21, according to their website. Amongst these services are resources for education, health, housing and transportation in addition to the Transitional Housing Placement Program designed to help independent youth find homes to live in.

One of the issues with these situations, however, is that no one can force a youth to stay in a certain living arrangement, Meshad said. For youth acting as prostitutes or involved with other illegal behaviors, it is common for them to leave for months at a time, Meshad said.

Legislation for educational opportunities

California lawmakers have also made efforts in educational legislation for foster children and youth, according to LAUSD’s report on key foster care legislation.

Former state senator Darrell Steinberg wrote Assembly Bill 490, which came into effect Jan. 1, 2004 and states that educational placements of foster care youth should always be made with the child’s interests in mind. The foster youth can remain at their original schools even if their foster care placement changes, and they should receive support in all areas of their lives — academic and nonacademic — to make their educational career as successful as possible in terms of staying enrolled and graduating, according to the report.

Kathy Dresslar, a former senate president pro tempore and Steinberg’s chief of staff in the assembly and the senate, said she staffed most of Steinberg’s foster care work in the legislature, including AB 490.

“The goal was to establish some educational baseline, some educational stability for foster youth,” Dresslar said. “You can’t just say, ‘This placement isn’t working,’ then jerk them out of school. Some of these kids were going to 30 different schools before they graduated from high school. They would move six times during the year, and none of their work would transfer.”

Dresslar said the students would not be enrolled in a new school until they had proof of their immunizations and school records. Since the social workers’ responsibilities were only to find the foster youth safe places to live, the students’ educations suffered.

“Nobody had the responsibility of making sure these kids’ educational needs were met,” Dresslar said. “It is the state’s responsibility and duty to make sure that that happens, and AB 490 is the law that reinforces that responsibility.”

Logistically, the bill makes social workers responsible for more than foster kids’ physical placement, Dresslar said. It requires them to disenroll and enroll them in schools, as well as requiring every school district to have a foster care liaison and requiring schools to give students partial credit if they did transfer between schools.

“It provides more continuity in what is arguably the only normal thing about their lives in that period of time — their school,” Dresslar said.

AB 490 has created the foundation for other foster care legislation, and has worked as a model bill for other states that have begun implementing similar legislation, Dresslar said. She said that although there is a fabric of legislation that helps foster youth transitioning out of care and the legislation has come a long way, there is still more work to do.

“It is shameful that California did not have a better way of making sure that our kids — the kids that we said their parents are too lousy to stay with, ‘We are going to be your parents instead’ — and we didn’t do anything to make sure that they transitioned from that abused, victim of a crime into a self-sufficient adult,” Dresslar said. “Things are much better, but there’s more work to be done.”

Assembly Bill 216, which came into effect in 2013, made it easier for students to transfer between schools in terms of transferred credits and coursework requirements, by lessening graduation requirements for students who transferred to a different school after already completing two years of high school. Senate Bill 578 awards foster students partial or full credit for courses already completed at a different school, according to the report.

LAUSD funds two programs — The Foster Youth Achievement Program and the Group Home Scholars Program — that attempt to assist foster youth in reaching success in school as well as setting them up for success later in life, according to LAUSD’s official website.

Jenkins said Gov. Gray Davis passed legislation that would require school districts to provide resources to English learners, low-income students and foster care students in 2014.

“We went from three counselors supporting our 7,400 foster youth to 84 counselors who support our foster youth,” Jenkins said.

The Foster Youth Achievement Program strives to provide foster children and youth in district schools with services for both academic success and health and well-being.

“We have the counselors that provide support in case management, crisis intervention, advocacy, group counseling, individual counseling and make sure that their transcripts are following them from school to school,” Jenkins said.

Jenkins said the high school counselors focus on the transition out of care as well as the students’ next steps.

“They focus on high school graduation, and LAUSD’s whole purpose is to make sure that our students are college and career ready,” Jenkins said. “If they are going to college, we make sure that they have completed the application, financial aid, scholarship application.”

The program has different goals depending on what grade the student is in, but generally, the program assesses students on their academics and works to provide students with individualized attention and planning both in academics and in other aspects of their lives, according to the Foster Youth Achievement Program executive summary.

“For counselors supporting students in middle school, they have a caseload of 75 to 85 students, and for counselors working with our high school students, they have a caseload of 55 to 75 students,” Jenkins said.

The Group Home Scholars Program strives to assist youth in group homes as well as in the transition out of group homes and into employment or further education, according to the Group Homes Program executive summary. Group Home Scholars Program has a staff that provides students with counseling, case management and advocacy, conduct academic assessments and create individual success plans.

Jenkins said while LAUSD helps foster youth take advantage of education opportunities, there is a need for more individual mentoring for foster youth.

“In LAUSD we have counselors, but their background is social work,” Jenkins said. “It might be helpful to have more staff to work with the foster youth, or more people to focus on those different areas. When you have 65 to 75 kids, you aren’t able to sit down with each kid. When I was a counselor I did that, and it took me all day. You’re helping them write their essays, because they don’t have their parents to sit down with them and do that.”

Jenkins said more funding would help foster youth in their transition out of care, because there currently aren’t enough people giving individualized help. She recommended that students be given personal coaches to help them through the transition.

“The Department of Children and Family Services has the Independent Living Program coordinators and they have one maybe two for each office and you have thousands of kids out there, so they can’t possibly provide the kids with the support they need,” Jenkins said. “They might not be able to get in touch with their ILP coordinator or won’t know who that person is.”

Lobbying

The Child Welfare League of America is a Washington, D.C. based advocacy coalition that partners with other agencies. Their goal is to help vulnerable children and youth in America. They specifically advocate for legislation that will improve the lives of transitioning foster youth, among other groups, according to their official website.

John Sciamanna, the league’s vice president of public policy, said he lobbies for a range of child welfare issues, mainly forming around the funding streams for children in foster care, children who are adopted through foster care, and children who are victims of or vulnerable to child abuse and neglect.

“We look at what the trends are and see if we can make some change in federal law, which has a big impact on the state programs in terms of foster care and child abuse,” Sciamanna said.

They try to assist states in their foster care and child abuse policies through federal funds allocated to states, which is difficult because states can elect to use the funds for wherever there are budget holes, Sciamanna said.

“There are 50 states and they have their own governments and their own funding streams, so there is some influence, but not always,” Sciamanna said.

Since his time at the Child Welfare League, Sciamanna has lobbied for policies that help transitioning youth, he said.

“Eight years ago the federal government gave states the option to extend their foster care up to age 21,” Sciamanna said. “It is a state option, and not every state has chosen to do so. We’ve been supportive of vouchers when they were created to provide funding for youth aging out of care.”

Sciamanna said the specific funding varies state to state.

“For all states, if they extend the age of foster care up to the age of 21 (or in between) the federal government will match that at the foster care rate,” Sciamanna said. “So for eligible youth, Health and Human Services would match the cost at 50 percent for a state like California. Some states like an Alabama might get a match at 70 percent of the cost.”

The nonprofit community and the federal government should coordinate the services they offer to improve the child welfare system, Sciamanna said. He said the system requires more federal funding.

“It’s part of the continuum of child welfare,” he said. “From preventing abuse to preventing foster care to supporting kids in foster care or helping them transition out, we could do a lot more. We have to do a lot more to connect these young people to college or vocational options or connect them with adults.”

While the number of children in foster care and programs to help them has gotten better over recent years, Sciamanna said there is not solid progress.

“It’s an ongoing effort,” he said. “You can make a certain level of progress, but when you back off, you will start going backward.”

Nonprofits: Promises2Kids

Promises2Kids, a San Diego-based nonprofit organization that serves more than 3,000 foster care youth, provides various opportunities and resources to those in care through their four main programs and works on a local level to help youth take advantage of available tools, according to their official website.

Rashida Elimu, supervisor of the Guardian Scholars Program at Promises2Kids, said the organization does outreach efforts to make sure they stay relevant in terms of foster care in San Diego.

“Promises2Kids has worked really hard to develop a relationship with San Diego Child Welfare Services, so through collaboration through working with them, we can get exposure to some of the students,” Elimu said. “We are educating social workers, and of course we have our ears to the ground in regard to the community of foster care youth in San Diego County, so there’s a lot of collaboration that goes on to make sure that kids are informed and the adults that work with the kids are informed about our programming.”

Elimu said many foster youth remain in care until 21 years old because of extended foster care. After 18 they become nonminor dependents of the court and the organization has programs in place to help foster care youth in transition. A non-minor dependent is a dependent of the court who is 18 years old or older and has the capacity to legally and independently make decisions. It is a voluntary status that can be terminated by the non-minor dependent at any time, Elimu said.

If foster youth decide to extend their care, they are required to maintain contact with a social worker and lawyer, which is free, and go to court every six months to ensure their eligibility, Elimu said.

“More times than not, students choose to stay in,” Elimu said. “Give them the support they need as they age and are going through school, and maintain stability during the school process. When they turn 21, they will have built the skills necessary.”

Elimu said overall, extended foster care has improved the lives of transitioning youth.

“Comparatively to before extended foster care for that age range, the statistics were much more dismal,” Elimu said. “We only have the first couple of classes that have aged out so there are limited statistics on how they are doing now, but before, 50 percent were homeless within a year and 60 percent of them were having children. They are still struggling I think, improvements have a long way to go.”

Elimu said even when foster youth decide to extend care, they may still be faced with the challenge of finding housing after they turn 21.

“Housing is not the cheapest here in San Diego,” Elimu said. “They can participate in what is called Transitional Housing Programs for Foster Care and once they turn 21 they can move into transitional housing, which is a program where they pay a significantly discounted rent.”

Elimu said they can participate in this program until 25 years old. The county implements the state and federally funded program through local agencies.

Promises2Kids’ four main programs, Polinsky Children’s Center, Camp Connect, Guardian Scholars and Foster Funds, teach skills to make life in care easier for transitioning youth, current foster care youth and former foster care youth, Elimu said. The Polinsky Center provides a diverse range of services, from a pet therapy program to a mentoring program that pairs a former and current youth to recreational services.

Camp Connect, the third Promises2Kids program, partners with the Health and Human Services Agency in San Diego and works to connect siblings separated in foster care. Foster Funds presents youth with experiences kids of the majority population might enjoy but that they would not typically be able to take part in, according to the website.

The Guardian Scholars Program encourages youth to pursue a higher degree of education. The program provides more than 100 students with scholarships for their education annually, according to the website.

“Our Guardian Scholars program serves current and former foster youth in pursuing their education,” Elimu said. “It focuses on students in the ninth grade, foster youth in high school and foster youth in college.”

Participants in the Jr. Guardian Scholars Program are exposed to possible careers in the county by touring companies and businesses, Elimu said. The Guardian Scholars Program prepares students for standardized testing, takes them on college tours and helps them with their college applications. Students can continue the program in college as well.

“With the collegiate program, we work with them until they reach their higher education goal,” Elimu said. “We offer a mentorship program so every student in San Diego County is attached to a mentor who is a community person that helps them navigate what they will do post college. They have the one person a year who will follow them through school — the same person working with you until you graduate.”

Although Promises2Kids provides foster care youth with the resources to pursue their educational goals, Elimu said they expose youth to all possible avenues.

“I don’t necessarily think it’s only education and going to school, but more has to do with exposure,” Elimu said. “We just want to expose foster youth to everything. We don’t force you to go to a four-year university, but we expose you to different careers and leave it to you to make the choices for what you want to do.”

Teen Project and Celia Center

The Teen Project is an organization whose mission is to provide transitioning foster youth who are at risk of being homeless with housing, college support, paid job internships and education for basic life skills, according to the website.

Shaema Mahdi, administrative assistant at the Teen Project, said nonprofits should be the main form of support, rather than the government, for foster youth.

“It’s our job,” Mahdi said. “They’re only going to help by giving the tools. We as a program and a nonprofit organization have the ability to educate. Legislation can only push the laws, it’s up to the organization itself to do the work.”

The Teen Project has a college home program through which they provide housing to homeless youth who have aged out of foster care. Each youth participating in the program has their own room as well as a house mom, and even resources to get a car and support services for going to college, according to the website.

Celia Center Executive Director Jeanette Yoffe speaks at conferences for foster youth, adopted youth and their parents (Photo courtesy of Jeanette Yoffe).

Celia Center Executive Director Jeanette Yoffe speaks at conferences for foster youth, adopted youth and their parents (Photo courtesy of Jeanette Yoffe).

Jeanette Yoffe, executive director of the Celia Center, an organization providing support services to foster youth and adopted youth, agreed that foster youth may be unaware of all of the federal opportunities available, and need more individual help.

“They don’t have a mentor, they don’t have someone they can call for any time of support, ‘How do I do this, how do I apply for a credit card, how do I fill out a student loan, how do I get access to community college,’” Yoffe said. “There’s some organizations that provide mentors and train them, but there aren’t enough. They need someone who can provide that ongoing support.”

The Celia Center began in April 2009, when Yoffe opened a support group in Vista Del Mar. Over the next seven years, the center started eight new support groups and hosted various conferences and workshops targeted at different subjects within the foster care population, from teenagers to parents, according to the website.

Anthony De Felicis, program director of WE LIFT LA, in his office in Tarzana (Photo by Alli Burnison).

WE LIFT LA

WE LIFT LA is an organization based out of Tarzana, California that is committed to helping transitional-age young adults build life skills and prepare to transition effectively into society. The program director, Anthony De Felicis, said WE LIFT LA comes alongside these transitioning individuals and helps provide life skills and mentoring where needed. Through the mentoring, WE LIFT LA strives to help these young adults find a vision for their lives and develop a sense of their identity.

“We build into them, we look at their strengths and weaknesses and you’d be amazed how many of them will not recall any strengths, but they will give you a laundry list of their weaknesses,” De Felicis said.

In addition to individual mentoring which focuses on career, identity, values and other formative topics, WE LIFT LA also provides life skills training, De Felicis said. For example, small group sessions are held to discuss everything from communication to manners, to resume and cover letter building. They are also trained with mock interviews, and connected with career mentors specific to their given fields of interest. These mentors differ from the life coaches in that they offer more opportunities for internships and jobs, he said.

Another service that WE LIFT LA provides is limited housing for young adults. Currently there are five women living in the house, and the program is looking to expand its housing. Housing is generally a problem for these young adults and many of them have the potential to end up homeless.

“Right now we have 7,000 former foster youth on the streets of Los Angeles,” he said.

Through this program, WE LIFT LA has seen noticeable changes in the young adults that they serve and hope to continuing growing in impact.

“We seem them dress differently, we see them having a new attitude about themselves, we see their friends change, it’s pretty exciting,” he said. “Again, each case is different and challenging but it’s great and it’s all worth it when you see that happen.”

L.A. Kitchen

In addition to many nonprofit programming efforts, some organizations work to provide hands-on help. The L.A Kitchen is located in Lincoln Heights Los Angeles, and is a nonprofit that seeks to reduce food waste and nourish and empower those in need, according to the organization’s website. In addition to food services, L.A. Kitchen has a 15-week job-training program called Empower L.A., which is targeted to prepare individuals for entry-level positions in the foodservice industry.

Zaneta J. Smith is the associate director of Clinical and Student Services at L.A. Kitchen, and works directly with the students in the program. In order to be accepted to the program, an individual must either be formerly incarcerated for 30 days or more, formerly homeless or a transitional-age foster care youth, Smith said.

The first eight weeks of the program consist of kitchen practice and various classes such as nutrition, life skills and professional development that are meant to take a holistic approach to each situation, she said. The following four weeks consist of students applying their newly learned skills through an internship. Some of these internships will then hire the students and if they are not hired they return and work with the workforce development coordinator at L.A. Kitchen, Smith said. The students then graduate from the program at the 15th week.

The admission process is relatively extensive, including interviews and a kitchen trial, and selection is assisted by a number of partnerships with social service agencies all across L.A county. The program also provides individuals with uniforms as well as books and materials.

There are a number of reasons why the food industry is fitting for a program like this, Smith said. Many restaurants do not require a background check, thus allowing a second chance for individuals who have been incarcerated, she said. Another reason is simply because food bonds people.

“Food is the universal language,” Smith said. “It is something that everyone bonds on, whether negatively or positively.”

Although some people have negative relationships with food, for others being around food reminds them of family and is celebratory in that way, Smith said. In addition to the job training, members of the program also receive counselling one day a week for 30 minutes to process their futures and emotions surrounding that transition, she said.

“Because they are young and may not have a lot of exposure to different careers, they are really not sure of what they want to do,” Smith said.

Commitment to the program is also very difficult for many of the individuals because they may not have had to commit seriously to anything in their lives before, Smith said. In addition to commitment issues, many of the individuals have an intense fear of success, because they are just unsure how to proceed with it.

One boy that went through the program continuously would self-sabotage his progress, because he had such great self-doubt due to lack of exposure.

“Just a lot of self-doubt,” she said. “Not sure if he could trust us, not sure if he could trust his mentors, here we were presenting something that he didn’t know anything about, he wasn’t used to, and it’s just a lack of trust that this will work out, because in his mind nothing had worked out up until this point. His mom died, his aunt died, his family doesn’t want him, so, he self-sabotaged.”

Through counselling and talking through some of these challenging barriers he was retained at the program, graduated and L.A. Kitchen hired him as an apprentice.

In addition to the fear of success and a high presence of self-doubt in some of these youth, the lack of general life skills can be incredibly detrimental to their success, Smith said. For example, many of these youth have never set goals before and don’t know the steps for following through on those goals, she said. Some also come without a high-school diploma or GED, and although it does not affect their participation in the program, it presents an obvious immediate setback in the working world.

One such setback, Kristofferson said, is even mentioning that you were in the system. Disclosing her status as a former foster youth can lead to discrimination, as there is still a negative stigma concerning the subject. She said most people who know her now don’t know that she was in the foster care system.

“I need a fresh start and I am the same as every other student, it doesn’t matter where you come from,” she said. “I want to be treated the same.”

Alli Burnison and Rachel Littauer completed this story in Dr. Christina Littlefield’s fall 2016 Jour 590, investigative and narrative reporting class.