False accusations of gang rape roiled the University of Virginia, leaving Rolling Stone magazine with a $3 million defamation judgement.

A Columbia University student carried a mattress with her for months to protest the university for not expelling her alleged detector.

A Stanford swimmer’s rape case went viral when his victim published on Buzzfeed a harrowing letter detailing the attack and its aftermath on her life.

These cases brought new attention to sexual assaults on college campuses.

College and university officials are attempting to meet the issue head on by ensuring legal compliance with Title IX and the Clery act, which defines and requires clear reporting on sexual assault. But they’ve also worked to foster advocacy groups on campus and increase educational campaigns to prevent sexual assault.

“There is a willingness and openness to say, ‘What is it that we need to do?’” said La Shonda Coleman, the Title IX coordinator at Pepperdine University. “‘How are we doing?’ and ‘What is it that we need to do to ensure beyond our compliance that we are approachable,’ that we’re helping. We’re working to create a safe environment. I feel schools are doing that where they are reaching out asking, ‘Can you come help us out?’”

One in five women and one in 16 men are sexually assaulted while in college and more than 90 percent of sexual assault victims on college campuses do not report the assault, according to the National Sexual Violence Research Center.

Survivors of sexual assault do not report the crime for varying reasons, according to the Maryland Coalition Against Sexual Assault. Some survivors feel the assault was not serious or important enough to report, some possess a fear of going to the police and justice system, some believe the crime will not be solved, and/or did not want their family or others to find out.

“It’s all of us who are under attack,” said Abi Smith, a Pepperdine University communication professor and debate team coach. “And we could become victims at any point.”

Smith spoke about her own experience of sexual violence during Pepperdine’s first Sexual Assault Awareness Week at the end of September.

Sexual assaults among CSU and UC schools

Within the past three years, all schools surveyed in this study reported sexual assaults on campus, including all California State University schools, University of California schools and private universities such as University of Southern California and Pepperdine University.

The Jeanne Clery Act requires universities to publish information about fire safety and all crimes on or around campus. Colleges and universities who receive federal funding must share crime information along with their efforts to improve campus safety. This information must be made publicly available through the annual security report.

Clery Act statistics come from both local law enforcement and campus officials.

“Clery is a guideline but it’s certainty not an accurate reflection of the number of sexual assaults,” said Nancy Wahlig, director of a victim’s advocacy group, Campus Advocacy Resources and Education, at the University of California at San Diego.

Collectively, the nine of the biggest universities in California, including CSU Long Beach, CSU Los Angeles, CSU Northridge, UC Berkeley, UC Los Angeles, UC San Diego, UC Santa Barbara, University of Southern California and Pepperdine University, reported 240 sexual assaults on campus from 2013 to 2015.

Prior to 2013, sex offenses fell under the categories of forcible or non-forcible. Many schools reported zero non-forcible acts, as officials deemed all instances of sexual assault as forcible acts.

Beginning in 2014, the Jeanne Clery Act expanded the definition of sex offenses within campus security reports to the categories of rape, fondling, incest, and statutory rape.

The definition of sexual assault asserts an assault occurs when there is no consent.

In many sexual assault cases, consent is blurred. The University of California provides a definition of consent that asserts consent can be revoked at any given moment and must be made clear to both parties.

Within the past three years, the CSU schools in this study reported 24 forcible sexual assaults and rapes on campus.

Within the past three years, the UC schools in this study reported 201 forcible sexual assaults and rapes on campus.

In 2013, four out of the nine aforementioned schools reported forcible sexual assaults in the double digits. In 2014, reported rapes remained in the double digits at UCLA with 26 reported rapes. The next highest was UCSB with 11 reported rapes and USC with seven reported rapes.

With the exceptions of UC Berkeley, CSU Northridge, and CSU Long Beach, there has been a decrease in the amount of rapes reported over the past three years.

“I’m really excited to see the attention that this topic is getting, the support it gets from students, staff and administration,” said Hannah DeWalt, Pepperdine University’s Step Up Health and Wellness Education coordinator. “We have great resources to use in this area and we have some momentum. I hope to see that continue because one is too many.”

The Jeanne Clery Act

Beyond reporting crimes, the Clery Act also mandates that institutions must provide survivors of sexual assault, dating violence, domestic violence and stalking with support including making academic, transportation, living or work-place changes to help them cope and providing assistance in notifying local law enforcement.

Annual campus safety reports equip survivors with resources and procedures to deal with sexual assault, domestic violence or stalking. Safety reports advise survivors to preserve evidence of the assault, seek medical help and emotional support, and contact authorities including campus safety and local police.

President Barack Obama signed a bill in 2013 that strengthened the Violence Against Women Act, which included amendments to the Clery Act that outlined additional rights to survivors of sexual assault.

The Clery Act as well as the Department of Education holds colleges and universities accountable for following and implementing the provided definitions.

“The enforcement is the Department of Education because it holds them accountable by using plain language that people can understand,” Abigail Boyer, a member of the Clery Center, said. “Institutions have to use the same definitions.”

The Clery Center is a nonprofit organization that works with colleges and universities to create safer campuses. In doing so, the Clery Center provides an overview of the Clery Act, offers resources for advocacy and training nationally.

“We host trainings throughout the country and those remain open for anyone in institutions who would like to attend,” Boyer said. “One of our goals is to make sure our training is accessible.”

The Center is preventing and responding to sexual assault, Boyer said.

“It can’t just be on the shoulders on one individual,” Boyer said. “We try to highlight working collaboratively. Everyone plays a role in campus safety.”

The Clery Center and Clery Act implemented the requirement that institutions lay out the the options available for survivors on how to respond to the assault.

“When a survivor comes forward on campus they are given something tangible,” Boyer said.

“Options are available so they can decide which option is best for them. Every survivor is different. The goal is to make sure individuals who come forward know their options in a thoughtful way.”

The Clery Center is proud of the ongoing work that is being done to combat the issue of sexual assault, Boyer said.

“We’ve seen a lot of incredible work in both prevention and response,” Boyer said. “One of the things we’ve learned is there is always more we can do. How do we make training accessible and how are we able to build resources? If one person leaves the institution there are still policies in place.”

Title IX

One of the most important policies pertaining to sexual assault on campus is Title IX, which states, “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.”

Title IX is responsible for college and university compliance with state and federal laws revolving around sexual misconduct, sexual assault, interpersonal violence, stalking and other harassment complaints. The law administers mandatory trainings for students and employees and provides numerous educational opportunities to campus communities to raise awareness and prevention.

“All of our hands are in it and we’re working as best as we can to create safety,” Coleman said.

Coleman said how grateful and impressed she is by the amount of people committed to the work.

Prior to becoming Pepperdine University’s Title IX Coordinator, Coleman worked for the UCLA Rape Treatment Center as director of College Programs for about 10 years.

“Before I was officially working as a clinician, as a first responder at crisis intervention at the Rape Treatment Center, I worked with survivors,” Coleman said. “I had worked with survivors as a peer; I worked with survivors as a friend. This issue is so pervasive that it already been a part of my life long before I had a title that said, ‘Go to La Shonda if you’ve been sexually assaulted, she can help you.’”

Her title at the UCLA Rape Treatment Center involved working with a number of colleges to address the issue of sexual violence. Coleman worked on the response for survivors, helped local law enforcement to understand the issue from a trauma approach and how to interview survivors, worked on the adjudication process on campuses and worked directly with students.

“I feel that it’s important for us to stay responsive to the communities Title IX is designed to protect and that’s humanity,” Coleman said. “I do not believe that we can say OK, this is what Title IX is today and we stop here. No, we must constantly be responsive to the needs of the community and so if we stay in that way of being intentional about being responsive then we have this opportunity for it to constantly evolve into what it needs to be to protect students on campus.”

Coleman’s work also involved directly working with survivors of sexual assault.

“I worked directly with students, which is incredibly important with this work.” Coleman said. “Just hearing their experiences and making sure to communicate that back to the first responders on campus so that there was a collaborative effort in addressing it.”

Coleman said that a first responder to a sexual assault disclosure also goes through a form of trauma.

“There’s this secondary trauma that happens for anyone who witnesses human suffering,” Coleman said. “There’s the impact that it has on the provider, the clinician, the advocate, the Title IX Coordinator, the case manager, the professor who is the first person to receive that disclosure. There’s that secondary impact of witnessing that suffering even in just the narrative.”

That secondary trauma translates to a heaviness that Coleman experiences with every survivor she works with, she said.

“I sense in my heart a heaviness right now,” Coleman said, “and that I know what the witnessing of that pain is like and though I can’t hold that pain because it’s theirs, just to hold the space for them I know what that’s like. Every time is it’s own new thing.”

Despite the ongoing heaviness, Coleman enables it to motivate her and continue serving in her work.

“So the heaviness is not the trauma, it’s that person’s life and the value of that person’s life that I feel that I’m holding,” Coleman said. “The value of human life is so important and the injury to that is equally important and that motivates me to say there’s meaning and purpose to my life.”

When a student comes forward they are identified based on Title IX’s policy as the complainant and the person that is alleged to commit the assault is the respondent, Coleman said.

“My role is to ensure a fundamental fairness for both parties through this process of reporting,” Coleman said.

Within Title IX’s policy, it is not required that a student file a formal complaint in order to receive accommodations, Coleman said. Accommodations may include rescheduling tests students may miss due to the trauma, connecting them with Disability Student Services depending on the impact of the trauma, or relocating the student’s housing, Coleman said.

“This entire approach I believe is a huge investment saying we are absolutely committed to doing this in a responsive way,” Coleman said. “We want to be compliant but we want to go beyond that and really engage with the community so they’re heard and respond accordingly.”

An important component to Coleman’s position is informing the complainant and respondent of their rights and options. Coleman outlines the actions a complainant can take if he or she wishes to file a report.

“My hope and my intention is that by giving the student all of the information about their rights and options that if they decide to report that they understand that process and know what support is in place so they can navigate that in a way that’s meaningful to them that feels supportive to them,” Coleman said.

Coleman said she is willing to speak to the complainant about his or her rights and options on multiple occasions.

“I may need to talk to them a second time, a third time, a fourth time and that’s OK,” Coleman said. “I welcome that.”

Coleman said in the initial conversation she explains to the student that her door is always open and lets the student know how to reach her assistant. Lauren Herzog, the case manager for Student Affairs at Pepperdine University, assists Coleman with survivors by providing services and accommodations for what they need.

“They don’t have to be ashamed of anything,” Coleman said. “If they need that information several times it’s OK we’ll give it several times. Same with the respondent, if they need information several times they’ll have it several times. And hopefully that can empower them to fully engage in any option that’s meaningful to them, that’s my hope.”

Campus responses

Many campuses implemented the “It’s on Us” campaign to open up the conversation about sexual assault. The campaign educates college students about sexual assault and trains them on how to prevent sexual assault as a bystander.

“One of the best practices in sexual assault prevention education is bystander intervention training,” DeWalt said.

Bystander intervention helps students identify scenarios where sexual assault might occur, DeWalt said.

California law also requires all faculty and staff to take online training about sexual violence as well. Although it is a useful measure for faculty and staff to be informed about sexual violence, the training is only conducted at the beginning of the academic year.

“We once a year we have to hop on the computer to talk about sexual violence,” Smith said. “I think it needs to be integrated into our ongoing conversation about safety.”

UC and CSU schools offer a program called CARE, Campus Advocacy Resources and Education. The program started from a grant from the UC system and began in 1978 at UCSB as the Rape Prevention Education Program. The program altered its name in 2012-2013 because the original name was not intuitive to all that the program offered, said Briana Conway, the acting director of CARE at UCSB.

Advocates of the program assist students who have experienced sexual assault, dating or domestic violence, stalking, or have questions surrounding sexual violence. CARE provides confidential assistance, advise on campus, legal, medical, judicial, emotional and academic resources. Advocates help to schedule necessary appointments and accompany victims to meetings, appointments, forensic examinations, and in speaking with friends and family. CARE also helps survivors explore options for reporting and next steps, according to CARE’s website.

“I think we’ve done a good job but we can do a better job,” said Wahlig, the UCSB CARE director. “I’m always concerned that there are survivors who are struggling and not aware that we are a confidential service. They can trust us and there’s healing and recovery after a significant trauma. I’ve worked with so many survivors who’ve recognized they don’t have to keep it a secret.”

The confidentiality component to CARE helps survivors seek help while remaining anonymous.

“Knowing that most sexual assaults go unreported, our prevention efforts are strong,” Wahlig said.

CARE advocates and friends of survivors are trained to respond directly to disclosures.

“We say to them, you may be overwhelmed to hear this,” Wahlig said. “First of all, believe your friend, people don’t make up these stories. Let your friend make the decisions on what they want to do, let them know our resource is available 24/7.”

Survivors can call CARE’s hotline, which is open and available 24/7.

“Survivors are taking the initiative far more than ever before,” said Briana Conway, acting director of CARE at University of California at Santa Barbara. “I think there’s a cultural shift in reducing sexual violence stigma. I think this generation of students is more empowered. We’ve reduced the stigma of getting help is not something to be ashamed of. They’re entitled to these resources and they’re here to serve them.”

The prevention efforts and training that CARE offers takes on many forms.

“We don’t necessarily know how to measure prevention,” Conway said. “The more education and outreach we do the more survivors come forward. I think we’re building awareness, but ultimately our office over the last five years has really allocated its resources to serving survivors.”

Wahlig said prevention efforts begin by enforcing that all incoming students complete the university’s online course. CARE designed the course to educate students on sexual assault prevention, bystander intervention and defining consent.

“If they don’t complete the course, they receive a letter from the college dean,” Wahlig said. “If they don’t complete it later, they have to meet with the College Dean. We have a 99 percent completion rate.”

At Pepperdine University, all incoming students have to take an online training called “Think About It,” which allows students to engage with scenarios, and instructs students on the on- and off-campus resources available to them such as confidential counseling services, medical exam facilities, other crisis intervention resources, and gives suggestions on how to best support someone who has experienced sexual, dating or domestic violence, or stalking.

Orientation for incoming students also includes peer-led training to reinforce the training on consent and bystander prevention, Wahlig said.

“It’s more of a performance so they’re demonstrating what can be done,” Wahlig said.

CARE does additional prevention training with groups on campus such as Greek life and Athletics.

During training, CARE leaders walk students through possible scenarios where sexual assaults could occur and be prevented, Wahlig said. They teach students an acronym for preventing asaults, IDEAS, which stands for interrupt, distract, engage peers, authorities and safety.

In these situations, the authorities do not always mean police, Wahlig said. Certain scenarios call for different authoritative figures, such as the host of a party, a senior student, or possibly an employee at the location.

One scenario CARE presents is being at a party where people are drinking and someone goes into a bedroom. This situation can lead to someone else entering the room and creating a situation where sexual assault could occur.

“It’s simple scenarios,” Wahlig said. “Because that’s the reality.”

Other advocacy groups

April 2016 marked the 20th anniversary for The Clothesline Display at UCLA. The Bruins Consent Coalition hung up shirts around campus for survivors of sexual violence to write on or otherwise represent their experiences on the shirts. Students used multiple colors to represent the different forms of violence. The three-day event fostered a space for healing, comfort and support.

“We, the co-directors of Bruin Consent Coalition, implore you to experience the Clothesline Display — to read the shirts and to recognize these survivors’ stories as truths,” Ishani Patel and Chrissy Keenan wrote in “20 Years of Solidarity: The Clothesline Display at UCLA” on the Bruins Consent Coalition site. “We challenge you to embrace the feeling of being comfortably uncomfortable at the Clothesline Display. It is an incredibly emotional and heavy event, but it is beautiful in the raw, unapologetic realities it expresses.”

Pepperdine University hosted a similar event at the end of September this year. The Clothespin Project allowed students who are survivors of sexual assault or friends of survivors to decorate shirts. The idea went along with airing the “dirty laundry,” DeWalt told the Pepperdine Graphic.

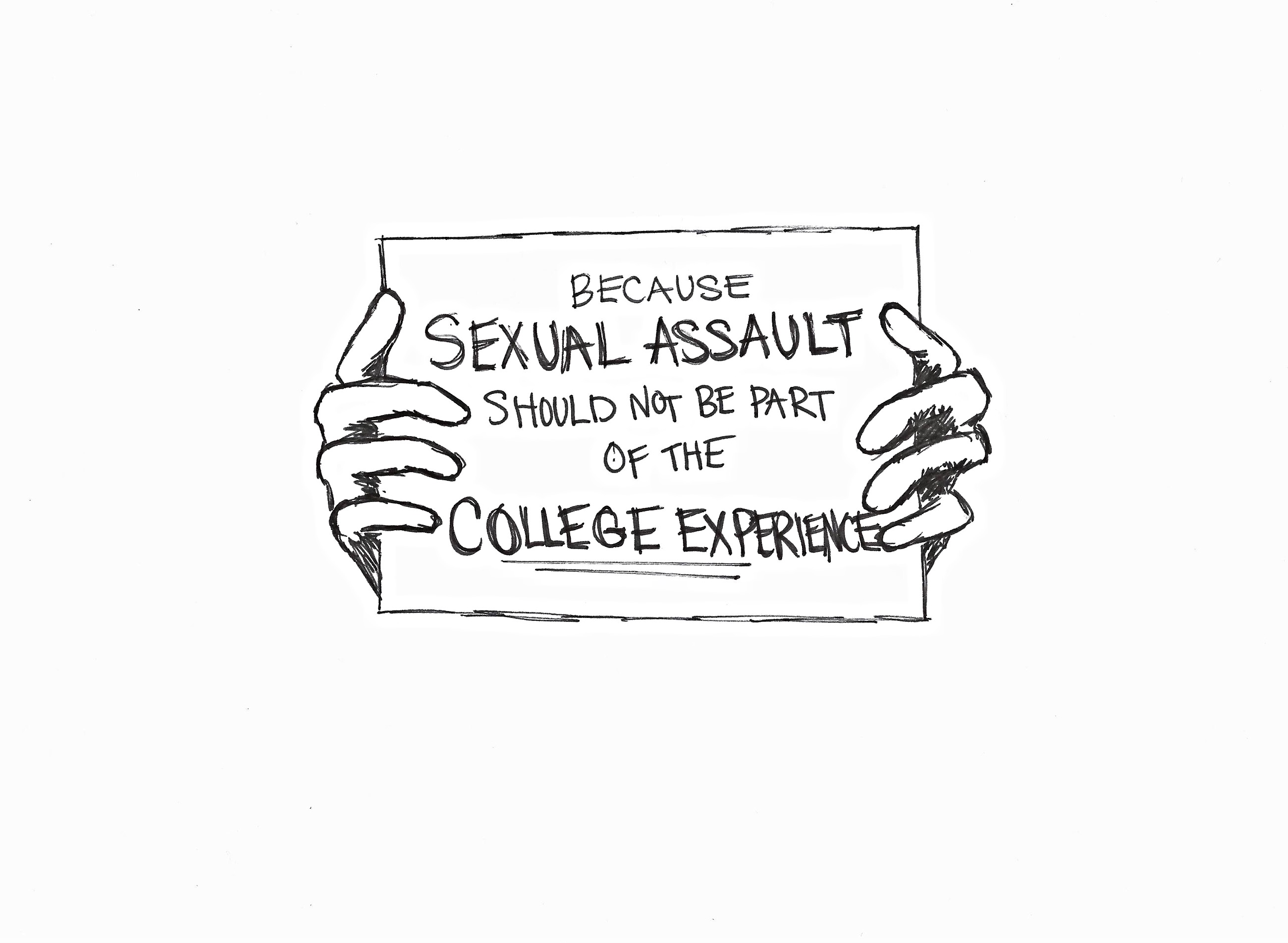

Illustration by Caroline Laganas

Other advocacy groups that males lead across campuses are Men Can Stop Rape and Men of Strength at UCSB. Both advocacy groups examine the role of masculinity and how that influences sexual assault, according to both advocacy groups’ websites.

The Campus Men of Strength (MOST) Club is a college-level program with chapters at colleges and universities across the United States. Campus MOST clubs are for students dedicated to actively engaging men on their college campuses to prevent domestic violence, sexual violence and other forms of men’s violence against women. Members examine and challenge masculinity as it relates to themselves and society, rejecting harmful aspects of traditional masculinity in favor of individual masculinities that affirm their unique realities and experiences.

Rape Aggression Defense training is a program California State University at Long Beach offers and the program is available across the United States and Canada. RAD offers self-defense training. The program “begins with awareness, prevention, risk, reduction and avoidance, while progressing on to the basics of hands-on self defense training,” according to RAD’s website.

The Office for the Prevention of Harassment and Discrimination (OPHD) at UCSD offers a program called, “Sex in the Cinema.” The program began in 2002 and sponsors free screenings of films that have storylines relating to sex and/or gender issues, according to the program’s official website.

OPHD officials pose questions to the audience prior to the film to increase awareness of bias, and explore cinematic depictions of harassment and discrimination, according to the website. The films include a variety of genres, from comedies to action/adventure to documentaries.

Some of the films OPHD has screened are“To Kill a Mockingbird,” “Bridesmaids,” “The Hangover,” “Love Actually,” and “Captain America: Civil War.”

SAFER is a nonprofit organization that provides college students with the resources they need to build successful grassroots campaigns, according to SAFER’s official website. Columbia University students began SAFER in 2000. Since then, the organization strengthens student-led movements to combat sexual and interpersonal violence on campus, according to the website.

“As an advocate, it’s important to provide that sense of agency for them because that helps to make them feel empowered, to have a sense of control, so that’s always important,” Coleman said.

Caroline Laganas completed this story in Dr. Christina Littlefield’s fall 2016 Jour 590, investigative and narrative reporting class.