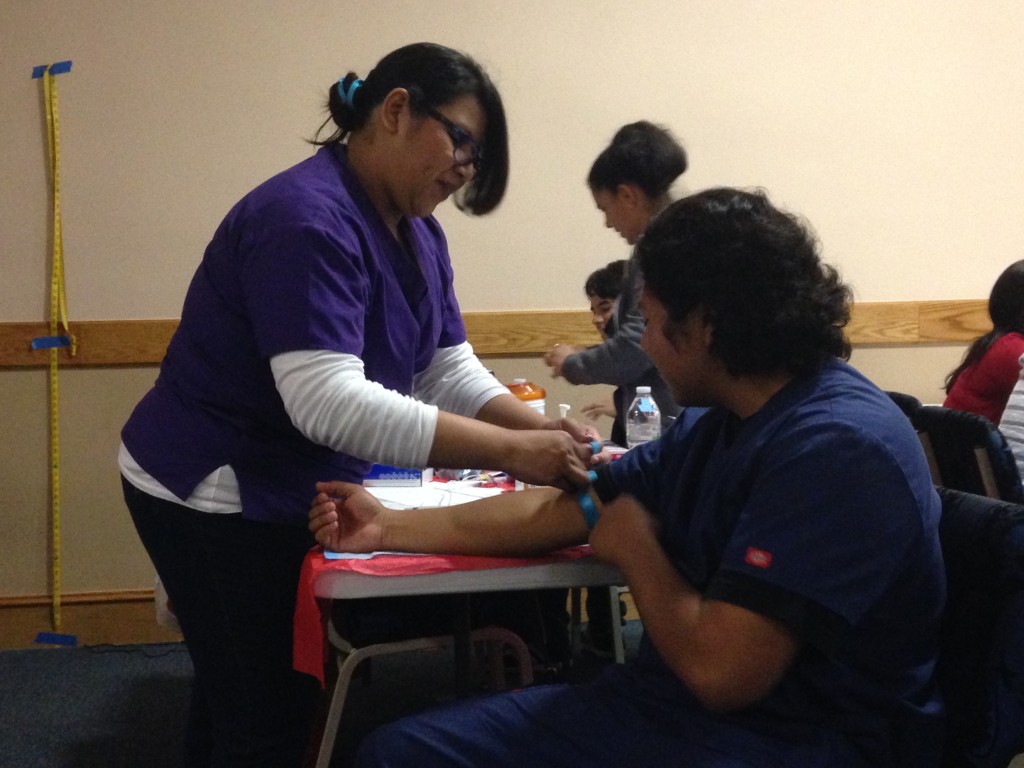

Every year, a daughter waits to bring her aging mother to the sanctuary of a little church in Reseda, California, so she can have annual testing done — a bone density exam, blood glucose testing, an eye exam and a pap smear.

This is the only form of assured healthcare for the elderly woman and her family. The only way to get preventative testing. If any tests come back positive, she will at least have some documentation to show a doctor, if she can find one to treat her.

The daughter, Isabel, and her mother spent an entire Saturday morning shuffling in between scurrying children, babies clinging to their mothers, and others sitting with tightly drawn brows, twiddling their tense hands as they waited for their turn.

While Isabel was willing to share her first name, she was not willing to share her mother’s name or family name due to their undocumented status.

Ivan Martinez, a registered nurse volunteering at the clinics with the National Kidney Foundation, said many uninsured people will come to the biweekly clinics so they can obtain something substantial to show a physician. Those without insurance have difficulty even getting preventative tests done, but doctors are more likely to listen once the problem is officially diagnosed. Thirty-six churches take turns hosting the clinics, usually one each year.

Martinez’s work in emergency rooms in Los Angeles County and the University of Southern California Medical Center has led him to believe that not enough is being done for the undocumented patients.

“In working in the emergency department I see people getting dialysis and I think, ‘They could have prevented this. You should not be in this stage.’ Then I ask, ‘Who is failing the patients?’ ”

…

For those who don’t have the benefits of insurance, receiving appropriate health care is a daunting need. Many Los Angelenos turn to emergency rooms, minute clinics, church-run charity programs, non-profit organizations and urgent care centers when they need care.

That need is magnified for immigrants, many of whom do not have access to state programs like Medi-Cal or the Affordable Care Act, work jobs that do not offer health insurance, and must pay higher out-of-pocket costs for the care they receive. For undocumented immigrants, the fear of getting deported gets added to the fear of paying the bill.

The United States serves as residence to roughly 11.2 million undocumented immigrants, according to PEW Research Center. In California, the number of undocumented immigrants is the highest in the country, with more than 2.4 million undocumented residents. The next highest state is Texas with 1.6 million undocumented residents.

Many immigrants, particularly undocumented immigrants, often work in more dangerous industries than U.S. citizens, and do significant amounts of manual labor, adding to their need for health care. The typical industries immigrants work in – agriculture, food service and construction – tend to have low health insurance coverage, according to Healthcare.gov.

Though their risk for injury is higher, many of these 11.2 million undocumented immigrants are afraid to ask for treatment, fearing deportation and being turned away from clinics and hospitals. Whereas there are some government programs to help, such as the Limited Scope sector of Medi-Cal and the newly developed My Health LA, navigating those programs requires both engaging with government officials and providing proof of income.

***

The older woman moves slowly from one folding table to another, gazing over the vast array of instruments on the table as she made small talk with the different volunteers. Many representatives from hospitals and national healthcare associations are present, including the National Kidney Foundation, University of California, Los Angeles Olive View Hospital, Northridge Medical and Providence Hospital, just to name a few.

Isabel’s mother has been lucky — no major health issues. Isabel said it’s easier for her to bring her mother here than to try and make an appointment elsewhere.

“One of the problems I always have is that it takes more than a month to make an appointment when my daughter or mother could need treatment right away. Emergency rooms cannot do much — they just send us home,” Isabel said.

***

Hospital and clinic officials in the Ventura and Los Angeles county indicated an unspoken “don’t ask, don’t tell” system when treating immigrants.

“You know, most of the patients we see use a fake address for their contact information because they don’t want to give their real information,” said Dr. Jalal Dufani, a second-year resident at UCLA Olive View Hospital in Sylmar. “Like they will give the phone number or address to Pizza Hut.”

Dufani said he has had to communicate with the son or daughter of a patient who claim that the parent has “returned home to Mexico.” After explaining that he is only trying to help his patients, and make sure they return for a follow-up appointment, the child would say that the parent was actually in the kitchen and would be right on the phone.

Medical professionals confirmed they see immigrants in their emergency rooms and urgent care centers, from Ventura County Medical Center to St. Joseph’s Hospital in Santa Monica to UCLA Olive View.

However, most medical facilities do not track how many immigrants they see, in part for fear of scaring undocumented immigrants away from seeking care in the first place. But they also simply do not track patients based on immigration status.

“We don’t and cannot track based on immigration status,” Sheila Murphy, spokeswoman of Ventura County Medical Center, said.

Murphy said those immigrants who can qualify for MediCal benefits, such as those who have residency or green cards, are processed by the California Health Services Agency, and her hospital would not know the applicant’s status. Undocumented patients just go into self-pay.

“We do not ask immigration status to provide care,” Murphy said.

Los Angeles County officials were able to pull numbers on how many patients accessed a few government programs designed for immigrant patients. Out of 568,237 unique patients to county medical facilities, 10,185 patients had Limited Scope Medi-Cal in the July 2013 to June 2014 fiscal year.

Limited Scope Medi-Cal is for undocumented immigrants. It provides care for pregnant women and limited emergency care to other immigrants, said Anita D. Lee, the principal deputy county counsel from the Public Service Division of LA County.

As per the name, what care gets covered for non-pregnant patients is limited to strictly emergencies, Lee said. For instance, a heart attack is covered only until the person is stabilized and sent home, so after care isn’t covered. A broken leg is covered, but not having the cast removed.

Another 1,011 patients qualified for assistance under Section 1011, a federal program to reimburse medical providers for emergency care given to undocumented immigrants. About 103 patients qualified for both this program and Medi-Cal, Lee said.

According to Lee, these numbers only reflect the expected payee or source of pay for the patient, and may not be exact.

The county also operates an ability to pay program, which allows patients to negotiate bills based on income, up to 400 percent of the federal poverty level, Lee said. That’s up to $47,080 for a single person up to $97,000 for a family of four. This program does ask where a patient is born, as it is not meant to be for temporary visitors. It is open to undocumented immigrants. Individuals apply only after they are billed.

“Some may be immigrants but don’t apply for help, they may just pay the bill, others may never pay the bill and it ends up going to creditors, and you may never know it was an immigration status issue,” Lee said. “So there is a lot of ambiguity and a lack of real hard numbers in the undocumented category. There are people who are simply poor who need (the ability to pay program).”

LA County also funds My Health LA, a new program started in 2014 designed to help low-income Angelenos, including undocumented immigrants, get access to health care. Whereas the Affordable Care Act has expanded access to health insurance for many citizens, immigrants generally cannot receive federal subsidies to purchase health care.

The program provides primary care, health care advice and other health care services to individuals without health insurance who live in Los Angeles County with an income at or below 138 percent of the federal poverty level.

Jan Emerson-Shea, vice president of External Affairs of the California Hospital Association, said California hospitals lose $14 billion a year on uncompensated care, and roughly 10 percent, or $1.4 billion, of those losses may be from undocumented immigrants.

“It is absolutely a guestimate,” Emerson-Shea said, and one the federal government uses too.

Anyone who comes to a hospital for emergency care receives it, Emerson-Shea said. There are five different “buckets” where California hospitals lose money for uncompensated care, Emerson-Shea said. The two biggest are the shortfall between Medicare and Medi-Cal payments and what the medical care provided actually costs. Next is the shortfall between money the counties provide hospitals to care for the uninsured or underinsured and the cost of care. Hospitals also offer charity care to help patients who cannot pay, which is always based on the patient’s income. Finally, hospitals write off bad debt from patients who did not pay their bills but never sought to negotiate the bill or get charity help.

Southern California suffers the heaviest losses for uncompensated care.

“Los Angeles County has the largest amount of undocumented in the state,” Emerson-Shea said, “San Diego and Imperial County have a lot as well.”

Patricia Aidem, spokeswoman for the California region of St. Joseph’s Hospital, said many of their repeat patients who come into the emergency room who don’t have insurance are quietly asked if they would like to be connected with a charity organization or My Health LA.

Providence Health and Services of Southern California, which is a not-for-profit Catholic health care ministry, also provides assistance to undocumented immigrants, said Connie Cruz, the director of Health Ministry and Clinical Programs at the Providence Center for Community Health Improvement.

Providence provides health care to undocumented immigrants in three predominant ways: charity care, Medi-Cal, and community outreach programs such as Access to Care, the Mobile Health Program, the Kids Care Van in the South Bay, the Vaseck Polak Clinic in the South Bay, the Health Insurance Enrollment Project in the South Bay and free health fairs like the one Isabel and her mother visited in Reseda.

Cruz wrote in an email that the most common ailments seen in the uninsured at Providence are related to chronic disease such as diabetes and the complications from diabetes (e.g. circulatory issues, kidney disease, etc.), hypertension and conditions related to hypertension, heart disease, and respiratory related diseases.

“Many conditions treated through our emergency departments were illnesses that could have been treated in non-emergent settings, but because patients had limited access or no medical home they seek care in the E.D (emergency department),” Cruz wrote.

She also added that Providence served more than 6,000 patients under the umbrella of charity care at a cost of $31.2 million in 2014. They saw more than 68,000 patients through Medi-Cal that year and covered $107 million in bills for Medi-Cal patients unable to pay for their services.

CVS Minute Clinics are another source of health care for those without insurance. In visiting several Minute Clinics within the Los Angeles area, it is apparent that cheaper prices are offered for basic care, which can be paid for with cash, checks or credit cards.

These clinics offer services like minor illness and injury exams, skin conditions exams, wellness and physical exams, health condition monitoring and vaccinations.

Even for those immigrants with access to Medi-Cal or Medicaid, finding a doctor who will take the coverage is tough.

Sean Wherley, who is head of Media Relations for the the Service Employees International Union United Healthcare Workers West division (SEIU-UHW) said the union is committed to ending the healthcare inequality in California.

“We can accomplish our goals by raising the Medi-Cal reimbursement rates, which in turn will encourage more doctors to see Medi-Cal patients and thus eliminate the difficulties such patients experience like longer wait times and driving farther to find a doctor,” Wherley said.

Whereas undocumented immigrants only have access to Medi-Cal Limited Scope or programs such as My Health LA, documented immigrants in California can receive access to state-subsidized care such as Medi-Cal.

That may change if courts allow President Barack Obama’s executive order, which would allow certain undocumented immigrants to gain temporary legal status in the United States, to move forward. Courts stayed the order, which was supposed to take effect in February, after 26 states sued.

By shifting more undocumented immigrants into the documented category, the executive order will mean more immigrants will be able to qualify for Medi-Cal in California.

The executive order, which Obama issued in November 2014, has two key components. It would offer a legal reprieve to the undocumented parents of U.S. citizens and permanent residents who’ve resided in the country for at least five years. This would remove the constant threat of deportation, which affects California particularly, since the state is home to 23 percent of the nation’s entire undocumented immigrant population, according to The Public Policy Institute of California.

It would also expand the 2012 Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program that allowed young immigrants under 30 years old who arrived as children to apply for a deportation deferral and gain legal status. The executive order allows immigrants older than 30 to qualify.

California State Senator Ricardo Lara, a Democrat for the 33rd district, reintroduced legislation in December to allow all Californians, documented or not, to apply for Medi-Cal or buy insurance on the public exchanges. It passed the Senate’s health committee and is now being considered by the appropriations committee, Lara spokesperson Jesse Melgar wrote in an email.

While the executive order is in legal limbo, immigrants seek care through a myriad of public and private services.

…

Nonprofits are often a welcome source of non-threatening aid for immigrants in need.

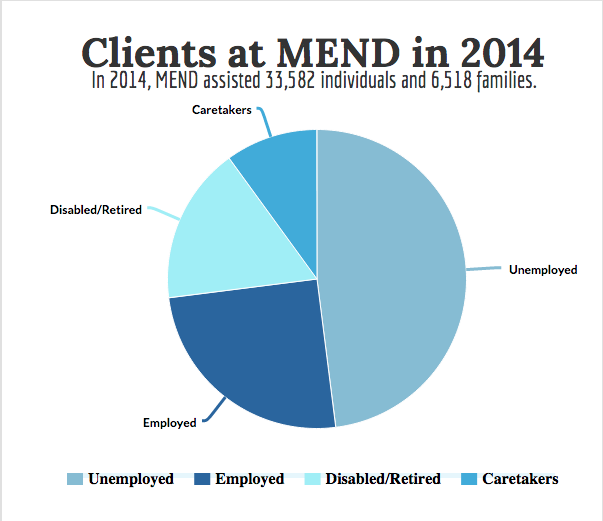

MEND, or Meeting Each Need with Dignity, is a non-profit in Pacoima, California, and their official mission is to “break the bonds of poverty by providing basic human needs and a pathway to self-reliance.” MEND provided assistance to 33,582 individuals and 6,518 families in 2014, according to the annual report.

On average, MEND sees roughly 37,000 clients in a single month, 48 percent of which are unemployed, 25 percent who are employed, 17 percent are disabled or retired and 10 percent are caretakers.

Of these individuals, 55 percent were born in the United States, 31 percent were born in Mexico, 9 percent were born in Central America and 1 percent were born in Asia, the Pacific Islands and South America.

According to MEND, 60 percent of the individuals assisted at the center do not have high school diplomas, and 37 percent do not have health insurance.

“We treat those who do not have health insurance and are at or below 120 percent of the federal poverty level,” said Victor Estrada, medical clinic manager at MEND.

Estrada said their medical clinic is made up of three components: primary care, health education and eye care. They ask clients to give a $12 donation to see a primary care physician, but Estrada made it clear that this is not required. The physicians are volunteers from Kaiser Permanente, Providence and other surrounding hospitals.

Nine volunteer optometrists give comprehensive eye exams and eyewear as part of the eyecare program. MEND asks patients to donate $20 toward the cost of their glasses if they can.

The Health Education program is focused on preventative education, such as how to manage diabetes and maintain a healthy weight. Estrada said two out of every three patients they see at MEND has some type of diabetes or hypertension — high blood pressure. Hyperlipidemia — high cholesterol, is the third most common disease they see.

Costly and damaging to both the individual and the nation, each of these diseases are preventable, or if treated by medication, manageable.

“We want to make sure we have enough money to cover each new patient,” Estrada said.

For emergency services, MEND will send its patients to nearby county hospitals like Olive View, where Dufani practices.

“It doesn’t matter who they are, we give them treatment at Olive View,” said Dufani, who believes more needs to be done to help immigrants access care.

Olive View and MEND also collaborate on research for the Center for Disease Control, including research on Chagas, a life-threatening disease that occurs when individuals come into contact with the feces of a parasite known as Trypanosoma cruzi.

Dufani said he has been working with Dr. Salvador Hernandez to research the Chagas disease, prevalent among Hispanic people, over the last three years. Chagas is a disease that slowly enlarges vital organs and with time is gruesomely fatal. If caught early, it is easy to treat.

Olive View’s volunteer efforts, with help from doctors like Dufani and Hernandez, have furthered Chagas studies and saved the lives of many left without health care across Los Angeles.

…

Both the county and the nonprofits, however, have limited resources to provide healthcare services.

“Right now, the medical department isn’t taking new clients,” MEND’s Client Intake Coordinator Gabriela Olea said. “We don’t have enough funds, for our diabetic clients alone we have almost 30,000 clients.”

The nonprofit’s resources are consumed by clients faster than the volunteer’s hands can move.

Both undocumented and homeless residents within the area of the northeast San Fernando Valley are able to turn to MEND for their basic needs.

Olea said that only seven out of the nine cities in the valley are currently supplied with medical assistance, since all of the center’s medical costs are very high.

***

Most county hospitals like Olive View and charity-focused hospitals like Providence Health and St. Joseph’s focus on underserved communities — the undocumented and the uninsured — by supporting free health clinics throughout the year.

The biweekly health fair is one way hospitals and health associations help, with the aid of 36 churches who take turns hosting. These church clinics treat roughly 200-300 patients twice a month — or 4,800 to 7,200 patients annually.

They provide services like cholesterol and blood glucose testing, weight management guides, blood pressure testing, mammograms, bone density exams and eye exams.

Even with all the services these health fairs provide, it is very difficult to spread the word to the entire undocumented population that they exist. And even if they could broadcast their services, the health fairs would not have enough resources to provide testing for the estimated 762,000 undocumented persons in Los Angeles County, according to Martinez and the Los Angeles Almanac.

The concept of providing sanctuary is not new, but it certainly isn’t outdated in the 21st century either. Many undocumented immigrants seek security and medical hope within the walls of the 36 church clinics around Southern California, as well as with programs like MEND, My Health LA, emergency rooms and minute clinics.

For people like Isabel and her family, health is a treasured gift not taken for granted.